Was Scotland's Darien colony doomed to fail?

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

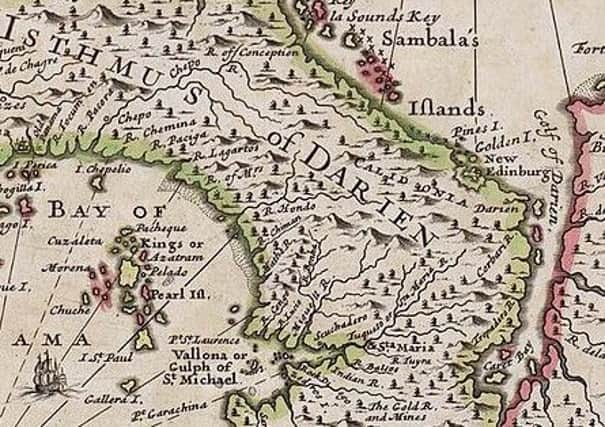

The ill-fated venture was a disaster. It cost the lives of around 2,000 Scots who had sailed to Central America in 1688 and 1699 to build a trading hub that would straddle two oceans. But the colonists had not prepared for the mosquito-infested jungles that awaited them on the arid spit of land the Scots named, New Caledonia.

The failure of the colony left Scotland in financial ruin. Scots had poured £400,000 into the project in the 1600s which historians have estimated is close to £100billion in today’s money - about half the available national capital of the time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis enormous loss played a major part in ensuring the eventual union with England in 1707. Could history have played out differently or was Darien doomed to fail?

Caledonia’s demise

While mismanagement and poor preparation are certainly to blame for Caledonia’s fall, there were many barriers obstructing the fledgling colony’s success.

“Darien was always going to fail,” says historian and author John McKendrick.

He continued: “The Scots placed their colony at the most critical juncture in Spanish territory.

“By the late seventeenth century the Spanish Empire was in decline but it was still a very powerful world power which ruled from northern Mexico to the tip of Argentina.

“Spain was a self-contained empire it did not trade with other powers.”

The Spanish did not need to trade with outsiders, they extracted huge amounts of wealth from the native peoples of Central and South America to fund their empire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Scots picked the worst place. It was in the heart of Spanish territory. It was the equivalent of the Russians having a military base 100 miles from Washington DC.

“The Spanish were simply never going to allow it.”

The Scottish stubbornly refused to abandon their colonial dream even as their numbers dwindled from disease and ships carrying fresh supplies failed to arrive. Upon hearing of Spanish intentions to launch a direct attack, the starving Scots launched a pre-emptive strike on the nearby Spanish fort. The Spanish retaliated and defeated the beleaguered colonists who were forced to leave Darien for the last time in April 1700.

Despite Spanish aggression, many Scots at the time blamed the failure of the Darien dream on the English, “Then England for its treachery should mourn”, declares an eighteenth century Scots ballad.

At the time England’s colonies in the West Indies and North America were expressly forbidden to communicate and trade with the Scottish outpost. The Auld Enemy’s refusal to support the Scots was linked to foreign policy and England’s desire to remain allied with Spain.

England’s Dutch ruler at the time, King William III, was determined to protect his homeland from France and the Spanish were central to ensuring its protection.

McKendrick explains: “Dutch King William III made it a priority to protect the Netherlands from French invasion.

“To do this he needed to keep Spain and her huge navy on side.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut William was not just the king of England. Since the Union of the Crowns in 1603, Scotland and England had shared the same monarch. By refusing to support the Darien venture, William was denying aid to his own subjects.

Union from the ashes

In the seventeenth century Scotland was in dire straits. Scots merchants were excluded from England’s rich overseas trade, poverty was rife and a series of bad harvests killed around a third of the population in the 1690s. The Darien disaster, in which around one-quarter of Scotland’s total wealth was lost, compounded Scottish woes.

But the loss of Darien left Scotland with more than just empty pockets says McKendrick.

He said: “Darien had a profound psychological effect on Scotland. It robbed the country of confidence.

“It was a loss that would have been felt by everyone. Every Scot at the time would likely have known someone lost or known someone who lost money investing in the colony.”

Consequently Scotland’s landowners and influential citizens - many of whom would have been Darien shareholders - supported the Union of Parliaments in 1707, which provided a payment of £398,000 (a sum known as ‘the Equivalent’) as compensation for the Darien losses and provided much needed aid to the Scottish economy.

McKendrick added: “The union was salvation which allowed the country access to the mechanism of international trade that ultimately helped Scotland become part of a globally successful power.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe formal joining of the two kingdoms was far from universally popular however, and there were was an enduring belief that Scotland’s sovereignty was sold off in the Act of the Union. Robert Burns would later famously write about the Parliamentarians who signed the Act: “I’ll mak this declaration;

“We’re bought and sold for English gold-

“Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!”

Aftermath and legacy

Looking back down the centuries to the Darien episode with the abundance of knowledge we enjoy in the 21st century, it is all too easy to pour scorn on the Scottish pioneers for their naive folly. Yet was the venture really such a terrible idea?

“The Scots were on to something,” says McKendrick, “They recognised the potential that Darien had and indeed Panama would eventually become an emporium for global trade.”

In an ironic conclusion to the tale, Scottish descendants of the Darien expedition would play a role in the establishment of the Panama Canal.

When the colony was abandoned, the Rev Archibald Stobo of the second expedition was shipwrecked in South Carolina where he settled. Rev Stobo’s great-great-great-great-grandson was the future President Theodore Roosevelt, who at the turn of the twentieth century, played a significant role in Panama’s secession from Columbia and the construction of the Canal.

And so it is that a descendant of one of the Darien colonists would achieve where his ancestors failed and finally open “this door of the seas.”

- John McKendrick is the author of the 2016 book Darien: A Journey In Search Of Empire. When researching his book McKendrick, traveled to Panama, retracing the steps of the tragic colonists.