Truth behind the sinking of HMS Hampshire revealed

Twelve authors spent two years painstakingly researching the tragedy – which claimed the life of Lord Kitchener, of “Your Country Needs You” poster fame – and now put an accurate figure of 737 on the number of deaths, estimates of which have wildly fluctuated over the years.

The figure is revealed in a book to be published later this year, HMS Hampshire: A Century Of Myths And Mysteries Unravelled, which also looks at the truth behind other tales surrounding the sinking.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRevenues from the book will help fund restoration of an Orkney memorial to the tragedy at Marwick Head.

Two of the most persistent rumours examined were that the ship sailed through a known minefield and that the military refused to allow local Orcadians to help with rescue attempts. Their conclusions are that the first was down to a simple misprint in an official document and the second did not hold up to close scrutiny, except in just two isolated cases.

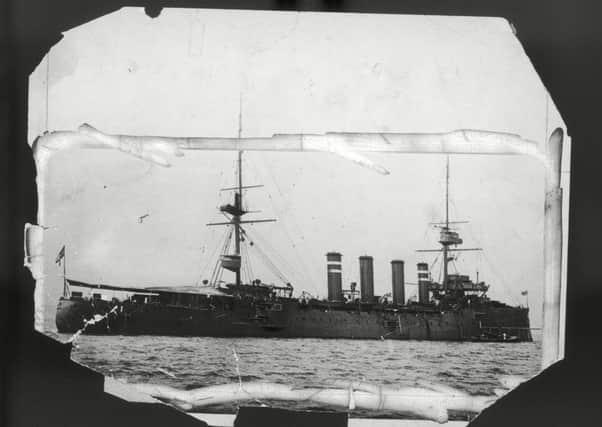

The Hampshire, an armoured cruiser, was en route from Orkney to Russia, taking Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, on a secret mission to bolster support from the Tsar for the war when it hit a mine and sank on 5 June, 1916. There were only 12 survivors.

The death of Kitchener had a profound impact on the country. “Very like President Kennedy or Princess Diana’s deaths in later years, everyone who was alive then would remember the moment they heard about Kitchener’s death even though three weeks later 20,000 died at the Somme,” says James Irvine, one of the authors.

And, much like Diana’s and Kennedy’s deaths, the demise of Kitchener attracted conspiracy theories.

Accusations of incompetence or collusion against the Admiralty have focused on the destruction of another ship, HM Drifter Laurel Crown, on 2 June, blown up by the same minefield laid by submarine U-75, and why the Hampshire was sent through a known danger zone. But Irvine says that rumour comes from a simple misprint in an internal Admiralty document – the date of the destruction of the Laurel Crown should have read 22 June.

Rumours that something sinister was afoot have also been fuelled by accounts from Orcadians claiming they were not allowed to assist in the rescue attempts and were even forcibly stopped by the military when they tried to intervene.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Irvine says careful examination of what is still a sensitive subject in Orkney has revealed such stories are “almost certainly myth” with just two recorded incidents with some basis in fact.

Many of the accounts come from Birsay, which was nearest to the stricken ship but not where rescue efforts were focused, in Sandwick, a few miles south of Marwick Head, where most bodies and survivors came ashore.