The 'uninvited eight' who started the Edinburgh Festival Fringe

In particular, it will explore the case of Glasgow Unity Theatre, one of a string of early-20th century Scottish companies with a left-wing agenda. This was the company that first staged Robert McLeish’s The Gorbals Story in 1946 and Ena Lamont Stewart’s Men Should Weep in 1947, and it was naturally keen to be part of the EIF’s inaugural line-up. Founding director Rudolph Bing, however, decided against.

That isn’t too surprising. Bing’s tastes were at the elitist end of the spectrum and, as an exiled Austrian living in London, he was no expert in the Scottish popular theatre tradition. Attracting local working-class audiences was not high on the agenda of a man who had set his sights on La Compagnie Jouvet from Paris, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Sadler’s Wells Ballet. Most likely, he was also influenced by playwright James Bridie, an EIF adviser, who, as chairman of the Scottish committee of the Arts Council of Great Britain, had been party to the withdrawal of Unity’s funding for what he called its “scatter-brained finance”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo much for internal politics. What happened next is considerably more significant. Because, rather than accept rejection, Glasgow Unity came to Edinburgh anyway. “It was fully aware of its presumption in appearing in the same area as the international giants,” reported The Scotsman, “but even if it only played the role of netboy retrieving the ball behind the goal at the International, Unity was going to be there.”

And it wasn’t the only one. In that summer of 1947, a total of eight companies landed in the city uninvited. They weren’t trying to make a point; they just wanted to get closer to an exciting cultural moment.

For the EIF was conceived not as a three-week carnival of hedonistic pleasure, like a high-art T in the Park, but as a necessary antidote to the pain and division of the Second World War. After so many years of conflict, here was a chance to heal wounds and bring Europe back together.

Look at the comments made by civic dignitaries at the time and they are couched in the language of idealism and hope. Today, you may expect the Lord Provost to praise the festivals in terms of attracting tourists and boosting the local economy, with maybe a passing reference to art if you’re lucky. By contrast, the man in the job in 1947, Sir John Falconer, wrote that he hoped the new festival would give audiences “a sense of peace and inspiration with which to refresh their souls and reaffirm their belief in things other than material”.

A few weeks later, the novelist EM Forster would praise the musicians he’d seen at the Usher Hall, saying, “They are a light in the world’s darkness, raised high above hatred and poverty.”

What artist wouldn’t want to be connected to an event with such lofty aims? Only two years after the war’s end and with rationing still a daily reality, who wouldn’t want to join in this great artistic reconciliation? And so they duly came.

Six were Scottish, two from England. Between them, they took over four theatres that were not being used by the EIF – plus Dunfermline Abbey where the Carnegie Trust backed a production of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Everyman (establishing an out-of-town precedent for impresario Richard Demarco who, in 1995, audaciously extended the Fringe to Dundee Rep).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

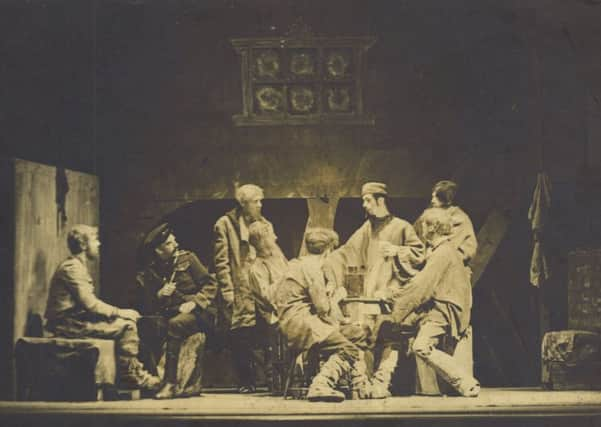

Hide AdAt its own expense, Glasgow Unity found a place to perform at the Little Theatre in the Pleasance where it presented The Lower Depths by Maxim Gorky and The Laird o’ Torwatletie by Robert MacLellan. It had also intended to stage Lamont Stewart’s Starched Aprons, but cancelled when the Arts Council refused to offer a guarantee, giving it the ignoble honour of being the first of a long line of Fringe companies to pull out at the last minute.

Meanwhile, Edinburgh’s amateur Christine Orr Players presented Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the YMCA in South St Andrew Street, attracting some of the company from the Glyndebourne production of Verdi’s Macbeth that was playing in the EIF at the same time. A diary piece in The Scotsman reported that a critic from Latin America thought it was the most interesting production he’d seen during his stay.

At the same venue, you could catch Edinburgh College of Art Theatre Group doing Strindberg’s Easter. And as well as Glasgow Unity at the Little Theatre, Edinburgh People’s Theatre staged Thunder Rock, a wartime allegory by Robert Ardrey, and the Scottish Community Drama Association presented Bridie’s The Anatomist.

Over at the now lost Gateway Theatre at the top of Leith Walk, you could catch a TS Eliot double bill of The Family Reunion and Murder in the Cathedral by the Pilgrim Players from the Mercury Theatre in London. And in the restaurant of the currently abandoned Odeon in Clerk Street (then the New Victoria Cinema), you could see the Lanchester Marionette Theatre putting on a series of short puppet pieces.

What’s notable about these pioneering companies – a Fringe before the name was even coined (see panel) – is how closely they approximate the shape of the gargantuan event we know today. True, there was no stand-up – in fact the line-up was entirely theatre – but the mix was not so different. They were amateur and professional, resident and visitor, highbrow and popular, classic and new.

Over the decades, the word “fringe” has been associated with the underground and the experimental, but this was an accessible line-up pretty much like the programmes the Edinburgh Fringe, for all its surprises and innovations, has offered ever since. As The Scotsman pointed out in advance of the 1947 event, the “balance of the Festival will be righted by the semi-official choices”. Then, that balance was in the number of new and home-grown plays; in subsequent years, the Fringe has continued to go in directions the EIF has not, in a way that has strengthened their interdependence.

Without thinking about it, those companies also established the principles on which the Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society is based. They help account for its phenomenal success. Today we describe it as an “open access” festival and, by turning up uninvited, the companies enshrined the “let’s do the show right here” ethos that holds to this day. On this Fringe, anyone with the gumption and the means to get a show on is allowed to perform. Anything is possible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt says something about those core values that Edinburgh People’s Theatre is still a Fringe regular. Making its 60th appearance this year, the amateur company is staging Sam Cree’s pre-nuptial comedy Wedding Fever at Mayfield Salisbury Church. If you’re looking for the true spirit of the Fringe, that would be a very good place to start.