The technical triumphs that made Trainspotting a trendsetter - Alistair Harkness

Here was a Scottish film with the cult cache of Quentin Tarantino’s still-new Pulp Fiction that also managed to be thoroughly plugged into contemporary British youth culture, while simultaneously drawing from the cinema of Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and, closer to home, the gently subversive humour of Bill Forsyth.

It hadn’t exactly come out of nowhere – director Danny Boyle, screenwriter John Hodge, producer Andrew Macdonald and star Ewan McGregor had already scored a hit with Shallow Grave – but there was still nothing quite like it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen I first saw it at a ‘mystery screening’ at the Cameo Cinema in Edinburgh a week or two before release, the atmosphere and energy in the room was more like a gig than a movie – something amplified by the film kicking off with the thunderous drums of Iggy Pop’s Lust for Life as McGregor’s junkie protagonist, Renton, tore along Princes Street.

The freeze-frame character introductions – borrowed from Scorsese’s Mean Streets – helped set the stylistic tone and while they’ve become a cinematic cliché in the years since thanks to their ubiquity in other movies, Trainspotting still feels fresh thanks to how inventive the rest the film was.

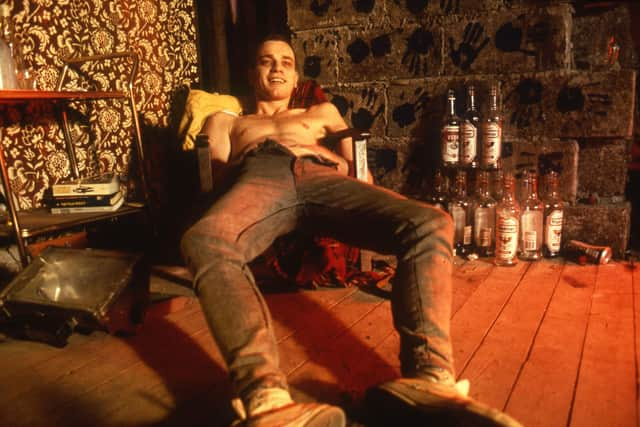

Eschewing social realism, Boyle and Co looked to Francis Bacon and elsewhere for inspiration, experimenting with visuals and colour schemes and adopting the hallucinatory tone of Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh’s other short story collection, The Acid House, something that really came to the fore in the pivotal “toilet scene” when McGregor’s Renton disappears down “the worst toilet in Scotland”.

The mix of the scatological with the surreal was the first indication that this was a film that might take you anywhere. And it did.

Renton’s subsequent “it’s sh*te being Scottish” rant felt like an urgent pushback against the mythological excesses of Braveheart and Rob Roy.

The film’s innovative soundtrack, meanwhile, used contemporary bands and dance music to create a snap-shot of what was going on Britain at that moment, with Boyle also making inspired use of Lou Reed’s Perfect Day to plunge us into the semi-conscious state of Renton as he’s overdosing.

There was a confidence too in it the way it was released as a mainstream movie, which in itself echoed the brazenness of the music industry at the height of Britpop. If you were young and Scottish and loved movies, music and books, it felt like you were at centre of the cultural universe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd yet despite its box-office and critical success, it has remained something of an anomaly in British cinema.

The Full Monty and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels quickly offered the industry more easily replicated models for success and even Boyle’s own belated sequel couldn’t match its impact.

But its positive influences can be felt in other ways.

Subsequent Irvine Welsh adaptations of The Acid House and Filth gave respective career boosts to Scottish directors Paul McGuigan and Jon S Baird and the poetic realism of Lynne Ramsay’s films, the dark sexual undercurrents of David Mackenzie’s early work, the surreal flourishes in Peter Mullan’s Neds, the creative audacity of Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin and the abstract rave finale of Brian Welsh’s Beats offer plenty of examples of Scottish-set films and filmmakers liberated either consciously or unconsciously by the creative leaps that Trainspotting took.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.