The Shetland sea captain who became 'King of the Cocos'

As palms rocked in the south easterly trade winds and his cousin set about restowing their cargo of peppers from Borneo, Clunies-Ross, then 39, was left with a deep impression.

Not only were the uninhabited islands a thing of resounding beauty, they were also ideal territory for a new trade port.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust two years later, the islands were to become the home of the schoolteacher’s son from Weisdale. More than that, they were to become his kingdom.

John Clunies-Ross was hailed the “King of the Cocos” after settling on the Indian Ocean atoll with his wife and children in 1827.

Five generations of the family were to rule over their private fiefdom until 1978 when the land was sold to Australia for £2.5m.

Captain Gordon B Smith, a retired master mariner of Lerwick, researched the Clunies-Ross family history and earlier wrote a detailed account of their time on Cocos Islands, which sit roughly halfway between Australia and Sri Lanka.

Clunies-Ross and his crew “found the islands suitable for establishing a base from which to trade with the pepper ports of Sumatra,” Captain Smith earlier wrote.

He added: “In the presence of his crew John took “possession of the private rights of their soil” and announced his intention of settling upon them.”

John Clunies-Ross arrived on the Cocos Islands, around 11pm on February 15 1827, with his wife, five children and entourage in tow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe raised the Union Jack on South Island and settlement of New Selma nine months later.

“Paths were cut, palms thatched huts built for living quarters and wells dug,” Captain Gibson wrote in in 1992.

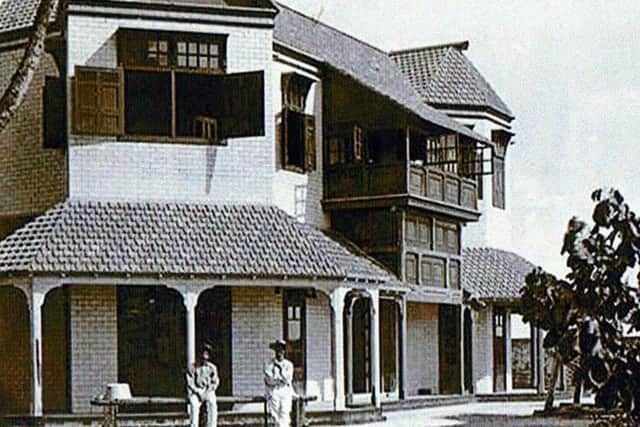

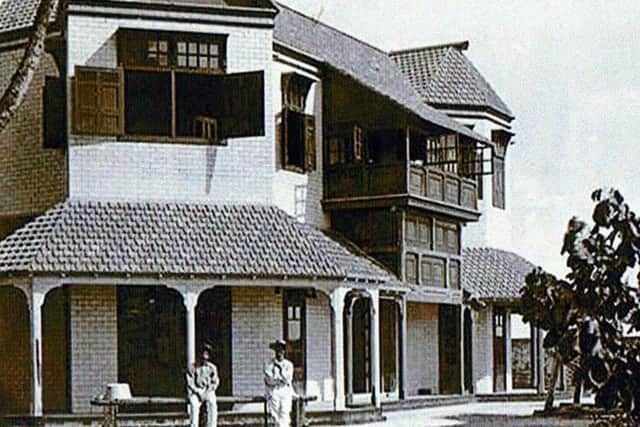

Later, a large house was built using beams of Norwegian Wood, flooring from Singapore board and pillars of island timber.

Lush gardens were cultivated using burnt palm leaves as fertiliser with maize, pumpkins, water melons, bananas all quickly ripening. Pigeons, chickens, ducks, turkeys and sheep were also reared.

“The lagoon was of course an inexhaustible source of food; turtles weighing from 50 to 300 pounds, sharks, oysters and mussels, and many varieties of fish caught either with hook or line or with nets,” according to accounts.

But it was not a case of paradise instantly found for John Clunies-Ross.

The morning after arriving on Cocos Islands, the captain awoke to find past employer Alexander Hare, a British citizen who had settled Indonesia, and as many as 98 slaves living on Home Island and West Island.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHare’s slaves, mainly from Malay, were to later rebel with their presence to sully the reputation of Clunies-Ross in the eyes of Charles Darwin, who wrote of his visit to the Cocos in 1836.

Clunies-Ross deeply resented any suggestion of maltreatment of the people.

In 1837, HMS Pelorus called at Cocos stayed for six days “dispensing justice as if the Cocos were part of the British Empire.”

Clunies-Ross agreed to pay the slaves, mostly from Malay, eight pence for collecting and husking 250 nuts a day with houses and gardens to be provided for each family and single adult.

Passage off the islands was to be offered if requested.

Commander Harding, after questioning the Malays about their treatment, later wrote to Clunies-Ross and said: “Not a shadow of complaint or misrule by you could be established or maintained.”

By 1845 the population of the Cocos community was 200 which included the families of John Clunies-Ross, his son, John George, and two son-in laws.

John Clunies-Ross and his wife Elizabeth both died on the same day on May 24 1854, the cause of death unknown. Both are buried in the grounds of the family home, Oceania House, with a Celtic cross marking the family memorial.

The house still stands today and is now run as a hotel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe family kept strong ties with Scotland. Alfred, the son of John George Clunies-Ross, the second King of the Cocos and S’pia Dupong from Surakarta, was educated at Madras College in St Andrews along with three of his brothers.

Alfred represented Scotland in the first international rugby match against England in 1871. He later returned to the islands and served as a doctor.