Scotsman 200: How quest for Northwest Passage turned into search for tragic hero

INTRODUCTION

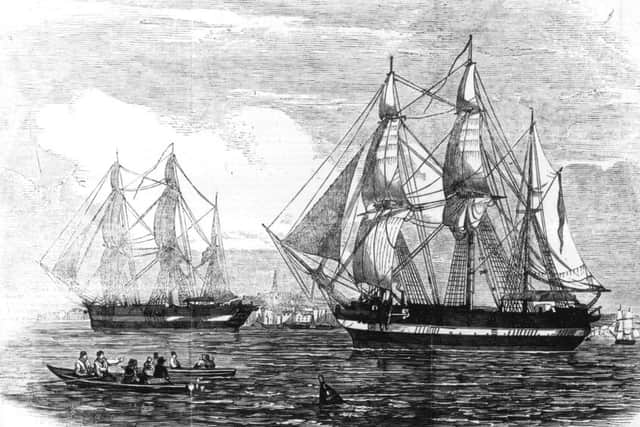

On 19 May, 1845, the Royal Navy officer and arctic explorer Sir John Franklin set sail from Greenhithe in Kent in search of the Northwest Passage, a sea route connecting the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean. His two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were equipped with some of the most advanced inventions of the time, notably steam engines giving a top speed of four knots and a steam-based heating and distillation system that served the dual purpose of keeping the ship warm and providing fresh water for the engine’s boilers. The crew of 24 officers and 110 men were also well provisioned, with three years’ worth of tinned supplies. Given all of the above, there were high hopes of success. However, after a whaling ship reported sighting the two boats moored to an iceberg just outside Lancaster Sound, between Devon Island and Baffin Island, on 26 July, 1845, they were never seen again. Two years later, under pressure from Franklin’s wife, the Admiralty offered a reward of £20,000 for anyone who could find the expedition. Many tried, and many died trying, but it wasn’t until 1854 that the Scottish explorer John Rae discovered their true fate. Below, we include an edited extract from The Scotsman dating from 28 August, 1852, speculating - with misplaced optimism - about the fate of Franklin with searches still ongoing, and then a report on John Rae’s findings from 1854. Thanks to Rae’s grisly observation that “From the mutilated state of many of the corpses... it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource – cannibalism” – Rae was shunned by the British establishment and never received the credit he was due during his lifetime.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: SATURDAY, 28 AUGUST, 1852

Arctic expedition - Sir J Franklin

“What news of Sir John Franklin? Have any traces of his whereabouts been discovered? Has any light been thrown upon the fortunes of himself and his crews?” We hasten to say; on the authority of those best qualified to form an opinion upon the subject, that hope of Sir John Franklin’s safety is by no means to be abandoned, for the probabilities of his existence in some Polar region not yet explored are far greater and more numerous than the probability of his total loss. We say total loss – because in any other case than that of foundering in deep waters some vestige of wreck would, ere this, have been detected by the many keen-sighted and experienced investigators engaged in the search. We will remind the impatient or ill-informed that the total extinction of two British men-of-war, commanded by such officers as Sir John Franklin and Captain [James] Fitzjames, and manned and equipped as the vessels of his expedition were, is an event so contradictory to all experience of the causalities of the Polar regions, as to amount to the strongest improbability. It may well be to add, moreover, that in the opinion of most competent judges, such as Colonel [Edward] Sabine, Mr Augustus Peterman, and others, there is a greater probability of finding Sir John Franklin’s expedition in regions to which search has not yet been extended than in the more familiar localities throughout which search has hitherto been made. The arguments of those who maintain the improbability of maintaining life in higher latitudes than those already explored are refuted by well-established facts, to which we will presently advert more in detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir John Franklin sailed from Kent, with the Erebus and Terror in May 1845, and arrived at the Whalefish Islands on 4 July. His last despatches were from this point, bearing the date July 12. The Erebus was spoken for on the 22nd of the same month by Captain Martin, of the whaler Enterprise, in latitude 75 deg. 10 min., longitude 60 deg. west. The Prince of Wales whaler reported that on the 26th of July, 1845, she saw Franklin’s vessels in latitude 74 deg. 48 min., longitude 66 deg. 13 min. They were then moored to an iceberg awaiting an opening in the middle ice to enable them to cross over to Lancaster Sound. Between this period and 23 August, 1850, five years and a month, when the first traces were discovered by Captain [Erasmus] Ommanney, of her Majesty’s ship Assistance, at Cape Riley, no intelligence, direct or indirect, was received of the missing ships. The evidences afforded by these first traces were added to largely four days after (27 August, 1850), by Captain [William] Penny’s alighting at Beechy Island upon the spot where Franklin spent his winter of 1845-6.

Early in 1850 the admiralty placed four ships in commission under the command of Captain Horatio T. Austin, C.B., who had served in an exploring voyage under Sir Edward Parry, for the purpose of examining Barrow’s Straits, under a notion that Sir John Franklin might be retracing his course eastward in boats, or even in the ships themselves, having relinquished the hope of making a north-west passage. The squadron under Captain Austin consisted of his own ship the Resolute, the Assistance, Captain E. Ommanney, and the steam-tenders Pioneer, Lieut. Osborn commanding, and Intrepid, Lieut. Cator commanding. The Lords of the Admiralty ventured to associate William Penny, an experienced whaling captain of Dundee, with their own commissioned officers. Mr Penny, after receiving instruction from the Admiralty, proceeded to Aberdeen and Dundee, where he purchased two new clipper-built vessels, which were named respectively the Lady Franklin and Sophia, the latter in compliment to Miss Sophia Cracroft, a niece of Sir John Franklin, and most devoted companion of his noble-hearted wife. These vessels were placed under Mr Penny’s command.

[At Beechy Island] Mr Penny discovered unquestionable traces of Sir John Franklin on the 27th August, and here the ships were moored to examine it as carefully as possible. The landing party was under the orders of Mr Stuart, commander of the Sophia, to whose intelligence, perseverance, and zeal, Captains Austin, Penny and Dr Sutherland combine in bearing testimony.

“Traces,” observes the latter, “Were found to a great extent of the missing ships: tin canisters in hundreds, pieces of cloth, ripe, wood in large fragments and in chips: iron in numerous fragments, where the anvil had stood, and the block which supported it; paper, both written and printed, with the dates 1844 and 1845; sledge marks in abundance; depressions in the gravel resembling wells which they had been digging; and the graves of three men who had died on board the missing ships in January and April 1846.”

Here, then, was unquestionably a station of Sir John Franklin’s party, and occupied until the 3rd of April, 1846, at least. In the opinion of Captain Penny and others it was occupied for a look out up the Wellington Channel, to watch the first opening of that icy barrier which so frequently seems to block it up. Sir John Franklin’s instructions, in 1845, were to proceed to the Wellington Channel, and if possible, through it, and the marks of a hasty departure thence may be more reasonably accounted for by a sudden opening in the ice, of which the ardent spirit of Franklin would prompt him instantly to avail himself, than the wild supposition which has been broached of his retreat from an onslaught of savages – a feat quite inconsistent with the habits and disposition of the harmless and inoffensive Esquimaux.

There is a narrative of four Russian sailors who subsisted in Spitzberen on the product of the country for six years and three months reprinted in Captain Mangle’s volume from the Annual Register for 1774. If four Russian mariners, with a few ounces of tobacco, twelve musket charges of powder and shot, and a small bag of flour, as their only stores to start with, could subsist for six years and three months in Spitzbergen, how long can the crews of two English men-of-wars, commanded by officers of the Arctic experience, fertility of resource and unconquerable courage of Sir John Franklin and Captain Fitzjames, preserve their lives? We leave others to work out this sum, and for ourselves say, Nil Desperandum. We do not write in this hopeful strain at random, or wantonly to awaken delusive hopes which we feel to be unfounded, but deliberately express convictions formed after much thought, diligent inquiry, and painstaking investigation.

The full report of this account is available on the Scotsman Digital Archive