Scotsman 200: Dr Livingstone mapped a continent in good faith

INTRODUCTION

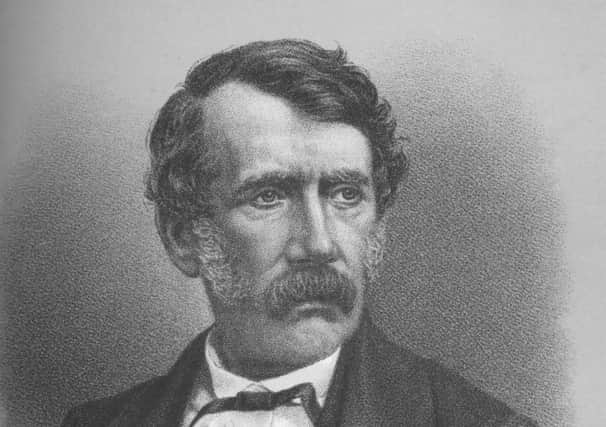

In May 1856, four years after leaving the Atlantic coast of Angola, the Scottish explorer and missionary David Livingstone reached the mouth of the Zambezi on the Indian Ocean, becoming the first European to cross southern Africa. Along the way, he had filled in huge gaps in western knowledge, notably reaching the waterfall known locally as “Mosi-oa-Tunya,” or “the smoke that thunders,” which he named Victoria Falls. When he returned to Britain he was hailed as a national hero – not least in the pages of The Scotsman, as demonstrated by the lavish praise heaped on him in the extensive leader comment of 24 December 1856, reprinted below. Perhaps the most telling bit of Scotsman coverage, however, dates from the edition of 17 December. An eye witness account of his arrival at Southampton, it notes that as a result of having “scarcely spoken the English language for the last sixteen years” Livingstone now “hesitates in speaking... is at a loss sometimes for a word, and the words of his sentences are occasionally inverted.” The report also states: “He saw a multitude of tribes of Africans and several races, many of whom had never seen a white man until he visited them. They all had a religion, believed in existence after death, worshipped idols and performed religious ceremonies in groves and woods.” What a wonderful reminder that, well within the lifetime of this newspaper, there were still vast swathes of the world map that remained entirely blank to us, their inhabitants an unknown quantity. And how strange and somehow moving that, even in a relatively short news report, this evidence of an apparently universal human need to believe in the hereafter should be seen as central to the story.

WEDNESDAY, 17 DECEMBER, 1856

Dr Livingstone, the African Traveller

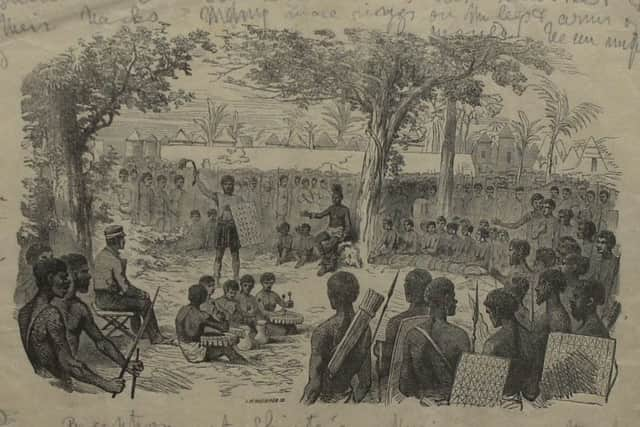

Dr Livingstone reached Southampton from London at seven o’clock on Thursday night. Mr Randall, with whom Mr Livingstone has been staying, and other gentlemen, met him at the railway station. On Friday, a number of gentlemen paid their respects to him, although his arrival in the town was not generally known. He is nearly forty years of age, his face is furrowed through hardships and is almost black with exposure to a burning sun. He hesitates in speaking, has a peculiar accent, is at a loss sometimes for a word, and the words of his sentences are occasionally inverted. His language is, however, good, and he has an immense fund of the most valuable and interesting information, which he communicates most freely. He is in good health and spirits. He has scarcely spoken the English language for the last sixteen years. He lived with a tribe of Bechuanas, far in the interior, for eight years, guiding them in the paths of virtue, knowledge and religion. He, in conjunction with Mr Oswald, discovered the magnificent Lake Ngami, in the interior of Africa. He traced by himself the course of the great river Zambesi, in Eastern Africa, and explored one of the extensive and arid deserts of the African continent. Dr Livingstone explored the country of the true negro race. He saw a multitude of tribes of Africans and several races, many of whom had never seen a white man until he visited them. They all had a religion, believed in an existence after death, worshipped idols and performed religious ceremonies in groves and woods. They considered themselves superior to white men, who could not speak their language.

WEDNESDAY, 17 DECEMBER, 1856

Dr Livingstone’s African Discoveries

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The members of the Royal Geographical Society of London held a special meeting on Monday night to present the Society’s gold medal to the Rev. Dr Livingstone for his discoveries in Central Africa. The Society’s rooms was crowded to excess. The chair was taken by Sir Roderick Murchison, President of the Society. The President, in opening the proceedings, said they were met to welcome Dr Livingstone on his return from South Africa to his native country after an absence of sixteen years, during which, while endeavouring to spread the blessings of Christianity through lands never before trodden by the foot of a British subject, he had made geographical discoveries of incalculable importance, which had justly won for him the Victoria or Patron’s gold medal of that Society. (Cheers.) When that honour was conferred in May 1855 for traversing South Africa from the Cape of Good Hope by the Lake Ngami to Linyanti, and thence to the west coast, Lord Ellesmere, their then President, spoke of the scientific precision with which the unarmed and unassisted English missionary had left his mark on so many important stations of regions hitherto blank. (Hear, hear.) If for that wonderful journey Dr Livingstone was justly recompensed with the highest distinction their Society could bestow, what must now be their estimate of his prowess when they knew that he had retraversed the vast regions which he first opened out to their knowledge; nay, more, that after reaching his old starting point at Linyanti, in the interior, he had followed the Zambesi, or continuation of the Leamhye river, to its mouths on the shore of the Indian Ocean, passing through the Eastern Portuguese settlement of Tête, and thus completing the entire journey across South Africa?

In short, it had been calculated that, putting together all his various journeys, Dr Livingstone had not travelled over less than 11,000 miles of African territory; and he had come back as the pioneer of sound knowledge, who, by his astronomical observations, had determined the site of numerous places, hills, rivers, and lakes, nearly all hitherto unknown, while he had seized upon every opportunity of describing the physical features, climatology, and even the geological structure of the countries he had explored and pointed out many new sources of commerce as yet unknown to the scope and enterprise of the British merchant. (Cheers.) Dr Livingstone was received with much cheering. After expressing thanks he said: “The English people and Government have done more for Central Africa than any other in the way of suppressing that traffic which proves a blight to both commerce and friendly intercourse. (Cheers.) May I hope that the path which I have lately opened into the interior will never be shut, and that in addition to repression of the slave trade, there will be fresh efforts made for the development of the internal resources of the country. (Hear, hear.) Success in this, and the spread of Christianity alone, will render the present success of our cruisers in repression permanent. (Hear, hear.) I cannot pretend to a single note of triumph. A man may boast when he is putting off his armour , but I am just putting mine on; and, while feeling deeply grateful for the high opinion you have formed of me, I feel also that you have rated me above my deserts, and that my future may not come up to the expectations of the present.”

WEDNESDAY, 24 DECEMBER, 1856

Dr Livingstone (From the day’s Leader article)

Dr Livingstone’s great achievement may be described in a few words: he has explored the whole of the immense region of Southern Africa, from the Atlantic to the Eastern Ocean. He has discovered rivers, lakes, cities, nations, even a new climate. First, he penetrated from the Cape of Good Hope upwards to Lake Ngami, and thence, by a direct route, to Linyanti, a point more than twenty-four degrees from the southern extremity of the continent. Being now within ten degrees of the equator, he struck off to the west, and succeeded in reaching the Portuguese settlements on the coast. Following these indications on the map, the reader will immediately perceive what vast blanks of geography were removed in the course of this single journey. From the western coast, Dr Livingstone returned to Linyanti, and followed the course of the Zambesi river to its junction with the eastern waters in the channel of Mozambique. Mark these routes upon the map with a red line, and it will intersect Africa from the south hundreds of miles beyond the limits of all former research; and from ocean to ocean, west to east, through regions hitherto as unknown as America before the voyages of Columbus. Moreover, Dr Livingstone carried with him a proficient knowledge of at least five sciences, so that as he journeyed he made incessant observations, astronomical, geological, and geometrical, marked the varieties of climate, and took botanical and zoological notes innumerable. Still further, he collected a large store of information connected with the commercial products of the various territories he travelled, the industrial habits of the natives, their disposition to trade. He has demonstrated the existence of a great line of water communication from the western settlements northwards, begun by the Coanga, continued by the Kasye, and completed by the Leambye, close to the navigable Lake Ngami. Thence another line, of equal importance, tends eastward along the course of the noble Zambesi, which in fact is identical with the Leambye, and which, running through the towns of Tête and Sena, breaks into several channels, forming the delta of the Quillimane, and is emptied into the Indian Ocean. For seventeen years, smitten by more than thirty attacks of fever, endangered by seven attempts on his life, continually exposed to fatigue, hunger, and the chance of perishing miserably in a wilderness shut out from the knowledge of civilised men, the missionary pursued his way, an apostle and a pioneer, without fear, without egotism, without desire of reward. Such work, accomplished by such a man, deserves all the eulogy that can be bestowed upon it, for nothing is more rare than brilliant and unsullied success.

More interesting, however, than the geographical delineation of interior Africa is effected by Dr Livingstone in his account of its varieties of climate and population. Turn to any Gazeteer, and we find the mysterious expanse of the south described as blazing in the rays of an insufferable sun, and only tolerable to the tropic constitution of the Ethiopian race. Many circumstances combined to perpetuate this illusion. As the Portuguese in the East, during the sixteenth century, were accustomed to describe the Spice Islands as inaccessible desolations, encompassed by rocks, shoals, and all the dangers of the sea, so the Boer settlers along the outskirts of African civilisation were eager to build up a barrier of invisible terrors between the coast and the central kingdoms of the south. Their object was monopoly, of course. Had Dr Livingstone been persuaded by their representations, he would never have ventured into a region. But he refused to take alarm and pushed on. Sixteen degrees of latitude were found as hot and arid as they had been pictured; the western coast was indeed a serpent-breeding mass of swamps and forests; the eastern coast was often uninhabitable by Europeans ; but beyond the twentieth degree of south latitude, not only a different race, but a different country was found. It was elevated, it was cooled by pleasant breezes, it abounded in fruit and grain, it was watered by a perfect maze of rivers and streams of all sizes. Some of them were broad and deep and never dry during the hottest season. This was the true home of the Nigritina family, not of the rusty Bechuann, but of the curly-headed, jet-black Negro, who was once transported from these remote kingdoms to the British West Indian settlements, and who is even now brought down, at times, to the coast, and shipped for Cuba or Brazil. These nations have never carried on, however, any direct communication with the sea, the maritime tribes and colonists having cut them off – a policy which it will be difficult to carry out after the researches of Dr Livingstone have been made known to the commercial communities of Europe and America. It will no longer be possible to delude the natives by accounts of English cannibalism.

The great river discovered by Dr Livingstone, which intersects the southern region of the continent from one seaboard to another, traversing in the interior territories abounding in natural riches, and inhabited by an intelligent though simple race of people, is a pledge to Africa of future intercourse with Europe, and of comparative civilisation. The most extraordinary circumstance announced by Dr Livingstone is the salubrity of these vast countries. “In some of the districts of the interior and among the pure negro family many of the diseases that affected the people of Europe are unknown. Small-pox and consumption have not been known for twenty years, and consumption, scrofula, cancer, and hydrophobia are seldom heard of.” So healthy are the natives, and so free from weakening taints, that pure-blooded negroes from beyond the twentieth degree of south latitude are treasures in the Cuban or Brazilian market. They are brought down to the coast, men and women, in chains, and so far from being willing to quit their homes, are in most cases captured after a fierce and sanguinary battle with the tribe to which they belong.

This great traveller deserves a monument, and will, probably, build one for himself. He will publish the record of his wanderings, and that book will be a more enduring and appropriate memorial to his unostentatious genius and simple heroism than any tablet, or statue, or emblem whatever. But he has not yet completed the great work of his life. He is again preparing to carry the great sympathies of civilisation into the depths of Africa.

The full report of this account is available on the Scotsman Digital Archive