Scotland's ‘frontline’ part in the Cold War to be recalled in new exhibition

It was the defining conflict of the second half of the 20th century and a superpower stand-off that had the world on the brink of catastrophic destruction for decades.

Now the first major exhibition of its kind is to recall the impact of the “critical” part Scotland played in the Cold War over the course of more than 40 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

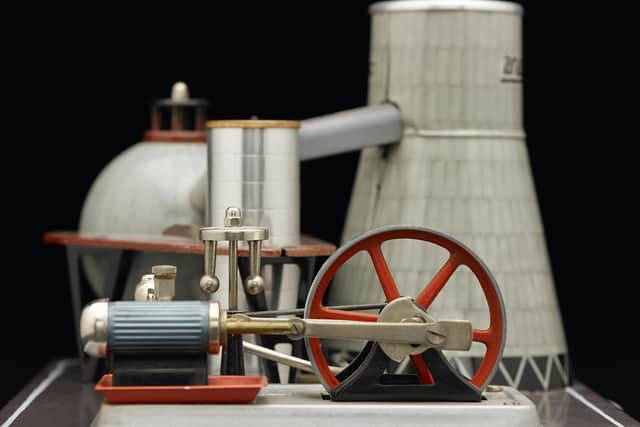

Hide AdIt will explore the roles played by Scots in the military and intelligence services, the key protests and campaigns for peace and against the presence of weapons of war in Scotland, and how military bases, power stations and bunkers transformed landscapes and local communities.

More than 190 objects will be brought together under the one roof for the first time at the National Museum of Scotland, in Edinburgh, in July for a six-month exhibition, which will recall the ever-present risk of a nuclear attack due to the country’s geographical and logistical position between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The exhibition has emerged from a three-year research project led by the National Museum and Stirling University into how the Cold War features in official collections around Europe. The £1 million initiative, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, was instigated in 2021 to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The exhibition will explore the roles played by movements like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and organisations such as the Royal Observer Corps, a uniformed civilian organisation tasked with preparing for nuclear disaster in Britain.

Meredith Greiling, principal curator of technology at the National Museum, said: “The three-year research project really came out of the fact that the entire contents of a Royal Observer Corps underground monitoring post at Turnhouse in Edinburgh when it closed at the end of the Cold War.

"We literally acquired everything that was in this tiny bunker more than four metres below ground, including things like a bucket toilet, loo rolls and boxes of biscuits.

“The idea was that the Royal Observer Corps would be in position in stations across the whole of the UK to monitor the impact of a nuclear bomb going off with specialist equipment. They were prepared to spring into action should the worst happen.“Given that it’s now over 30 years since the end of the Cold War, a lot of us will have some memories of it, but a lot of young adults will have no memories of it, or their understanding of it will be from popular media, including films which are very American-centric.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People don’t really think of Scotland as a Cold War site, but actually it really was. Everything about the geography and topography of Scotland was perfectly aligned with being on the frontline of the Cold War.

"It was an ideal place to observe and listen in to Soviet submarines and aircraft, but there was no single Cold War site in Scotland.

“It involved Scots in so many different ways, whether they were in the military or volunteer service, were involved in the protests or married someone in the American military.”

The exhibition will recall the long-term impact of the use of atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of the Second World War, including how the threat of another attack was at the heart of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union for decades.

Ahead of the opening of the exhibition, which features numerous objects going on public display for the first time, the museum has made a series of short films drawing on archives, collections, footage and new interviews with experts to explore how the Cold War impacted on Scottish lives, politics, landscapes, technology and power supplies.

Ms Greiling said: “At the same time as nuclear weapons were under-pinning the east-west confrontation in the 1950s, nuclear power seen as a brave new world of opportunity in Scotland.

“It was very much promoted as modern technology which was the safe, clean alternative to coal, which would provide limitless energy and massively improve the standard of living.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Nuclear power stations had a huge impact on fairly remote communities which were struggling to keep people after the Second World War. They brought thousands of people, new housing and infrastructure to these areas.

“A huge exhibition on industrial energy was held in Glasgow as part of a Festival of Britain in 1951. The final room that you went into, which was called the ‘hall of the future, was all about nuclear power.

“But there there was always an undercurrent of fear with nuclear power as it was a side product of the plutonium that was being produced for atomic weapons.

“A theme we follow throughout the exhibition is that duality of fear and optimism.”

The exhibition will recall the secret United State intelligence operations on the Soviet Union carried out at Edzell, in Angus, and controversies such as the arrival of the American navy and the presence of its nuclear weapons at the Holy Loch, in Argyll, until after the Cold War ended.

Ms Greiling said: “Having America’s nuclear deterrent in Scottish waters and the presence of thousands of service personnel here very much put Scotland on the frontline of the Cold War.

"Some people obviously didn't like Americans being stationed here and felt that it made Scotland a target.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Huge peace protests were staged in Scotland throughout the Cold War, which brought together people from the churches, politicians and women’s groups.

“But we will also be highlighting how the Cold War was not a sustained period of terror and imminent fear of nuclear annihilation.

"There were obviously moments of that, but there were also moments of friendly relations between Scotland and the Soviet Union.

“There was a Scottish-Soviet friendship society which organised tours of the Soviet Union. We have got tourist brochures and souvenirs that were brought back to Scotland.

“There were also quite a lot of cultural and soft diplomacy efforts, including a visit of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich to the Edinburgh International Festival in 1962.

“We’re very keen to show that there were peaks and troughs in the temperature of the Cold War."

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.