Outlander: A timeline of the Battle of Culloden

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

It would take over 260 years before such a subject would divide families again, but on April 16, 1746 in the final fight of the Jacobite rebellion, clan members fought on both side of the battle.

The Jacobite army, lead by Bonnie Prince Charlie, were outnumbered by 1,000 government soldiers, and slaughtered in numbers. It had been a long, hard campaign for the Scots - and tired and hungry, they finally met their match on a wet, cold morning on Culloden field.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe night before the battle took place, Lord George Murray - the Jacobite general - decided that their best move would be to sneak up upon the Redcoats in the dead of night.

3,000 men set out across the swampy moors and thick woodlands, making the 20 mile hike to where the British army had set up camp. In the dark of night, weary with a long campaign, the men grew disorientated from hunger and exhaustion.

After a heated discussion, General Murray decided to abort the plan, with dawn breaking and still a few miles to go, the men turned back towards camp, taking the 20-mile trek back through the moors.

The British army scouts got wind of the approaching Jacobites, and prepared to set out after them.

The Jacobites were beyond deprived by the time they returned to Culloden. Many men set out in search of food, there being no provisions left at camp, while other simply settled down in ditches to catch a few hours sleep.

By 8am, on the morning of the 16th, the Jacobite army were informed of the approaching British. The men struggled to assemble, many going on less than an hours sleep. By comparison, the British army had been well fed, watered and rested the night before - it being the Duke of Cumberland’s 25th birthday, a small celebration had taken place - leaving many of the men in high spirits.

By 10:30am the Jacobites were one mile east of Culloden, scattered and disorganised after the night march. The British were marching in three columns between Nairn and Culloden, rapidly gaining ground.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBetween 11am-12pm the Jacobites spotted the government army in the distance and gradually began to move into position.

Around 12.30pm, the first cannon is fired, from the Jacobites who were trying to destroy the British cannons, without much success. An eyewitness account from Edward Linn, who was a soldier with the 21st Royal Scots Fuziliers, on the Government front line, wrote in a letter to his wife after the battle: “They fired two pieces of cannon first upon us; we returned them six. They choosed that bogie moor to fight in by reason they thought we could not bring up our cannon through it, but, thank God, they were all mistaken.”

Even the wind was working in the British army’s favour, with the smoke from the cannon fire blowing back towards the Jacobite army, concealing the Redcoats from view. The British army fired volley after volley toward the Jacobites, while they held still, waiting for the call to charge.

Five minutes after the first cannon fire, the call is given to charge, and the Jacobites advance upon the British soldiers. The British switch to a grapeshot, which is effective in wiping out the front line.

15 minutes into the battle, the ranks were close enough to engage in hand to hand combat. The Atholl and Locheil regiments manage to break the British front line, but around 700 of their men were slaughtered in less than three minutes.

Around this time, the British regiments start to surround the Jacobites, who are struggling to charge through bog.

By one o’clock, the Jacobite soldiers are beginning to retreat and Bonnie Prince Charlie - who was 300ft behind the front line - is escorted away from the fighting. The fight is considered over, and 1,500 Jacobite men are lost.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDonald Mackay of Acmonie, Glen Urquhart was a Jacobite volunteer soldier, when he was a young boy, and joined the Jacobites on the morning of the battle, along with his father and older brother.

He escaped the field, but later surrendered and was then transported to the West Indies. He escaped again as a stowaway to Jamaica where he worked on plantations before finally returning to Scotland as an old man. He wrote his account, originally in Gaelic, of his battlefield experience.

“The morning was cold and stormy as we stood on the battlefield - snow and rain blowing against us. Before long we saw the red soldiers, in battle formation, in front of us and although the day was wild and wet we could see the red coats of the soldiers and the blue tartan of the Campbells in our presence.

“The battle began and the pellets came at us like hail-stones. The big guns were thundering and causing frightful break up among us, but we ran forward and - oh dear!, oh dear! - what cutting and slicing there was and many the brave deeds performed by the Gaels. I saw Iain Mor MacGilliosa (Big Iain Gillies) cutting down the English as if he was cutting corn and Iain Breac Shiosallach (Freckled Iain Chisholm) killing them as though they were flies.

“But the English were numerous and we were few and a large number of our friends fell. The dead lay on all sides and the cries of pain of the wounded rang in our ears. You could see a riderless horse running and jumping as if mad. When I saw that the battle was lost, I thought it best to leave and make for home. I said this to my brother who was near me and we made in the direction of Inverness as quickly as we could. When we reached Culcabock we stopped, feeling faint with hunger. I had some oatcakes in my bag and we got a drink of milk from an old lady who was beside the road. “How did the day go?”, she asked.

“Badly for the Prince,” we replied, and left in haste. We went through the river near the islands above the town of Inverness and arrived home during the night. My father arrived safely in the morning and boundless was my mother’s joy at having us back home safe and well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn less than an hour, Culloden saw the deaths of 1,500 Jacobites and officially 50 Government men.

Debbie Reid, of the Culloden Battlefield and Visitor Centre, said: “The Frasers fought on the Jacobite side and saw some of the heaviest losses as they were in the middle of the front line and were among the first to charge. It is estimated they lost up to 250 men at Culloden.

“The Mackintosh clan were also on the Jacobite side on the front line and again losses were heavy. Only three out of 17 Mackintosh officers survived the battle.

“McGillivrays again fought on the front line for the Jacobites so had high casualties and their chief fell during battle and the spot where he fell is now marked by the ‘Well of the Dead’ on the field, although the chief was later buried in Petty Church graveyard.

“The MacDonalds were largely on the left hand side of the front line so escaped the hand to hand fighting thus many of them were able to retreat though many were captured for their part in the Jacobite Rising.

“Other key clans on the Jacobite side included the MacLeans, MacLeods and Camerons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Stewart clan fought on both sides with men in the Atholl Brigade and the Appin Stewarts for the Jacobites and in the Scots fusiliers on the Government side. Similarly clans such as Gordon, Campbell, Chisholm and Forbes had men on both sides.

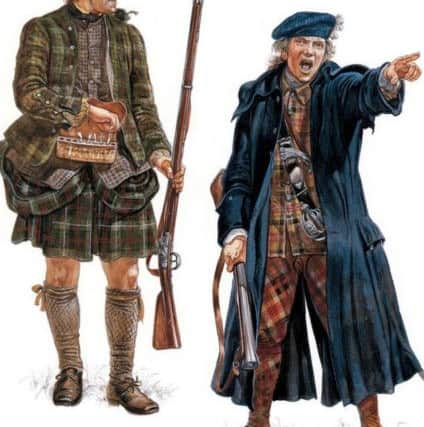

“It is hard to give accurate figures for those who died at Culloden. The Jacobite records are much better preserved than the Government but tracking specific people is difficult. After the battle men would have lain on the field for up to three days before locals were rounded up into burial groups to bury the dead in mass graves which are still on the field today. Determining which clan people were from was extremely difficult. There were no clan tartans at this time so there was little to go on to identify the men.”

In the days following, Lord Cumberland gave the orders that no wounded man on the battlefield be shown mercy - the Redcoats methodically searched the battlefield, killing any survivors.

While many of the high ranking prisoners were executed for treason, the common solider were actually treated leniently in relative terms.

936 men were sent to the colonies and 222 more were exiled. Only one in 20 common soldiers were actually sent to trial due to the high number of men, with 905 prisoners eventually released when the Act of Indemnity passed in June 1747. Another 382 were set free, being exchanged for prisoners of war being held in France.

Read More

•Find out more by visiting the Culloden Battlefield & Visitor Centre

•All images used with permission of The National Trust for Scotland