List of '˜Scots witches' published online for first time

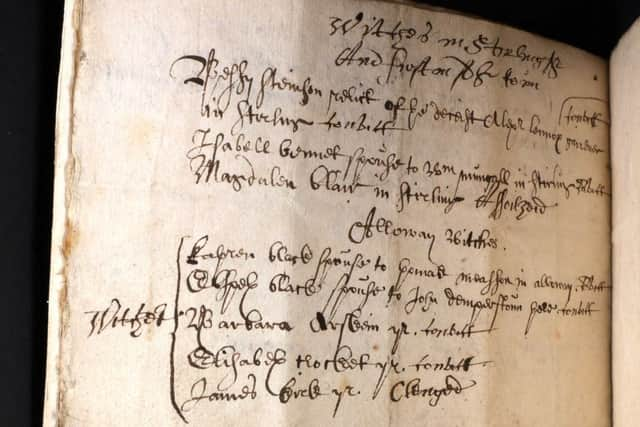

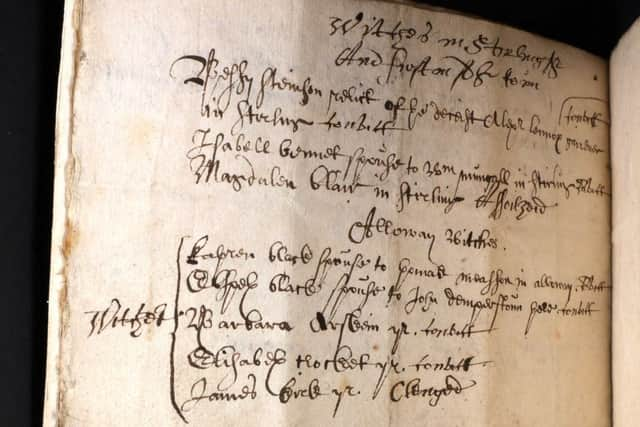

The 350-year-old book, entitled the Names of Witches in Scotland, 1658, documents a time when persecuting supposed witches was rife.

The list of Scottish witches has been published on Ancestry, a family history website.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad102 names are listed, but historians say this is only the tip of the iceberg, as between 3,000 and 5,000 people were accused of being witches in 16th and 17th century in Scotland.

Those who practised homeopathy and folk medicine were the usual suspects for witchcraft.

Their treatments sometimes helped poor communities but accusations of witchcraft could crop up if they didn’t work.

While there was not a set practice, those accused would often be questioned by a local priest or bishop, who may try to draw a confession from them.

While the details of what happened to the suspect witches listed are vague, one, James Lerile, of Alloway, Ayr, is described as “clenged” in the book, a term that means “made clean”.

This suggests James was either banished or killed.

Punishments for the crime of witches varied, but man who were presumed guilty were strangled to death before their bodies were burned.

Among the names of those is accused, is a confession.

A note on Helene Minhead of Irongray, Dumfries, reads: “Her Confessione Is In The Hands Of Mr. Patrike Cuamlait Minister At Irongray.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther details offer small insights into the lives of those accused.

Ancestry Senior Content Manager Miriam Silverman said:”Many of us have donned a black dress, pointy hat and even green face paint to go to Halloween parties as witches, but that’s our almost comic interpretation of something mysterious and scary that people feared in the past.

“In the 17th century, people believed that the unholy forces of witchcraft were lurking in their communities, and those accused of being witches were persecuted on the basis of these dark suspicions.

“Whether your ancestors were accused witches or not, you can find out more about them and their lives by searching these - and many other collections - online today.”

Other details give clues of the suspects’ lives.

Jon Gilchreist and Robert Semple from Dumbarton are recorded as sailors.

The Wellcome Library, which holds the records, allowed them to be dignitalised.

Dr Christopher Hilton, Senior Archivist at Wellcome Library said: “This manuscript offers us a glimpse into a world that often went undocumented: how ordinary people, outside the mainstream of science and medicine, tried to bring order and control to the world around them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This might mean charms and spells, or the use of healing herbs and other types of folk medicine, or both. We’ll probably never know the combinations of events that saw each of these individuals accused of witchcraft.

“It’s a mysterious document: we know when it entered Henry Wellcome’s collections, and a little about whose hands it passed through before that, but not who created it or why.

“It gives us a fleeting view of a world beyond orthodox medicine and expensively trained physicians, in which people in small towns and villages looked for their own routes to understanding the world and came into conflict with the state for doing it.

“We’re delighted to share this insight into the past with a wider audience.”