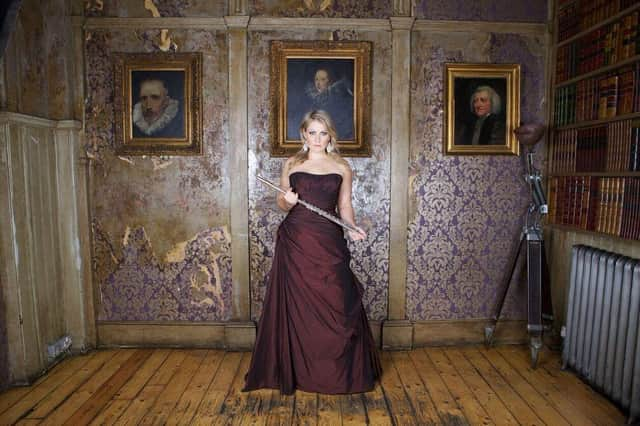

Katherine Bryan: ‘My question was, how about writing me a concerto?’

Bright young composer, on the brink of acceptance into a notoriously difficult profession, gets noticed by dazzling star flautist. Next thing he knows, he’s been asked to write a concerto for her. It sounds like the sort of thing that only happens in films, right?

Wrong. New Cumnock-born Jay Capperauld, having then just graduated from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, was one of several “apprentice” composers active on the Royal Scottish National Orchestra’s original Composers Hub programme in 2015/16. The talent-spotter was the principal flautist and concert soloist Katherine Bryan. “Jay’s piece at that event really spoke to me,” she recalls. “I didn’t know him, but that evening I stalked him online, sent him a message and asked if he’d written anything for flute.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt turned out he hadn’t, but he immediately offered to write Bryan a short solo piece. “It’s called The Pathos of Broken Things, which we worked together on and filmed at Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens and posted on YouTube, just like a music video,” she explains.

But a more ambitious work was to follow. “Before he’d even started the solo piece, my question was, ‘how about writing me a concerto’? The flute repertoire is starved of them.” The result will be unveiled in the exalted company of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the RSNO’s close-of-season concerts in Edinburgh and Glasgow on 3 and 4 June.

Capperauld called his new concerto Our Gilded Veins, which not only points to its inspiration from the Japanese art of Kintsugi – the idea that a broken object can be repaired and made useful again, accepting its imperfections as part of the object's history – but connects it, philosophically and in turn musically, to the earlier solo piece, from which some material is derived.

It also owes much to Covid, which delayed the original premiere in September 2020, and resulted in Capperauld, with “more head space”, rewriting half the work.

“He’d already based it on the human nature of being broken, and how rebuilding things that have been seen as a failure into something positive is really important these days,” says Bryan. “Many people are very open to talking about mental health, which is such a positive thing, so we wanted to relate the piece to that.”

In Capperauld’s mind, the flute in this concerto undergoes the same upheaval as any normal person. “Reality is neither expressed as wholly optimistic nor wholly pessimistic,” he believes. “It lies in a middle ground”. In Bryan’s mind, he’s written for her a “very relatable, big and bold, if incredibly difficult piece.”

“It doesn’t follow traditional patterns at all, but I like the spontaneous feel that comes with that,” she says. More importantly, it’s something she gets a real kick out of playing. “There’s a compelling sense of inner energy and emotional honesty about it that will connect directly with audiences.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLearning it, however, was hampered by unforeseen events. “Just as I was getting into it in February, I got a really bad case of Covid, which badly affected my breathing and kept me in bed for much of the time,” says Bryan. Fully recovered now, and with a month’s intense practice behind her, she’s ready for the long-awaited premiere.

But the impact of Our Gilded Veins is not to be confined to the concert hall. “People have had to overcome a lot of adversity recently, so we’re also doing a bit of outreach with the concerto, going to Kibble [Education and Care Centre] in Paisley to work with people there. Opening other doors like this is so important for me when I’m working with new music. I want it to have a purpose beyond the concert hall.”

This is the second new concerto commissioned for Bryan and the RSNO. In 2017 she premiered Martin Suckling’s The White Road, described then in The Scotsman as “a sonic feast”.

“Jay’s is quite a theatrical piece. That’s important for me. We suffer as flute players from being typecast in this kind of pretty-pretty world, which I’ve never wanted to be part of. Music has to move people, have a purpose, give them something to talk about. This one certainly does.” Which means, of course, more people will be talking about Jay Capperauld.

Katherine Bryan premieres Jay Capperauld’s Our Gilded Veins with the RSNO at the Usher Hall, Edinburgh on 3 June, and Glasgow Royal Concert Hall on 4 June. Full details at www.rsno.org.uk