Join the national museum's high-tech revolution

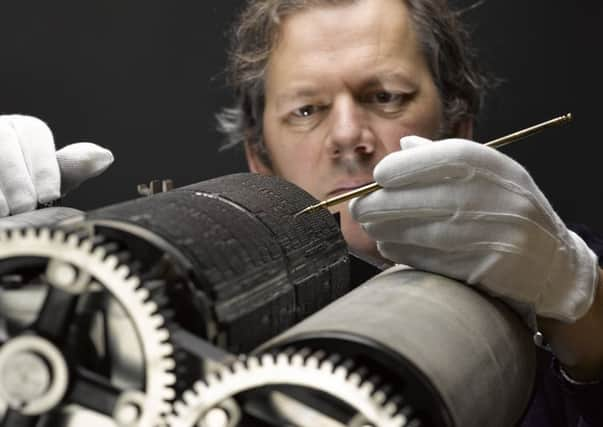

One of the centrepiece exhibits in the National Museum of Scotland’s ten new galleries is a working scale model of a Foster Printing Press. It is significant for many reasons – and not just because it’s a replica of the actual printing press upon which this very newspaper was once produced.

Standing a third of the size of the actual machine, which would have taken up vast amounts of space in the old Cockburn Street offices of The Scotsman in the 1880s, the model itself dates back to the same period. It has been painstakingly restored from the one originally built for the museum in its nascent Victorian incarnation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack then the museum was called The Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art. Part of its remit was to enlighten the public about the mechanics of progress with contemporary objects. The only way to do this at the peak of the industrial revolution – when machines were colossal feats of engineering – was for the museum’s own engineers to craft scale replicas from the original blueprints.

In the process of doing this, however, something else was born: the concept of interactivity. Many of the early models produced for the museum – the Foster Printing Press included – worked by pushing a button to make them go. With this simple idea, visitors ceased being passive consumers of exhibits. They became active participants.

It’s an idea that’s at the heart of the museum’s new galleries. With more than 3,000 objects displayed across six science and technology and four art and design galleries, the museum has introduced or updated over 130 interactive exhibits to enhance visitor engagement. These range from a Formula One simulator and a bionic hand to a virtual fashion wardrobe and an online game designed by Aardman Animations, the mavericks behind Wallace & Gromit. Meanwhile, digital labels – touch screens loaded with additional multimedia content such as filmed interviews and behind-the-scenes documentaries – contribute further layers of interpretation; a curated version of the kind of information that might be found online or in textbooks.

It’s an intriguing use of new technology. In the digital age, tactility is presumed to be a thing of the past, but in the museum the same technology that eliminates the need for physical copies of movies, newspapers, books and photographs has been harnessed to bring visitors closer to objects that would once have been forbiddingly displayed within a glass case or alongside a “Please don’t touch” sign.

The aforementioned bionic hand, for instance, is controlled via a touchscreen that also provides some backstory to its development. The significance of Dolly the Sheep – celebrating her 20th anniversary with a pride-of-place display in the new Explore gallery – is illustrated via a series of touch-screen displays and games exploring the advances in genetics since Dolly’s cloning and the questions and ethical issues scientists are now grappling with.

Then there’s the copper accelerating cavity from CERN’s Large Electron Positron Collider. The LEP Collider, which preceded the Large Hadron Collider, provided hints scientists thought might be the elusive Higgs boson. Displayed alongside the two-tonne copper cavity is a duplicate of Peter Higgs’s Nobel Prize medal and an interactive video interview that explains the complicated work being undertaken at CERN.

It’s all about bringing the past, present and future to life in ways that move beyond the outdated look-don’t-touch ethos. Physically interactive displays, like the electricity-generating treadmill in the Energise gallery, encourage visitors to be directly involved in the exhibits themselves. Touch-screen displays, on the other hand, provide additional context, helping generate a complete picture of the exhibit. In the Art of Living gallery, for instance, there stands a reconstructed 17th-century fireplace wall from the demolished Hamilton Palace. Audio-visual displays not only give details of this magnificent interior’s rich history (it was once owned by William Randolph Hearst, the American newspaper tycoon who inspired Citizen Kane), they show what the rest of the palace would have looked like.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ubiquity of digital technology in our daily lives is key to its prevalence in the new galleries. In the Enquire space, an interactive “virtual body scanner” which allows visitors to examine CT scans of people in various states of health, supplements biomedical exhibits tracing the evolution of medical imaging technology that has led to a greater understanding of what happens inside the body. Such innovative uses of interactive technology reflect the advances being made in the world today, much like the old working models did in the Victorian era.

The museum has also capitalised on our familiarity with interactive digital technology to make exhibits more readily accessible to those of all ages. In the Technology by Design gallery, kids and adults alike can get to grips with the principles of design, applying information from an exhibit tracing the development of the bicycle to a touch-screen game that lets them design a bike. Similarly, in the Energise gallery, there’s a game that helps visitors understand the basics of renewable energy by giving them an opportunity to design a wind farm. And for those interested in fashion, the Style Me touch-screen interactive lets visitors put together outfits from the museum’s displays and archives on a virtual catwalk.

A series of micro-sites, accessible via mobile devices, also lets visitors delve deeper into some of these exhibits, either by logging on to the museum’s wi-fi during a visit or getting online at home afterwards. And Gen, the game Aardman Animation has designed to complement the biomedical exhibits, is accessible anywhere via the museum’s website.

If this all sounds like the National Museum of Scotland is embracing the future, it is. But the Foster Printing Press exhibit remains a useful symbol. Technology may become obsolete, but our interaction with it continues to be fascinating.

• National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EH1 1JF, Open Daily 10:00 – 17:00. Admission free, Donations welcome. Find out more and buy tickets for exhibitions and events online at www.nms.ac.uk/Scotland