John Knox's bible '˜discovered' in Glasgow University archive

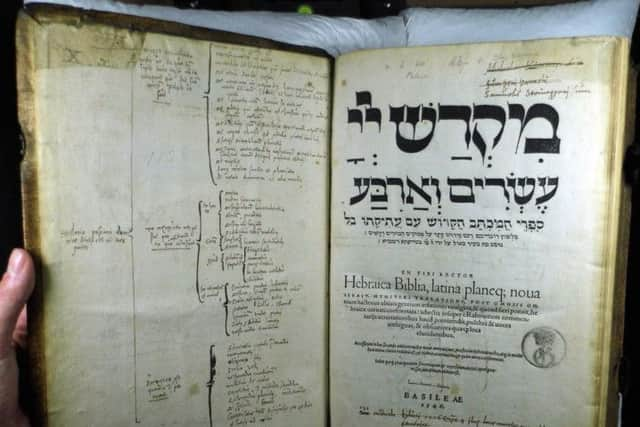

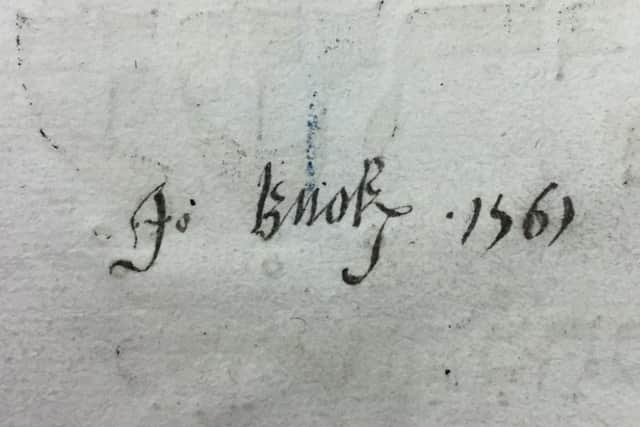

The large folio Old Testament, which was published in 1546 in Basel, Switzerland, appears to bear Knox’s signature dated 1561 on the reverse of the title page.

The Calvinist preacher, one of the leaders of the Scottish Reformation, was known to have amassed a large personal library during his lifetime - but only a handful of works directly linked to him have survived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe volume was bequeathed to the University of Glasgow in 1874 on the death of insurance broker and Bible collector William Euing as part of a remarkable collection of around 3,000 bibles - described at the time as “the most extensive and costly private collection (of bibles) ever formed”.

The ‘Knox’ Old Testament was purchased by Euing in 1864 from the London bookseller Ebenezer Palmer. A letter from Palmer pasted to the inside cover of the volume states: “The grand attraction... is that it has the handwriting and was the property of John Knox.”

Professor Jane Dawson of the University of Edinburgh, an authority on Knox’s life, believes the bible could well have belonged to the reformer.

“During his career and in common with most 16th century figures, Knox used a variety of different signatures and writing styles,” she said.

“In such a Latin/Hebrew Old Testament he would have probably used the Latin abbreviation ‘Jo.’ of his Christian name, Joannes. The spelling of Knox with a second ‘k’ would also be unusual for him, though this was a variant used by his contemporaries.

“The signature in the Old Testament is in a formal style and has more in common with the signatures Knox employed in his earlier days acting as a notary.

“This makes it appear quite different from the flowing ‘secretary’ hand he commonly used when writing in English or Scots in the early 1560s. Although there is no match with Knox’s known signatures, there is equally nothing to prevent this being Knox’s book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Knox had returned to Scotland in 1559 and would have been dependent upon the usual arrangement of a friend or agent purchasing the volume for him and sending it to Scotland.

“A packet of letters from Geneva including one from Calvin to Knox arrived in Scotland in the early summer of 1561 and it is conceivable this delivery might have included the Old Testament.”

Knox is considered the notional founder of Presbyterianism, which has today has millions of followers worldwide.

He died in Edinburgh in 1572.

Thomas Carlyle, the 19th century Scottish philosopher and historian, would later write: “This that Knox did for his Nation, I say, we may really call it a resurrection as from death… The people began to live: they needed first of all to do that, at what cost and costs soever.”