How US artist Jon Schueler fell in love with Mallaig

It is a perfect spring morning at Glasnacardoch, a mile south of Mallaig. From the door of Romasaig, a long, white-harled cottage and one-time schoolhouse, the view is sublime, across an inky Sound of Sleat to Skye’s Sleat peninsula and the dragon’s teeth of the Cuillin, still patchworked with snow, rising beyond. The sky, on this occasion at least, is iris blue, and hung with benignly drifting cumulus.

“This is where he would sit,” says Mary Gartshore, who now owns the house with her GP husband Iain. She gestures seaward: “Sky, sea, land. I love to sit in that corner myself.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMornings like this, she adds, make up for those days when you can hardly get the door open for the bludgeoning weather. Her neighbour, Donald MacDonald, agrees: “You’d have to know a bad day here; then you’d recognise Schueler’s painting.”

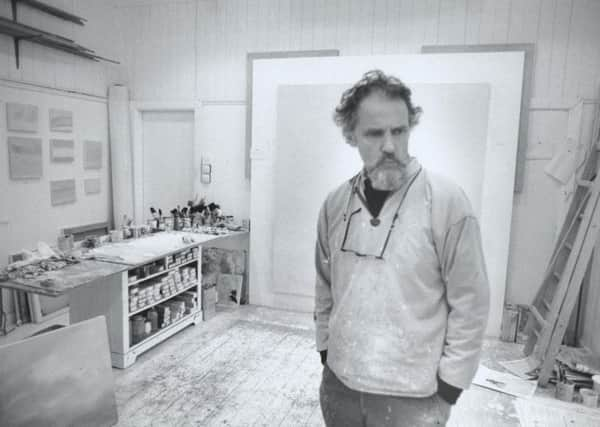

The artist to whom they’re referring is Jon Schueler who, although regarded as a member of the New York Abstract Expressionist school, from the late 1950s onwards consistently painted in Mallaig, whose turbulent skies informed his canvases, living at Romasaig for five years in the Seventies and returning most years until his death in 1992. Later this month, an international symposium at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the Gaelic college on Sleat, will celebrate his work, with exhibitions on either side of the Atlantic further marking the centenary.

“When I speak of nature, I’m speaking of the sky,” Schueler wrote in his powerfully candid memoir, The Sound of Sleat, “because in many ways the sky became nature to me. And when I think of the sky, I think of the Scottish sky over Mallaig…”

A different light pours through the windows of an airy loft studio perched high amid the Manhattan townscape. The spires of the Empire State and Chrysler buildings may glint a few blocks away, but the apartment is hung with canvases which fuse abstraction with luminous Hebridean skies.

The impact of these skies on Schueler’s painting cannot be over-emphasised, says Magda Salvesen, his widow and curator of his estate, who still lives on the 12th floor of the former factory building they moved into in 1977. “He never painted or drew outside during the time we were together, but every time he came back from Mallaig the images were still in his mind and in a way these canvases are every bit as Scottish as the ones he painted there,” says Salvesen, a slender Scotswoman whom Schueler first met in an Edinburgh street in 1970. Schueler was 53, she 25. In 1976 she became his fifth wife. Some of his previous marriages had lasted only a few months, but this one endured until his death.

Schueler was a driven character, she agrees, “but he wasn’t difficult to live with if you acknowledged his need to paint. When we arrived in Mallaig, I knew that the first thing he’d want to do would be to clean out his studio and get going. If you accepted that, it was easy. From 1976 I taught in New York, although he would have preferred me not to do that. Jon did have quite an ego and felt that instead of me being preoccupied with my students, he should be my only major project. But he was also extremely attractive and very vital. He read a lot and, as long as he had the space to paint, he was terrific company and had wonderful friends, like Alastair Reid [the poet and translator] and the artist Ken Dingwall.”

Milwaukee-born, Schueler graduated from the University of Wisconsin, tried journalism and later became an accomplished jazz bassist. He didn’t take up painting until he was 29, after the Second World War. He didn’t just paint skies; he had flown through them, as a navigator on Flying Fortresses in bombing raids over Europe, eventually being invalided out of the USAF with battle fatigue. Studying at the California Institute of Fine Arts, he was mentored by such influential Bay Area figures as Clyfford Still and Richard Diebenkorn. Moving to New York, he associated with cutting-edge painters like Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock and, exhibiting at the prestigious Stable and Castelli galleries, became regarded as one of the second wave of New York Abstract Expressionists.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLooking to Scotland as a place that might satisfy his quest to reconcile nature and abstraction, in 1957 he discovered Mallaig. He would return consistently, living there for five years from 1970, then most summers until his death in 1992, from complications relating to Parkinson’s disease.

“I went to Scotland to live inside my paintings,” he wrote, but he also needed challenge, going to sea with local fishermen. New York art critic Irving Sandler believed that “in Mallaig, Schueler found a physical landscape which matched his psychic one”. In 1981, Edinburgh University’s Talbot Rice Centre became both studio and exhibition space as he painted there for six weeks, the exhibition characteristically titled The Search. The centre’s then director, Scotsman art critic Duncan Macmillan, will be among participants in the symposium, as will Dingwall and Richard Demarco.

But why should his work be celebrated in a Gaelic college – albeit one perched spectacularly above his beloved Sound of Sleat? In fact, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig has run a Jon Schueler International Artist’s Residency for the past four years, hosting four artists out of 1,400 applications from across the world.

Donnie Munro, the college’s director of development, former singer with Runrig and a painter himself, first became aware of Schueler through the Talbot Rice show, as well as by talking to people like Will MacLean, the influential fisherman-artist (and another symposium delegate).

“I became fascinated in how Skye and Mallaig and the Sound of Sleat had been such a profound influence,” Munro explains. He contacted Salvesen, expressed interest and out of that emerged the residency, with help from the Schueler Trust. “When we became aware that 2016 would be Schueler’s centenary, we realised the possibility of bringing people together for an examination and reassessment of his work, internationally and with Scottish artists who might cite him as an influence.”

Under the convenership of Lindsay Blair, a Schueler expert from the University of the Highlands and Islands, the symposium is titled “The Sound of Sleat: Echoes, Reflections, and Transfigurations”. Associated exhibitions at Sabhal Mòr will display both work by Schueler and by incumbents of the residency established in his name, while, across the Sound, 12 fine Schuelers hang in Mallaig Heritage Centre.

As well as experts and artists from both sides of the Atlantic, the symposium will feature a discussion with members of the Mallaig fishing community, including local joiner Hamish Smith who, at 74, remembers Schueler fondly from the late 1950s when, as a 15-year-old, he used to carry wooden canvas stretchers up to the painter at his initial base, a scarcely weatherproof bungalow at Malaig Bheag just north of the town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I loved Jon. He was a great guy,” Smith tells me, adding that Schueler gave him two canvases which hang proudly in his home. “His paintings didn’t always mean a great deal to us when we were younger, but the number of times my wife and I stop and look up and say, ‘That’s a Jon Schueler sky...’ They all talk about a ‘Schueler sky’ here.”

• The Jon Schueler Centenary Symposium runs from 27-29 May. See www.smo.uhi.ac.uk. For details of centenary events, including exhibitions throughout Scotland, see www.jonschueler.com