How Scotland has been sold to tourists for more than 200 years

Back in 1775, James Boswell’s Journal Of A Tour To The Hebrides is credited with opening up the mysterious, far-flung northern corner of Britain to a wider audience.

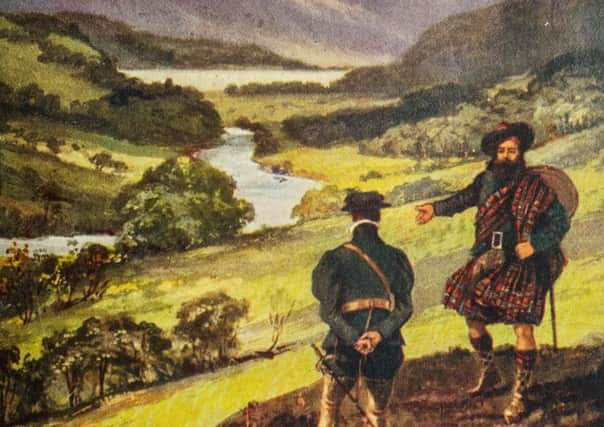

But it was Sir Walter Scott’s poem The Lady Of The Lake, published in 1810, that has been credited with single-handedly creating the Scottish tourist industry, now worth around £12 billion a year to the economy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore than 23,000 copies of the poem, set around Loch Katrine and the Trossachs, were sold – a literary phenomenon of its time. The work generated a sense of Scotland and the Highlands that was seized upon by writers and artists for years to come.

Rail companies were to harness this new-found interest in the pine-clad landscape with trips to Lady of the Lake country devised by companies such as the Caledonian Railway Company.

And with Queen Victoria choosing the Highlands and Royal Deeside as her preferred holiday destination, the scene for Scotland’s tourist industry was set.

While the version of Scotland championed by both the monarch and Scott has been widely derided for its saccharin take on Scottish culture and identity – particularly given that parts of the Highlands had undergone an often brutal dismantling of its culture – its potent tropes of tartan, bagpipes and sweeping landscapes as bywords for the Scottish experience endure to this day.

Dr Matthew Alexander, senior marketing lecturer and tourism specialist at Strathclyde University, said: “Sir Walter Scott certainly had a big role to play in the creation of Scotland as a tourist destination. Of course, you had The Lady Of The Lake, but he also engineered a royal visit of King George IV to Edinburgh, who emerged dressed in a tartan outfit worth around £100,000 in today’s money. He was terribly amused by Scotland and all things Scottish.”

“But the person with the biggest effect on Scotland as a destination is perhaps Queen Victoria. She writes in her diary that it is a place where she feels relaxed and left alone. Her influence was huge. If she sneezed in Pitlochry, Pitlochry would be the place to visit.”

There soon followed the “Victorian obsession” with Scotland, tartan and the hunting season, with rail stations such as Corrour and Rannoch built for those keen to stalk this new Royal-endorsed wilderness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

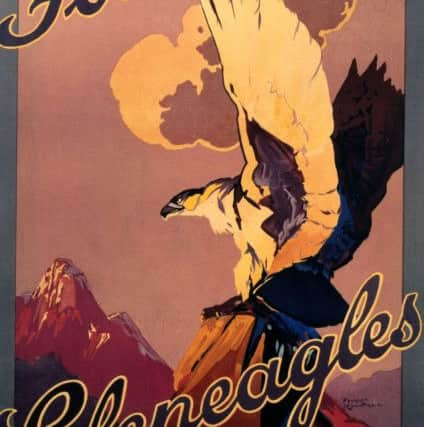

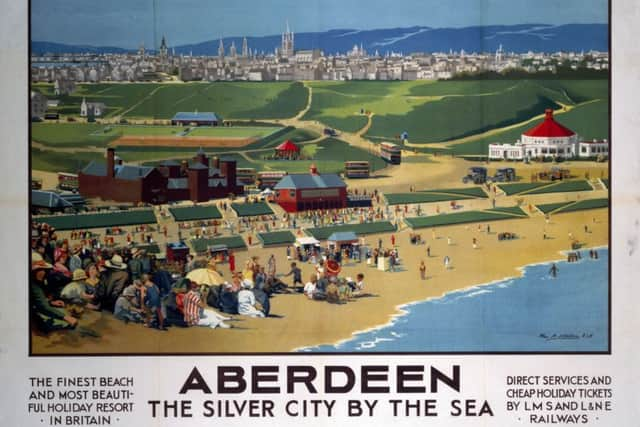

Hide AdEd Bartholomew, senior curator of railways and research at the National Railway Museum in York, said the rail companies of the day played “quite a role” in driving visitors to Scotland.

“The companies were not just promoting the journeys but the destinations themselves, to people living short distances away, but also to those from further afield,” he said.

“The advertising and marketing of the rail companies was particularly sophisticated in the 20th Century. They weren’t just printing posters, but also organising stunts for the Flying Scotsman and publishing guides to Scotland’s golf courses.

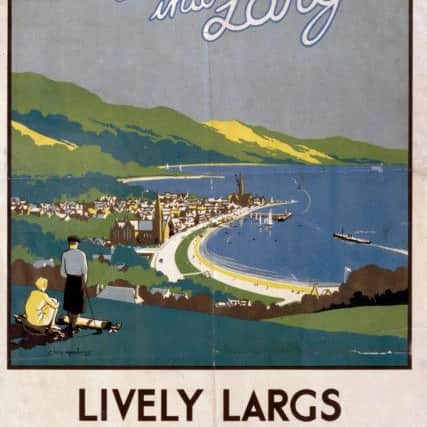

“If you lived in an industrial city, they would promote this idea that you could go for an excursion into the Trossachs, Loch Lomond or the Highlands. Later, some of the rail companies would develop their own steamers to take passengers ‘doon the watter’ for days away.” Posters for “Lively Largs” and “Sweet Rothesay Bay”, published by London Midland and Scottish Railway, were very much of their day during the inter-war years.

In the 1950s, as awareness grew of life on the Continent, Scottish seaside towns played to the long beaches and sea bathing on offer. One guide to Montrose – sometimes known as the Riviera of the North East – features a vivid graphic of two glamorous women in sun hats and swimsuits by the shore.

It reads: “In summer, the beach is an endless attraction. While the grown ups bathe and sun bathe, the youngsters paddle in the pools left behind by the tide.”

And to drive home the holiday feeling, it adds: “Father has his trousers turned up above his knees.”

The Scottish Tourist Board was set up in 1969 to develop tourism at a national level.