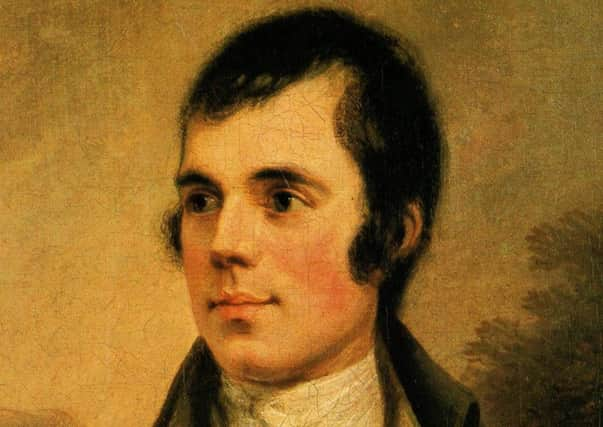

How Robert Burns died and his legacy examined

Burns’ legacy lives strong - and not just here in Scotland.

Every 25th of January - the Bard’s birthday - an increasing number of people both home and abroad take part in the celebrated Burns Supper, to enjoy haggis, whisky, and recitals of his work.

Centred around universal themes of nature and romance, his lyrics offer a timeless appeal which continue to resonate the world over.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis poem ‘Auld Land Syne’, which is famously sung around the globe on New Year’s Eve, is recognised by the Guinness Book of World Records as the third most popular song in the English language behind ‘Happy Birthday’ and ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’.

We’ve erected countless statues in his honour - Excluding religious figures Burns has more statues around the world than any figure living or dead save for Christopher Columbus and Queen Victoria.

And icons past and present from Michael Jackson and Abraham Lincoln to John Steinbeck and Bob Dylan have cited him as a huge influence. Dylan, in particular, described Burns in 2008 as his greatest inspiration.

The national coffers benefit too, with Burns contributing over £100 million to the Scottish economy every year.

Scotland owes the Bard a huge debt, but the great irony is that Robert Burns died owing money - £14 to be precise.

And despite his fame, we still don’t appear to agree on exactly what caused his death.

The popular theory goes that Burns died from rheumatism having been found by the roadside in the freezing, pouring rain after a heavy drinking session.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBurns’ reputation as a hard drinker would be hard to contest but the truth is that the poet had been seriously ill and for a long time.

He passed away at the age of just 37 on 21 July 1796, but had been suffering for at least five years before that.

In his 2008 book, ‘Robert Burns the Patriot Bard’, Patrick Scott Hogg claims that during the autumn of 1791 things were so desperate that Burns’ doctor came to visit him 5 times in one week. Robert was complaining of painful joints and fever - the early signals of rheumatism.

Within a few years Burns could barely get around without assistance. He was essentially an invalid, and while it’s true that he was no stranger to a glass of port, by 1796 trips to the local pub would have been out of the question.

According to Stewart Cameron of the Halifax Burns Club, the link with alcohol should be ruled out once and for all:

“Numerous authors have dutifully attributed Burns’ death to the effects of alcohol.

“Burns had certainly made himself unpopular for some of his libertine behaviour and revolutionary political views and there was likely no shortage of people willing to propagate the idea that he was ruined by drink.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is clear that Burns liked alcohol and was inebriated on numerous occasions. However, it is false to suggest that his drinking contributed to his demise. The symptoms strongly suggest he had terminal heart failure from bacterial endocarditis, as a complication of rheumatic fever.”