How North-East granite paved the streets of London

Aberdeen granite was considered the best in the world - a highly coveted material so hard wearing it could be used to build lighthouses in the North Sea, yet so fine it could be carved into highly ornate embellishments for new civic buildings and monuments across the UK.

Aberdeen itself became the stone’s biggest advertisement with the ‘Granite City’s’ imposing buildings such as Marischal College, the largest granite building in Europe, and the ornate homes of its more affluent residents proving to be fine endorsements of its qualities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt has been estimated that at least 50 per cent of Aberdeen’s buildings are built of stone pulled from Rubislaw Quarry in the west of the city.

“The granite industry emerged at the same time that the city of Aberdeen was modernising and developing. The two really are inseparable,” Jenny Brown, lead curator of history at Aberdeen Museums and Galleries, said.

She added: “The Granite City couldn’t have happened without the granite industry but the industry should really be seen as part of a much bigger picture.

“The industry really emerged as a proper industrial process at the end of the 1700s. This is a period when cities across the UK and other parts of the western world are creating a huge demand for paving and roads as they responded to their populations increasing in a huge way.”

The prosperity of the industry was sealed when in the 1760s when it was decided that granite from Aberdeen should be used to pave the streets of London.

Demand for the stone led to quarries opening up all over the north east, each known for slightly different colour and qualities with Red and Blue Peterhead just two examples.

During 1817 alone the quantity of stones exported to London was 22,167 tons. By then, rocks had already been sent south to build Waterloo Bridge, with granite from the Rubislaw Quarry supplying all 1,200 balusters for the bridge - each one cut and dressed by hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGranite from Rubislaw, which closed in 1971, was also ordered by the Admiralty to build new docks at Portsmouth. The Stevenson-built Bell Rock lighthouse near Arbroath was also built using the stone.

Despite its high reputation, the granite industry in the north east remained unforgiving and largely manual with gunpowder, crowbars and sledgehammers remaining the basic tools of the trade.

Early hydraulic tools were deployed in the larger quarries at the end of the 1800s but much of the work continued to be done manually, particularly at the smaller businesses.

Ms Brown described the “three man job” of drilling into the granite for dimension stone for use in larger scale projects.

She said: “This was exceptionally exhausting work. Someone would hold the metal drill while somebody would be striking it. Then the third person would turn it a quarter turn. This was of course hugely time consuming.”

She said the section of rock would be selected by a worker with a “trained eye” for identifying natural fault line in the rock, which made it easier to break off.

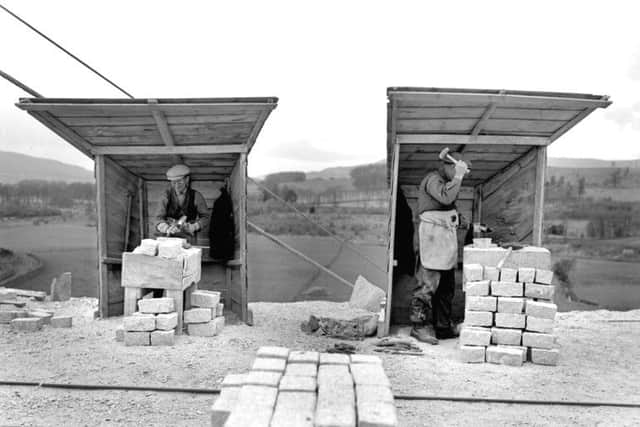

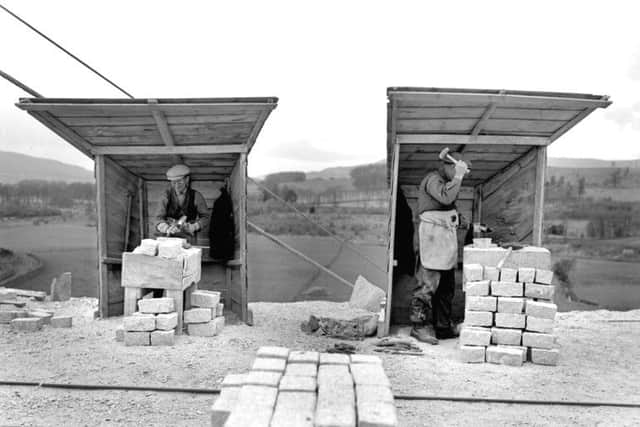

Another key job in the quarry was the making of granite setts or cassies, the blocks made for roads and pavements, which were small portable huts known as scathies dotted around the quarry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cassie maker would sit in small portable huts dotted around the quarry who would read the grain of the granite before cutting and cambering square stones to lay.

Granite was quarried in several other parts of Scotland, including Dumfries and Galloway and the west coast, with Europe’s biggest granite quarry still in operation at Glensanda near Oban.

But Aberdeen and the surrounding area thrived on its reputation as the most prolific granite producing area of the time.

Crucial to the expansion of the industry was Aberdeen’s access to the sea with thousands of tons of stone transported through its harbour.

Ms Brown said the industry hit its peak at the end of the 1800s, with a global export in tombstones part of its success.

Records show that 2,181 people were employed in the quarries in 1900, a relatively small workforce compared to fishing and textiles.

Ms Brown added: “It was a hugely influential industry and it carried with it this fantastic reputation for skilled craftsmanship and engineering expertise.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe success of the North East granite quarries was thwarted by new competition form the USA, which started to restrict imports of stone. Materials such as concrete and tarmac were becoming more popular.

New machinery was introduced to the North East and several quarries amalgamated but it was not enough to support the industry.

Rubislaw Quarry - described as thebiggest hole in Europe - closed in 1971 after more than 200 years in heavy production. By then the quarry was almost 140 metres deep. It is now under the ownership of a local businessman who has hopes to create a heritage centre at the site.

The quarry is said to still be a spectacular site, although it is largely now filled with water.

North east granite has not been used on a large scale for the past 30 years.

Granite will be used to clad part of the new Marischal Square shopping centre to mirror the grand college building opposite.

However, despite the city’s rich granite heritage, the stone will be imported from China for the job.DOWNLOAD THE SCOTSMAN APP ON ITUNES OR GOOGLE PLAY