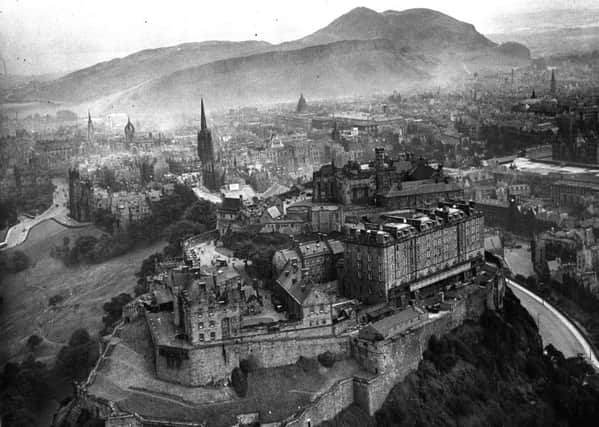

How fresh air replaced '˜Auld Reekie's' suffocating smog

Local geography and climate mean that what goes up in Edinburgh generally comes down in Edinburgh, as pollution.

Whether traffic fumes or smoke from coal fires, the meterological effect called inversion means that it is liable to be trapped in a low-level blanket of air uncomfortably close to ground level.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Auld Reekie’s problems or air pollution reflect periods of widespread social change affecting every city in the western world.

The dramatic growth in car ownership has been just one expression of an increasingly affluent society.

To this day, politicians seem reluctant to take draconian measures to curb the main cause of air pollution.

It wasn’t that way with smoke. For unlike the mainly invisible cocktail of exhaust gases that contaminate city air, smoke pollution was all too visible.

Smoke pollution levels in Edinburgh of the 1930s were found in tests to be an amazing 1000 times worse than now.

The Capital of the past had smoke puffing from every chimney, from homes, factories and incinerators.

Cities like Edinburgh were blanketed by a dense yellow fog during winters, the unhealthy shrouds being created by the build-up of smoke and sulphur dioxide in the still, cold air.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSulphur is found naturally in coal and sulphur dioxide is produced when it is burned.

The fogs it helped to produce were later to become known as smog. But it was a problem cities simply learned to live with for many years.

That is until a single, shocking incident which stunned the public and forced Parliament to act.

It was in December 1952 that a thick smog built up over London, bringing transport to a stop throughout the city. Increasingly, as the smog persisted, people suffering from bronchitis and heart disease reported to their doctors. There were to be 4000 deaths attributed to the smog - and national action was now inevitable.

The Clean Air Act of 1956 would control emissions from industrial premises and help create Smoke Control Areas for the first time.

The importance of household fires throughout Edinburgh and elsewhere was that the smoke was composed of particles of carbon or soot plus tiny particles of tar and hydrocarbons.

Particles were much finer in smoke from household coal than from factory chimneys, making them easier to breathe into the lungs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd household fires were only about 30 per cent efficient. The less efficient a fuel, the more smoke it produced.

Although acid rain was not identified then as major problem, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides from coal burning were all the time being sent into the atmosphere.

But in Edinburgh at least, a dramatic change began in 1957. It all started in Sighthill. Cramond and Corstorphine followed, and gradually the smokeless zone extended across the western half of the city.

The logic was that Edinburgh’s prevailing wind came from the west, so improvements in the west would improve the whole city. Archive images taken by a ‘News’ photographers show that the improvement didn’t come overnight however.

The city’s smoke monitoring machine in Johnston Terrace showed a reading the same day of 170 micrograms of smoke and 171 micrograms of sulphur dioxide per cubic metre.

Fifteen years later the reading was to be 13 for smoke and 42 for sulphur dioxide. By 1985, about half the city’s 185,000 homes were within smokeless zones.

The clean-up was being helped by families everywhere choosing to use cleaner gas and electricity or smokeless fuel for heating.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnvironmental health officials reported a fall in city figures for bronchitis and related illness and Auld Reekie enjoyed more hours of sunshine.

By 1987 more than 100,000 homes were in smokeless zones and Marchmont and Inverleith were targeted as the next areas for change, followed by Mayfield, Alnwickhill and Kaimes.

But concern was expressed that things were moving too slowly as the target year for a smoke-free city - 1992 - drew near.

Funding problems were blamed. But at last, in 1991, the council announced they were going all out to finish the job by 1995, using the biggest smoke control order by a British local authority to clean up the city’s entire east side, making virtually the whole Capital a smokeless zone.

As one colourful local coal merchant said of areas still burning coal: “It will become like malt whisky. You will use coal only when guests come for dinner.”

Roll on 2040 and the ban of petrol and diesel cars.

• This article is a revision of a piece first published by the Edinburgh Evening News in 1992