A history of Cultybraggan: Scotland's POW camp

The village’s historic conservation title reflects its surrounding beauty and rich history, becoming wedged in the past for preservation and flung to the future for necessity, somehow finding the all important balance between the two. Doing what many places have failed to do, in keeping the past present.

In the midst of all this beauty, is the Comrie Development Trust, an organisation determined to keep its community thriving and as self sufficient as possible. The busy village with a population of only 3,000, plays host to over 50 different community groups. The trust have become testament to many other organisations in Scotland trying to do the same, which is an inspiration to the cause of development in its own terms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

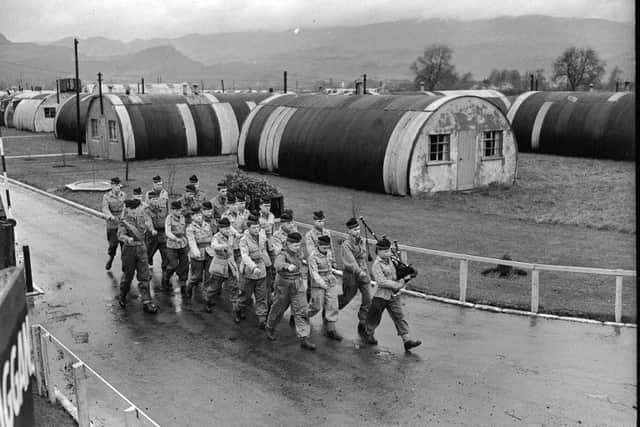

Hide AdIn 2007, the CDT bought Cultybraggan camp with the intention of turning it into a sustainable and educational tourist attraction. The huts that line the camp were built out of corrugated iron to hold the influx of prisoners, who had been captured and relocated to Britain during the Second World War.

Nissen huts, named after the founder, Peter Norman Nissen, were common in PoW camps across Britain but were only supposed to be temporary. However, they have stayed the same ever since, having been lived in and used for more than 70 years.

But growth for the camp has proved hard, being faced with many constraints. Refurbishing just one of these Nissen huts is estimated to cost up to £40,000 - and there is an approximate total of 90 all together - with a number of these listed as significantly important by Historic Scotland.

Thankfully as a country Britain goes to great lengths in preserving our history. We thrive on remembering, a nostalgia of what once was and by learning through the preservation of our past, mistakes and all, it marks an example for our future.

Fiona Davidson, originally from Edinburgh, moved to Comrie to bring up her children over 20 years ago. She now works as a volunteer for the Comrie Heritage Group - a integral part of the CDT, in a place so focused on historic relevance. We discussed Cultybraggan camp’s past, present and future as we met for a tour around the camp on a gloriously blue, and brisk morning.

The story truly began in the midst of the Second World War, when prisoner of war camps were cropping up all over Britain. In 1941, the army acquired land from the nearby Cultybraggan Farm, adopting the namesake. It later accumulated several others such as ‘Camp 21’ or the ‘black camp of the North’, when it became well known for holding some of the most dangerous war criminals captured during the Second World War.

Life on camp was as expected, every prisoner defined on a scale of threat to the camp and other prisoners. The scale ranged from white to black, with each PoW being assigned into their appropriate area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe whites were considered the least threatening, with some bearing special passes to work in the neighbouring farms. The greys were a risk, and the blacks were considered the most dangerous.

The camp purposely positioned Polish soldiers as guards, to man the 4,000 men as a deterrent to misbehaviour, as they hated the Germans for invading their country. Although this was not a complete deterrant, with the camp reporting at least one murder and several attempted escapes.

After the war was over, men were put through a so called “de-Nazification” program before they were allowed to return home.

There was a stigma that these camps were horrific on levels with the imfomous enemy PoW camps - and while this would of been true to those who misbehaved - the reality was, at least in Cultybraggan, that it was a more liberal prison life.

The men had the option of joining choir, orchestra, learning English as well as a number of other activities - the view was held that at the end of the day, most of the soldiers were young men who had very little chioce in going to war.

Some of the original prisoners even came back to revisit the camp, Fiona said: “One of the guys turned up to one of our open days, he was an old man, very small.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He came up to us and he said: ‘Excuse me, my name is Ernst Krebs. I spent my 21st birthday here as a prisoner of war.’

“There was also a German re-enactment group that were visiting at the same time. Mr Krebs was standing a bit away from him but when they came up the path, the first thing he did was salute.

“He saw people in the uniforms and it was an automatic reation to salute to men in those uniforms.

“I got hairs on the back of my head watching it. Mr Krebs said that he had arrived at night and when he woke up in the morning and came out one of the Nissen huts that he slept in, and he seen the view. He thought he was in heaven, it was the most wonderful thing he had seen.”

The Military of Defence took over the site in the 1950s, preserving the majority of its original structure.

The most significant change to the camp came in the 1970s when a large section was demolished to make way for an assault course and firing range.

Now the view is quite different, with trees in their infancy criss-crossing the landscape beside the crumbling walls of the barricades.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust across from it is a popular spot of community allotments.

Several years ago, a community share scheme was set up to invest in the camps latest project. To create ten self-catering huts for tourists to stay in, retaining the original structure as much as possible. The plan is to raise more funds through this project, so that it will allow for future infrastructure works, and other things that grow the community, such as connecting the village and the camp through a series of trails and cycle paths.

With 63 per cent of the local population supplying the £27, 235 that was raised. Their investment is just as important to the people down the road as it is to our heritage.

Fiona understands this being a local herself, saying that: “In 2004, the Ministry of Defence decided to vacate, and we were quite concerned that it was going to be like, either a big housing development or something that maybe would be detrimental to the village, or the village couldn’t support it with the infrastructure. So through the Comrie Development Trust, the village bought Cultybraggan camp with different loans and funding. We then had to think how to pay the loans back and how we could make the camp work.”

So the investment led to smart decision making - ways for this to help the community and its local economy. It was split into four quadrants, the self-catering quadrant, a work in slow progress, the commercial quadrant, with the units already sold to local businesses.

Opposite this, through the lining of the guard huts and water towers, is the food quadrant, where the newest of the buildings sit. Once the old MoD cafeteria, it is now home to a catering company. It is on this building that you see the PV panels for solar energy installed, and with these running at 10kW, the trust have plans to expand its solar energy reliance as time goes on. Sustainability is key for them.

Along from this is the beautifully arranged orchards and allotments, a nod to its progress in creating biodiversity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs we get further into the camp, Fiona shows how two lines of the Nissen huts have been transformed for local businesses.

The trust having gathered permission, took out the original door frames and expanded them. This marks the quadrant opposite the decommissioned bunker, and calls home to many local businesses who use the specialised rental scheme through the CDT - one that offers low rent in exchange for maintenance and care.

Cars from a past business lay rusting under the sun. Fiona sighs, and moves us on, saying that the owners did a runner without paying some of the money owed. When they do so much for the community it is hard to see their efforts tarnished.

Heading back towards the ‘spine road’, which is the main road leading into, and connecting most of the camp. We pass by a Nissen hut with brownie paraphernalia lining the windows. Fiona points out that the brownies use this during the summer months as their camp base. Opposite this is the old marching ground, with future plans in place for it to become sporting facilities. The camp is now a home for a new generation of people in a very different way, and this is what the trust want for its future - regeneration for a new generation.

We stop by one of the longer Nissen huts that dot the camp in each direction, these were once sleeping huts and would of held around 90 men .We enter, and it is colder inside then out, our voices echoing in the chill of the past. Fiona explains that one day this could become filled with its original bunk bed structure for primary and secondary children of education to stay in, as part of an educational experience.

There is so much planned, yet it is not an easy process.

Right now, the trust wait patiently for funding to continue on with the self-catering business and the old mess hall as a community style hub. Though it is a good investment, groups who supply funding have a very long process to make certain the funds will be used correctly, a common resistance in a financially wobbly economy. Currently, the trust are in their second consultation with the Heritage Lottery Fund, and it is so important that they get it, as Historic Scotland are planning to match whatever they decide upon to get the self-catering units up and running. After a wait of nine years, it is crucial they can finally begin to operate as a tourist attraction they so deserve to be.