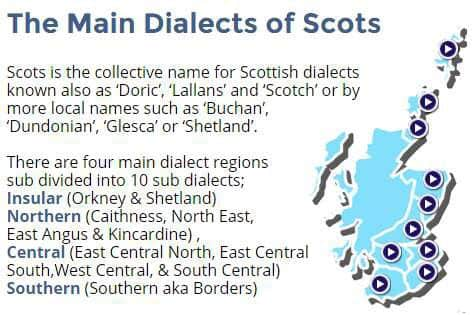

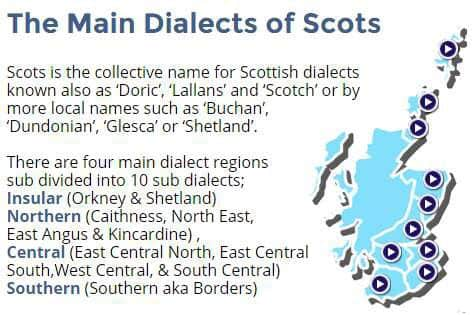

A guide to the dialects and words of Scotland's regions

‘Insular’ dialects hail from the remote communities of Orkney and Shetland, making for one of the most colourful dialects still in use. Northern dialects such as Doric are in action across Caithness, the North-east, Kincardine and Eastern Angus, while Central dialects also have their own geographical permutations.

Finally, Southern Scotland is influenced by both its neighbours to the south and north, according to the Scots Language Centre), which seeks to preserve and maintain Scots dialects in contemporary society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Robert McCall Millar is Chair in Linguistics and Scottish Language at the University of Aberdeen. He said: “It’s almost inevitable that will be differences between the urban and rural dialects of Scotland. Until 200 years ago, the fastest method of getting between areas was walking, so people did not move much.

This is why areas such as Laurencekirk and Stonehaven in Aberdeenshire, though only 10 minutes apart by road, have little differences in their dialect.

“Urban areas have also seen bigger changes in social identity, with almost all seeing net migration and the spread of new words into different areas over time.” READ MORE: {http://www.scotsman.com/news/education/minority-languages-like-gaelic-good-for-the-brain-1-4030379

North and Highlands

From Caithness down to the Black Isle, the Northern dialect share similarities with Doric in the North-east of Scotland. For example, both use “f” instead of a “wh”. Also, the “th” at the start of many words is lost so that “the, that, this and they” are pronounced “e, at, is and ey”.

It is also common for the sound ee to replace a number of vowels such as ai, oo and u in words such as been-bone, heer-hair and meen-moon.

Shetland and Orkney

The Shetland dialect is a mix of the Scots dialect brought to the islands by lowlanders at the end of the 15th century and Norn, the Scandinavian language spoken there from approximately 800AD to the middle of the 18th century.

Key features include the use of “to be” instead of “to have” as an auxiliary verb (“I’m written” as opposed to “I’ve written”) and the use of the word “thoo” or “do” for “you”, and “dat” or “at” for “that”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTypical phrases and words from Shetland include ‘Fin his breeks a burden’ (to find a task too difficult) and ‘Up in her cuddy’ (to be in high spirits).

Like Shetland, the Orcadian dialect owes much to Norwegian. Orkney dialect differs from Shetland in that Shetland follows Nordic stress patterns whereas Orkney has a rising intonation akin to Welsh or Irish. Tricky or misleading pronounciations wait to trip up the unfamiliar, including ‘Blide’, meaning ‘happy’ or ‘pleased’ and pronounced as ‘blyth’.

Orkney words: Koad – pillow; Dilder – shake, jostle “He dildered the bern aboot on his knee afore bed”; Sprett – split or burst – “Ah’m geen an sprett the erse o me breeks!”; Blide – (pronounced blyth) – happy, pleased

Shetland words: Aetin da bread o idlesaet – Lolling around doing nothing; Peerie – small; Tane fornenst da tidder – one against the other; Soothmouther – anyone not from Shetland.

North East(Doric)

Covering the area down to Kincardineshire, the Doric dialect is firmly rooted in the agricultural communities it serves. Celebrated in its own festival, its most notable features are, as in the North, the use of “f” rather than “wh”; “a” before “n” sometimes becomes “ee” – so ane (or yin) is een, nane is neen, lane is leen and so on.

Memorable words from the region include ‘stewie-bap’ for a flour roll and ‘Fairfochen’, meaning ‘exhausted’. Words: Cappie – ice-cream cone; Ficher – play with your fingers; Fooge – play truant; Hallach, halliket or hallyrackit – obstreperous; Stewie-bap – floury roll; Louns and quines – lads and lassies. Dookers – swimsuit; Fairfochen – exhausted.

Tayside and Central

The Angus, Perthshire, Lothian and Fife areas have a high concentration of dialects spread across the regions. Whle you’re there, you’re likely to hear terms as diverse as ‘Baffles’ (slippers), ‘Foggie bummer’ (bumblebee) and ‘Clash bag’ (for a gossipy person).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDundonians are known for the “eh” sound in their speech, such as ‘Kettle-biler’ for an unemployed man (dating back from the time of jute mill) or ‘ingins’ for onions.

Words: Baffies – slippers; Cundie – drain; Punders – underpants; Moich – disgusting; Tekel – awesome; Dub – puddle

West Central

With areas such as Dumbarton, Renfrew, Lanark and North Ayrshire utilising their own dialect, the language of the area was split between city and non-city areas in the 20th century.

In North Ayrshire and Lanark, people continue to use traditional Scots words such as awa, braw, ken, nicht, muckle (away, fine, know, night, great/much) and, throughout the region, forms such as abin, gid, shae, pair and yin (above, good, shoe, poor and one) are commonplace.

Words: Tawnle – bonfire; Cludgie – toilet; Ginger – any fizzy drink; Lumber – date; Wean – child; stoat-up – when in a football the match is restarting after the ref has stopped for an injury and the ball is bounced between players of the opposing sides; Gallus – self-confident to the point of cheeky.

South West

The communities of South Ayrshire, Kirkcudbright, Wigtown and Dumfries and Galloway are influenced by West Central areas as well as Irish migrants.

Most of the region uses dialect speakers use pronunciations such as “gyid, min, shin” (good, moon, shoes). It is common to hear certain things in the dialect contracted in speech. For example, “in the”, “on the”, and “at the” become i’e, o’e, etc, as for example i’e toun or i’e mornin (in the town and in the morning).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWords: Crowbogle – a scarecrow; Jawhole – a drain; Ken – you know; Ha neck – how embarrassing; Mintit – something good; Funnered – full up; Speir – inquire

Borders

Whereas most speakers of Scots would say “you”, a person from this region would say “yow”. They say now and down rather than “noo” and “doon”. In Hawick, people traditionally spoke a distinct dialect known as Teri talk.

Terms unique to the area include ‘Watergaw’ (a rainbow on the verge of disappearing) and ‘Fooky-meat’ (a pastry).

Words: Emmock – ant; Mauckie – bluebottle; Shive – slice (as in bread); Watergaw – a rainbow on the point of disappearing; Splairgit – spattered; Fooky-meat – a pastry; Yett – gate; Steek – shut

Glasgow and Edinburgh

Glasgow’s ‘patter’ was made famous by Rab C Nesbitt and Chewin’ the Fat, amongst others. Common words include ‘clatty’ for dirty and ‘scunnered’ for exhausted.

Edinburgh, on the other hand, sees its dialect largely influenced by the Romany language. To call someone a ‘radge’ is to call them mad, while to ‘take a deek’ is to have a look at something.

Glasgow words: Clatty – dirty; Hoachin – full; Ya dancer – that’s great; Mingin – disgusting; Scunnered – exhausted; Coupon – face; Bahookie – bum; Pure – really. Edibburgh words: Radge – a mad person; Barry – good/fantastic; Chorie – steal; Lowie – money; Deek – look; Likesay - you know; Scoobied – clueless; to tan – to consume (as in “I tanned ten beers last night”)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMichael Hance, Director of the Scottish Language Centre, said: “From Shetland to Stranraer anyone travelling round Scotland can hear the many different voices that make up our linguistic landscape.

“Dialects give language local colour, they are markers of identity and are one of the main components of the soundscape of any region.

“We are lucky in Scotland to possess such linguistic wealth, and we will continue to do everything possible to keep our dialects alive.”