The Glasgow woman who laced her lover's cocoa with arsenic

Life could have panned out very differently for Madeleine Smith.

Accused in 1857 of poisoning her lover, Pierre Emile L’Angelier, to death - and with a clear motive to do so - the authorities could have very easily thrown the key away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut instead she got away Scot-free. Opinion remains divided over her innocence to this day.

A secret love affair

Madeleine and Emile made an unlikely pairing. She was just 20 years old from a prosperous, middle-class Glasgow family. He was a working professional hailing from the Channel Islands, and ten years her senior.

First introduced to one another thanks to one of Miss Smith’s neighbours, the couple embarked on a clandestine love affair in 1855.

The two soon formed a close bond, meeting frequently at Madeleine’s home at 7 Blythswood Square while her family and servants slept.

Both Madeleine and Emile would communicate in secret by letter. L’angelier hand delivering his through Madeleine’s bedroom window, while she used the local postal service.

As time progressed, the tone of the letters - many of which have been preserved - became increasingly steamy, revealing the kind of intimate details about the relationship which would have shocked Miss Smith’s family.

In his later letters, L’Angelier makes his intentions to marry Smith quite clear. Smith, in turn, starts to refer to herself as L’Angelier’s ‘darling wife’. The couple even become engaged.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut at no point, however, was Smith under any illusions - she was well aware her family would never approve of such a match.

The waters were muddied further when, in January 1857, Madeleine’s family approved a marriage proposal for her from a neighbour, William Minnoch.

Madeleine’s sudden ‘arranged’ marriage changed everything.

L’Angelier was swiftly given the old heave-ho, and frenzied, but unsuccessful attempts, were made by Madeleine to retrieve the passion-laden mail she had sent to his address. In a bid to convince L’Angelier to return them, Madeleine writes: “I trust your honour as a gentleman that you will not reveal anything that may have passed between us.”

To her dismay, L’Angelier refused to play ball, threatening instead to forward the letters to her father if Madeleine didn’t marry him.

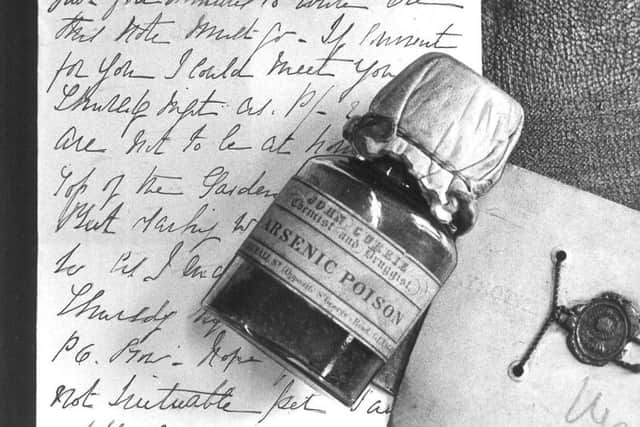

But within just twelve weeks, Emile L’Angelier was dead. The coroner later revealing that enormous amounts of arsenic had been found in his stomach.

The police then discovered Madeleine’s love letters, and in a subsequent raid on her family home, found proof that she had recently purchased quantities of arsenic from a local chemist. Madeleine Smith was arrested and charged with murder.

The trial

In July 1857, Madeleine Smith’s trial at the High Court in Edinburgh commenced.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe court heard how L’Angelier had spent two months battling against an unknown ailment.

Ann Jenkin’s, the deceased’s landlady, revealed how one February morning L’Angelier had been vomiting uncontrollably and was complaining of an extreme thirst. His complexion at this time was described as a pale, deathly yellow.

The indictment charged Miss Smith with having issued arsenic to her lover on several occasions between 22 February and 22 March. The latter causing his death just one day later.

L’Angelier had unwittingly ingested the deadly poison in spiked cups of cocoa which Madeleine had allegedly served him from her own home.

Throughout the trial, Smith was described as bearing a “sadness in her expression, but no trace of that anxiety and deep mental suffering to be expected in a woman charged with such a dreadful crime and with her life in such imminent danger”.

After a short recess on the eighth day of the trial, the jury resumed court proceedings to return a shock verdict of not proven.

It was concluded that there simply wasn’t enough evidence to convict Madeleine Smith of murder or even intent to commit it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMadeleine, who had spent much of the preceding days looking quite emotionless and vacant, was said to have cracked a brief smile upon hearing the news. She had steadfastly maintained her innocence throughout and had pleaded not guilty.

As the result was announced, bedlam ensued in the courtroom, as one attendee recalled: “The announcement was received with a tremendous burst of applause which last several minutes. The judge became extremely angry and shouted out, ‘Officer, bring that man before me’.

“Everybody seemed to be making a row, but the policeman seized a harmless-looking young man, who did not seem to me to have taken part in the applause at all, and thrust him into the dock.”

Despite the court being unable to prove her guilt, Madeleine Smith, was unable to shake off the notoriety of being directly involved in such a high profile case, and she struggled to slip back in to her old life.

Smith changed her first name to Lena and relocated to London, eventually settling down to marry Pre-Raphaelite painter, George Wardle.

The marriage did not last, though, and Smith moved again, this time to the USA where she married for a second time.

With most in her home country having assumed that Madeleine had long since passed away, a 1926 Scotsman newspaper report sensationally revealed that this was not the case.

In April 1928 Madeleine Smith died in New York state under the name of Lena Wardle Sheehy at the ripe old age of 93.