The extraordinary story of the Dundee whaler who joined the Inuits

The papers, found rolled up in a drawer in the family home just over a year ago, reveal one man’s 18-month odyssey through disaster, hunger and near-death amid nature’s most extreme elements.

Also revealed is Ritchie’s high regard of the natives for their hunting and survival skills - as well as the kindness they showed him as he immersed himself in their way of life after becoming stranded in the frozen reaches of the Canadian eastern Arctic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRitchie, a teetotaller from Gourdon in Aberdeenshire, recalled how he temporarily took the Snowdrop’s wheel leaving Dundee on April 9 1908 given the drunkenness of all men on board - from the captain to the cook.

For much of the 19th century, Dundee was the European capital of the whaling industry, bringing in up to £150,000 pounds a year.

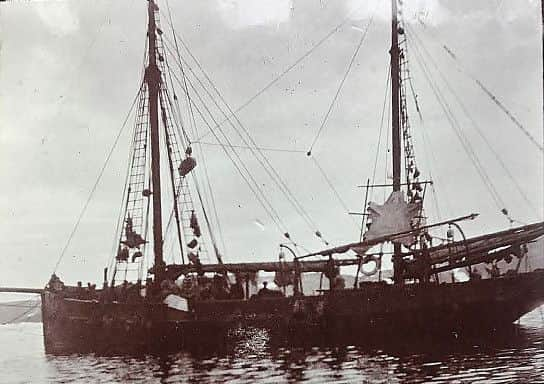

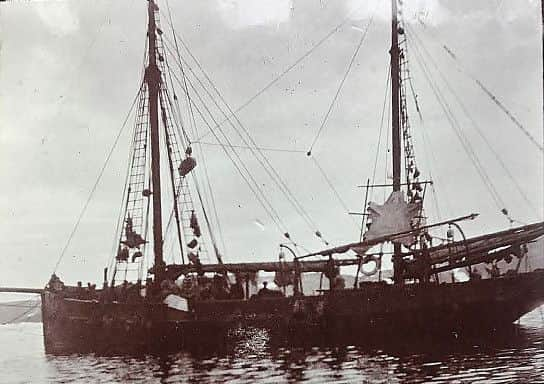

As many as 15 ships sailed from Dundee to the Arctic at the beginning of every year, returning home in the autumn largely loaded with whale oil, used in lighting and in processing jute, whalebone for ladies’ corsets and sealskins and other furs for gloves and hats.

As the voyage of the Snowdrop continued, 65 native men, women and children were collected from an Inuit settlement on the Davis Straits to hunt for the ship’s owner, Osbert Clare Forsyth-Grant of Ecclesgreig Castle, St Cyrus.

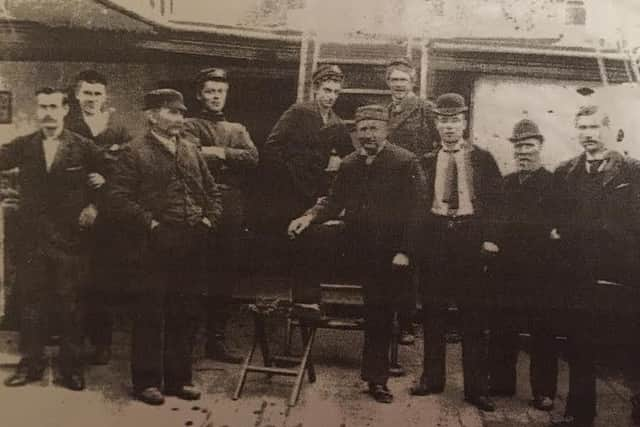

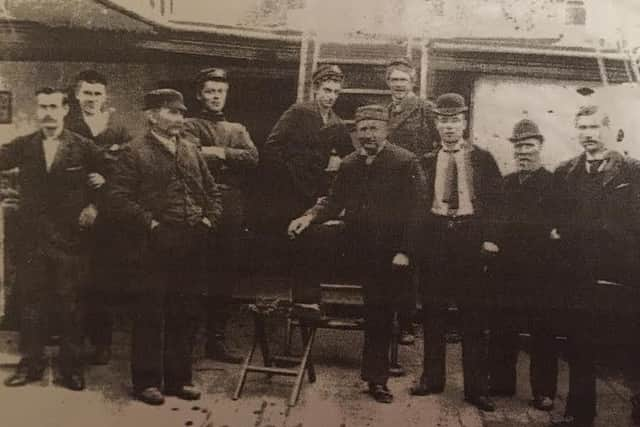

The mission had broadly been a success with “650 walrus, 600 seals and a great many bears” on board - with Ritchie noting the “great help” of the natives to the 10 Scots on board.

But as The Snowdrop prepared for its return home, the wind started to “blow very heavy from the eastward” and the anchor started to drag. The engine failed and the whaler was on the rocks.

Ritchie led the rescue of the crew after struggling ashore with a rope to fix the ship to a big boulder.

READ MORE:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We got everybody, old and young ashore, and did not lose nor hurt anyone. We lost everything we had. The only things I saved being my Bible, and a pair of socks and mittens,” he said.

“Well, we were all thankful for our escape, but we had nowhere to go for shelter until some of the sails washed ashore.”

Ritchie recalled how they were able to eat tins of food that had bobbed up from the store with the Eskimos also lighting fires from the blubber that had been on board.

After managing to retrieve a smaller vessel from the water once the storm had passed, Ritchie embarked on a voyage north with four Scots and a native guide to the Frobisher Straits with a hope of intercepting another Dundee whaling boat - Active - known to be in the area.

After seven days on the move, the guide refused to go any further due to the weather.

By the time they had returned to the site of The Snowdrop wreck, the ship had completely broken up - with the Eskimos on the move home to Signai -or Cape Haven - around 90 miles away.

Ritchie embarked on another five-day mission on foot to find them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When we arrived, all the Eskimos were glad to see us,” he recalled.

Despite seven tonnes of meat and blubber earlier deposited at the whaling station “our owner would not give us anything, so we had to depend on what the Eskimo could give us for food,” Ritchie said.

“It was very hard at first to get used to eating raw seal flesh.

“Sometimes they boiled it in a tin, but they said raw flesh was best so we just had to do as they did and be thankful.”

Ritchie became known as Kivvy Actow amongst his Inuit friends and was given the name after fighting his way out of a 9ft ice flow.

He had plunged through soft snow into the water while out hunting for seals in fading light.

“When the Eskimos saw me and heard my story, they were amazed. They took off my frozen clothes and rubbed all my body to get warmth and circulation,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was not long before Ritchie was on the move again, in November 1908, as he tried to reach Hudson Bay with five crewmates.

They moved with the Eskimos who were trying to get back home for winter, the Scots hopeful of finding the Active.

Three months later, they were still travelling. Ritchie decided to leave behind his companions and venture forth with two new families of natives who offered to take him to Hudson Bay.

A baby cub, born to a bear shot by the group, was to join them on their journey.

But Ritchie’s records how his adventure starts to take his toll. Weary and tired, he falls behind the convoy. He would lie on the ice to rest and move when he got cold.

“I lay down thinking it was all over. I thought what a struggle I have had, and how I was going to die or be frozen to death. Well, I prayed I might be saved.”

Two Eskimos with seven dogs and a sledge returned to Ritchie - and he survived once again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the final leg of his journey Ritchie fell unconscious, the Eskimos telling how he “lay for 21 sleeps and did not know anything.”

In June, having lived on walrus and seal skin, Ritchie finally met The Active, anchored on the islands not far from a glacier where he had briefly settled.

“When I got on board, I saw three men who were shipmates on the Snowdrop, and not one recognised me.”

He recalled how his crewmate Jimmy Scott turned away after shaking his hand, unaware of who he had just met. Realising his mistake, he ran to fetch the Captain.

Ritchie recalled: “Captain Murray said, “Jimmy, you have made a mistake - I don’t see a white man”.

“So Scott pointed to me. Captain Murray came over and said “Are you a white man?”

“I said ‘yes’. Then I always remembered what he said to me...’what a sight’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRitchie and his crewmates returned to Scotland on a liner called Siberian, which landed in Glasgow in November 1909.

He recovered from this ordeal and resumed fishing in Gourdon on his boat Happy Ending I.

But one thing was never to leave Ritchie following his time in the Arctic.

“I have never forgotten the kindness of those Eskimo people, all my life,” he said.

He later bought into Happy Ending II with his brother James, who was captured by a German U-boat off the Aberdeenshire coast and sent to a PoW camp for almost three years.

DOWNLOAD THE SCOTSMAN APP ON ITUNES OR GOOGLE PLAY