Edinburgh Art Festival reviews: Roger Fenton | Josef Koudelka | Douglas Gordon | New Edition | Fault Lines

Shadows of War: Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, 1855 Queen’s Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Josef Koudelka: The Making of Landscape Signet Library, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDouglas Gordon: Black Burns Scottish National Portrait Gallery **

New Edition Edinburgh Printmakers **

Fault Lines Patriothall Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Cardigans, balaclavas, Florence Nightingale and the Charge of the Light Brigade are about all the Crimean War has left in our collective consciousness. Fought from 1853 to 1856 by the British, French and Turks against the Russians, in some senses it’s still going on. British commander-in-chief, Lord Cardigan, gave his name to the eponymous garment. The balaclava remembers Balaklava, the British base during the siege of Sebastopol, the main focus of the war. But even if it is otherwise forgotten, the Crimean was the first war to have been recorded by the camera. Roger Fenton, who travelled to the war zone in 1855, was really the first war photographer and his remarkable pictures are the principal subject of Shadows of War at the Queens’ Gallery.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert took a great interest in the war, not simply as flag wavers, but actively in its human dimension. The Queen established the Victoria Cross as an award for exceptional courage for the first time by soldiers of any rank. Because of this interest, the Royal Collection now holds a comprehensive collection of Fenton’s war photographs. Though he enjoyed their patronage, however, his was not a Royal nor even a government commission – it was a commercial enterprise undertaken on behalf of print-publisher, Thomas Agnew. It was also a huge success. By one contemporary estimate, Fenton’s pictures were seen by two million people. This popular interest was fuelled by reports of the inefficiencies, wasted lives and unnecessary suffering of the war (British casualties were relatively light, but eight times as many died of disease) sent home by WH Russell, the Times’s pioneering war correspondent and subject of a superb portrait by Fenton. It was Russell’s report of the disastrous (and misguided – they were attacking the wrong guns) charge of the Light Brigade that inspired Tennyson’s famous poem: “‘Forward, the Light Brigade!/ Charge for the guns!’ he said. / Into the valley of Death/ Rode the six hundred.”

Agnew saw the commercial potential of photography reporting the war, but hedging his bets his commission to Fenton was primarily to produce photographs for a major painting he had commissioned from Thomas Jones Barker. (The big profits were from prints after the painting.) Scottish artist William Simpson was out in the Crimea, too, producing prints and paintings for the same market. His work is also represented and the exchange between painting and photography is set out in detail in the show.

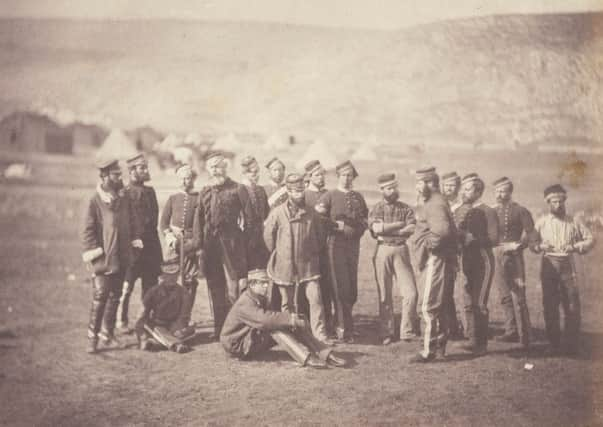

At this stage photography was still no more fleet of foot than painting. One of the best known of Fenton’s photos is his self-portrait riding in the driver’s seat of his cumbrous photographic van. Long exposures meant no action shots. So Fenton took portraits of the allied generals and leading officers, but also of more informal groups of officers and men and indeed women too. The WRACS were not established, but women, even dressed in adapted uniforms, already played a vital support role.

The Light Dragoons, the light brigade of the infamous charge, were of great public interest and indeed he also photographed “the valley of death” where it took place, still scattered with cannon balls. He took two pictures. There are more cannon balls in the second one and he did come under fire. Even so it is not clear whether or not he risked his life to embellish the scene by adding extra cannon balls.

A photographic panorama of the army encampment with the besieged city of Sebastopol in the hazy distance was a major enterprise for Fenton. It’s a great pity it could not fully be reconstructed in the show, the more to be regretted as a huge painted panorama of the Russian defence of the city is the principal attraction of modern Sebastopol.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of Fenton’s most telling pictures are of chaotic scenes in the port and British base of Balaklava. Ships line the wharves three deep. Stores are piled up in the open. Cannon balls lie in heaps like melons in a market. A railway to the front is untidily under construction. Anticipating the First World War, this and the sinister heaps of munitions indicate how the Crimea War saw the beginning of industrial warfare. Here the subtlety of Fenton’s pictures is apparent. In his posed groups of soldiers the harshness of their experience shows through. Even generals were not immune. General Estcourt lies slumped in a chair, eyes closed, exhausted beyond caring. In Fenton’s portrait of one Scottish officer, Lord Balgonie, the subject is standing up, but he looks shattered and barely aware of the photographer or his surroundings. The picture has been identified as the first ever record of shell-shock. Thanks to Fenton’s photography, the archaic myth of the glamour of war is exposed as the cruel fiction it always was.

Shadows of War chimes very well with the exhibition of Josef Koudelka’s fold-out photo books in the Signet Library. Miniature versions are displayed in a glass case, but the main display is of two of the most fiercely polemical laid out in full and 25 metres long. Region of the Black Triangle records the ravaged landscapes of the open-cast coal mines situated in a triangle that straddles the borders of Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. Wall documents the atrocity of the terrible wall that imprisons the Palestinians in the West Bank.

Beside such serious and topical work, Douglas Gordon’s Black Burns in the SNPG is no better than a very expensive one-liner: successful artists do sometimes have more money than sense. Gordon has had made a polished, black marble replica of Flaxman’s white marble statue of Burns and then had it broken up. The pieces lie on the floor and the label informs us that “Gordon liberates Burns from the burden of heroism. Tragedy is brought to the spectacle.” Portentous words cannot enliven the wasteful banality of the image. More interestingly the whole thing is cordoned off and a large notice advises us that “the installation should be viewed from a safe distance.” Health and Safety gone mad, or artistic self-importance?

I would like to be more enthusiastic about the Printmakers show, New Edition, but find it hard. According to the introductory essay by Sarah Lowndes, who has curated this show of barely a dozen rather insubstantial works, it was inspired by the stimulating collaborative atmosphere of the place. Ten posters by a partnership called Poster Club are in keeping with this idea. Each poster is titled The New Erotics. They are repeated, both together and severally, round the room. The best is a reclining fat cat with the legend “corn-fed egotism.” If these are really the erotics of the future, however, it’s a pretty joyless outlook. A set of three quite amiable abstract screenprints by Emer Tumulty is also repeated three times, filling wall space, but not much else unless to make the surely redundant point that prints are multiples. Three screenprints of collages by another partnership, Museums Press, reflect the equipment, but not the sociability of the studio. They too are repeated on table tops and on the walls. Jessica Higgins has written the word “Apologies” twice on the wall with enlarged “Os” for spectacles. It might not be what she intended, but apologies really are in order if this lacklustre show is intended to mark 50 years of inspired printmaking.

Finally, a small exhibition that is pure delight and an island of calm in the general cacophony. Half a dozen artists who all draw, Fiona Robinson, Julia Hutton, Susan Michie, Eric Cruikshank, Steven Maybury and Nigel Bird, have come together in Fault Lines in Patriothall. They do not draw things, however. They just draw, make marks on paper with ink, pencil, charcoal, even with fire, creating patterns of line, of light and of shade, all different, but also all delicate, abstract and serene.

Shadows of War until 26 November; Black Burns until 29 October; New Edition until 21 October; Josef Koudelka and Fault Lines until 27 August, edinburghartfestival.com