Daubigny, Money, Van Gogh and the birth of impressionism

The names of Monet and Van Gogh are guaranteed box office in the art world: witness the queues earlier this year at the Royal Academy in London to see Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse. This summer, the National Galleries of Scotland host a major exhibition which boasts both of these names, but the star of the show is a third artist, one whom many people will barely know.

Charles François Daubigny is not an art world star. There has never been a major international survey show of his work. If he’s known at all, it is as a 19th-century French landscape painter whose sunsets and river scenes hang in the corners of top museums but don’t get much attention. Pointing out Orchard in Blossom, a gorgeous Daubigny from the NGS collection, senior curator of French Art, Frances Fowle, says: “We often have it hanging, but no one ever notices it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

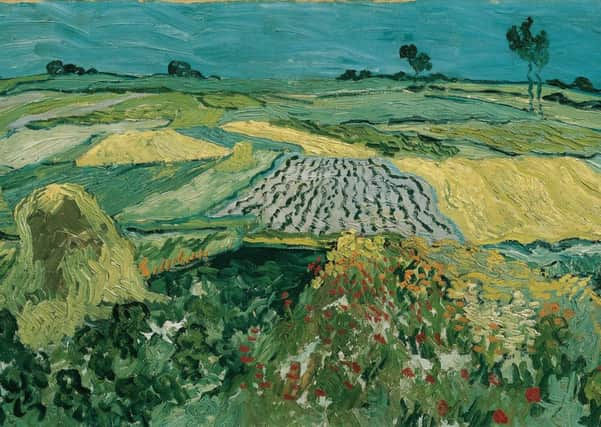

Hide AdInspiring Impressionism: Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh, is an invitation to look again – and be surprised. When one does, landscapes which at first appeared to be painted in dingy greens and browns start to sparkle with unexpected colour. One begins to get the sense of a quiet radical, an artist whom exhibition organisers describe as a forefather of Impressionism who has never been given his due.

“He’s an artist who deserves to be reinstated,” says Fowle. “He deserves to be better recognised. The public don’t really know about him. His whole generation of artists is a big gap in people’s knowledge; they know about Turner and Constable at the beginning of the 19th century, but it’s as if we went straight from them to Impressionism. Actually, there is a whole story to tell which is often overlooked.”

It was Lynne Ambrosini, director of collections and exhibitions and curator of European Art at the Taft Museum in Cincinnati, who came up with the idea of bringing Daubigny back into the spotlight. “Before coming to work at the Taft, I served as a curator at the Minneapolis Institute of Art,” she says. “By chance, the museum owned four paintings by Daubigny that spanned his career from 1843 to 1871. These four pictures were all remarkably different, arrestingly so. They showed a dramatic development from a dark, finicky, Old-Master style to a very broadly brushed, brilliantly coloured later style. His range fascinated me and hinted at a story of transformation.”

The more she looked at Daubigny, the more she realised he was an unsung hero of 19th-century French art. But it has taken nearly 15 years to bring the project to fruition, with the support of NGS and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. It has grown in scope and ambition, not only shedding fresh light on Daubigny himself, but tracing his influence in the work of artists such as Monet, and, more surprisingly, Van Gogh.

Daubigny was born in Paris in 1817, the son of a landscape painter. By the 1850s, when his work was achieving acclaim in the Salon – the pre-eminent artistic establishment of the day – younger artists such as Monet and Pissarro were watching his work with interest. Daubigny’s work was praised, but was also the subject of criticism. In 1861, critic Théophile Gautier attacked him for showing “first impressions” and “neglecting details” in his salon paintings. The freedom of brushstroke and creative use of colour were just the things the up-and-coming Impressionists would have loved.

Daubigny was part of the first generation of artists who painted finished works in oils out of doors, after the invention of the collapsible paint tube. He painted, for a time, alongside members of the Barbizon School in the forests of Fountainbleau, and was friendly with Corot and Courbet, but forged his own path, settling with his family at the village of Auvers-sur-Oise. His work prefigured that of the Impressionists in his choice of subject matter – rivers, cornfields, poppy fields and sunsets – in his compositions, and free handling of paint. By the 1860s, when he was elected to the Salon jury, he championed the cause of artists such as Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Degas and Sisley. He resigned from the jury in 1870 after a painting by Monet was rejected.

Monet clearly looked at his work closely. Part of his first submission to the Salon in 1865 was La Pointe de la Heve at Low Tide, a painting remarkably similar in its composition to Daubigny’s Cliffs at Villerville of the previous year. Monet wrote to Boudin of how he admired Daubigny’s work, and later fitted out his own studio boat in order to paint river compositions from the water – exactly as Daubigny had done nearly two decades before. In 1870, after the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, Daubigny took refuge in London, as did Monet and Pissarro, all three painting scenes on the Thames. It was during this time that Daubigny (who had previously met Monet in Normandy) introduced the two young painters to the French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who would go on to exhibit their work in London, and to support their later careers. When later asked about his relationship with Daubigny, Monet recalled this moment: “He put me in touch with Mr Durand-Ruel, thanks to whom I and several of my friends did not starve to death. It is something I will not forget.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the 1870s, the movement which would become Impressionism was gathering momentum. In 1874, the artists parted company with the Salon, organising their own “Salon des Refuses”. In 1877, Monet’s painting, Impression: Sunrise caused critic Louis Leroy to coin the (originally derogatory) name for the movement. But, if the younger artists were no longer following Daubigny, he was taking inspiration from them. Now in his late fifties and in poor health, he was nevertheless painting with increasing freedom and invention. His last Salon painting, Moonrise at Auvers (1877) handles paint in a way which is almost Impressionist in its freedom.

“There is more free handling, lighter tonality, a brighter palette,” says Frances Fowle. “He started to paint smaller-scale works, and in series (returning to the same spot to paint the landscape in different kinds of light and weather), which some art historians think anticipates what Monet did later. He never developed the Impressionist touch as such but he is responding to them, it’s a two-way dialogue.”

Artists continued to admire Daubigny’s work throughout the 19th century. In 1890, Vincent Van Gogh arrived in Auvers-sur-Oise, battling his own ill health and drawn to the countryside and the legacy of Daubigny, who had died 12 years before. He visited the artist’s widow, and painted her in Daubigny’s garden, days before he took his own life.

“I think he was drawn to Daubigny’s very honest vision of nature,” says Fowle. “He believed passionately in this idea of almost unadulterated vision. There’s a whole series of works that he does in the last few weeks of his life adopting a double-square format, which was a Daubigny format, it enables you to see more of the landscape almost a panoramic view. It’s interesting that, although his style is so radical and very different, he is consciously adopting that. He lists Daubigny in the canon of 19th-century artists who were essentially forging a path towards modernism.”

In art historical terms, Daubigny’s reputation was eclipsed by the younger painters he had supported. Lynne Ambrosini says: “He shared the same fate that befell many earlier 19th-century artists. After the art-loving public became used to the brilliant colours of the Impressionists, all earlier art looked dark and brown. The art market reflects a huge decline in the values attained for their works in the early 20th-century, when Europe and America embraced the Impressionist aesthetic.”

Also, Daubigny’s more radical works have tended to be overlooked, in favour of a series of smaller, darker paintings he made in the last decade of his life for the commercial market. Ambrosini says: “He very likely did this to put aside a nest egg for his family, his health was poor and he knew that his very best pictures often did not sell — they were too advanced in their taste and appeared unfinished and raw to most of his contemporaries. But these weaker pictures have really hurt his posthumous reputation.” By ressurecting his greatest works – including radical paintings which remained unsold in his studio after his death – this exhibition will shed fresh light on an overlooked master.

• Inspiring Impressionism: Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh, is at the Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, today until 2 October, www.nationalgalleries.org