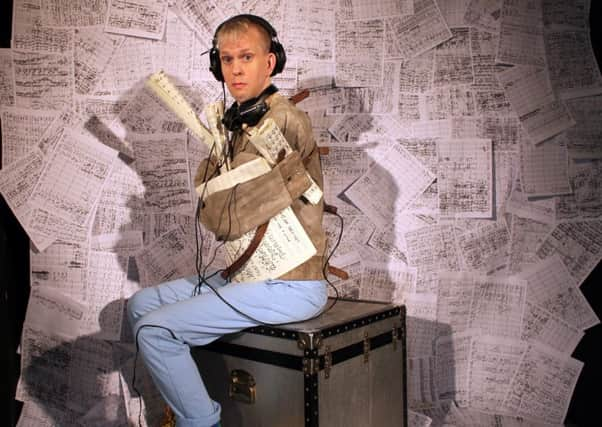

Comedian Robert White on going InstruMENTAL in Edinburgh

“Can die” reminds him that it’s OK if a show goes badly. But also, conversely, not to let the show go badly. “No mental” means “don’t go mental, don’t get caught by the demons in your head”. There’s also “Keep on, just do”. And a clock equalling a pound sign, telling him to complete his allotted time in order to get paid.

Additional notes, on specific fingers, instruct him not to swear or concern himself with groans for his puns, to smile, to be nice, not to be rude, to be humble and “character”, which abbreviates “remember you’re not you, you’re a characterisation of you”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere’s a second entry of “Keep on, just do”. And on the back of his hand he has “Messy rapport”, reminding him to ignore all the other rules if need be. “Don’t be so stringently tied up in everything that you can’t be fluid… if you build a rapport with the audience, you’ve got places to go and a place to go back to”.

This carefully applied ink is crucial help for White, who has Asperger’s syndrome, in maintaining his calm at the start of a show. “It’s to make up for me not having innate social skills” he explains.

On stage, he’s a jack in the box of nervous tics, left-field humour and fizzing creativity. But despite a difficult, lonely childhood and countless sackings from jobs, he was only diagnosed with Asperger’s in 2001 after spending three months in prison. He’s briefly referenced the inexplicable events that led to his incarceration before. But now the musical comic has turned them into InstruMENTAL, a fully orchestrated, mini electro-classical opera in which he plays the piano and other instruments over pre-recorded backing tracks.

Having suffered “a bit of a mental breakdown … with no help, no assistance at all … just the most mental you could ever be” after the end of a relationship, for reasons he can’t explain, he resolved to put on a bizarre costume and visit his ex at work with the express intention of playing a practical joke. Unfortunately, this did not go to plan and the police sought to charge him with armed robbery. After a plea bargain, this became attempting to threaten with an imitation firearm. He was sent to Wandsworth Prison, the UK’s largest, frequently cited as the worst for its treatment of inmates.

Maintaining his innocence, White suggests that young police officers, eager “to get as many brownie points as possible” couldn’t differentiate between “a deliberate act rather than someone who was acting”, failing in their duty to identify him as a “vulnerable” person, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Further, they were “slightly homophobic” he alleges.

A second storyline in InstruMENTAL picks up on White’s struggles with his sexuality and the female “beard” who was once his girlfriend. “I didn’t want to be gay, she asked me out and I said yes because it was a way of not being gay,” he recalls. “She was quite attractive and I was a highly odd, overweight person who thought ‘Why would anyone want to go out with me?’” Although she humiliated, physically and mentally abused him, he stayed with her for a while so he could avoid accepting his sexuality.

These dreadful experiences, coupled with his dyslexia, bouts of depression and an eating disorder, plus the sometime estrangement of his family, meant that “the hell of prison wasn’t as apparent as you might imagine”. Notwithstanding the terrible food, being confined over Christmas and the “evil” sadism of some of the guards, “my life was so broken down that prison wasn’t the worst of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once I’d been there a while, a lot of my mental issues subsided,” he adds. “The older I’ve gotten and the more things have come on top of each other, the more others were normalised. A lot of my very, very autistic traits and bulimia became habitual and everyday because other things were catastrophically worse.”

Music helped. “Once my mum sent in a Walkman and music tapes, it became a bit like college or university because I was writing music too,” he recalls. “Prison is vicious for social, active people. But at school I isolated myself so I’ve gotten good at living in my own head.”

One of his prison compositions now features in InstruMENTAL as an unstated theme. And while the first songs White wrote as a child explored death and empathised with the Elephant Man, he reckons that music has “been a cure for a lot of my depression and self-worthlessness”.

A creative outlet and a calming, repetitive action, performing music also socialised him. “Importantly, when I got older and started to play trumpet in bands, and also the choir when I was very young, it was the only way I actually connected with other people” he says.

Comedy, similarly, has challenged him, forcing him into pubs and clubs, making him interact, though the relationship between his thoughts and artform are far from straightforward. An upside of autism is that his tendency to take words literally, so problematic for his education and previous employment, prompts accidental wordplay that he can then deliberately repeat on stage. The reluctance to read brought about by his dyslexia also taught him to play music by ear, in turn inspiring his impressive gift for improvisation. “Because I don’t think lineally but in blocks, I can put things together that otherwise I might not be able to” he reflects. “I’ve never not had Asperger’s or been dyslexic though, so I can only assume this.”

Naturally, he hates audiences feeling pity for him. In his club set, he doesn’t reveal he has Asperger’s until “my third proper joke. But if, like any comedian, I’m having a tough gig and they haven’t laughed, at the point I mention I have it, I actually feel a bit dirty.

“Instead of a funny person mentioning something about themselves, I’m just someone whose first two jokes haven’t worked adding: ‘Look at me! I’m mental!’”