Cold War spy maps that portrayed a Soviet Scotland

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

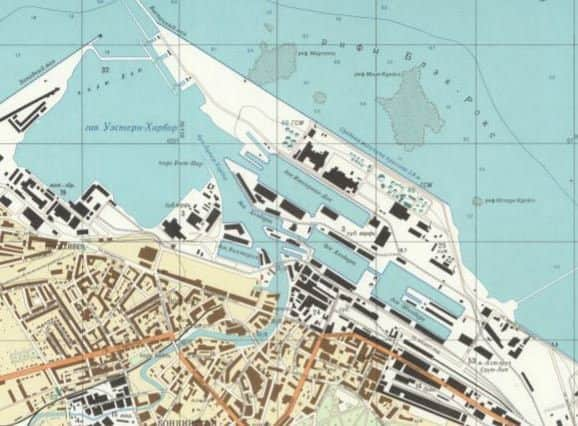

From the end of World War Two till the fall of the Berlin Wall, Cold War cartographers utilised data from a variety of sources to complete the maps, many of which were significantly more detailed than Western equivalents of Soviet-occupied lands.

Secret agents scoured the British mainland for ordnance survey maps, tourist guides, and whatever else they could get their hands on, and married them together with their own Zenit satellite images to produce the scarily-precise plans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe maps covered the globe but the eyes of Stalin, Kruschev and Brezhnev were focused on Scotland as much as anywhere else.

Highly-detailed Soviet-era maps of a large number of our major towns and cities have been discovered since the collapse of communism.

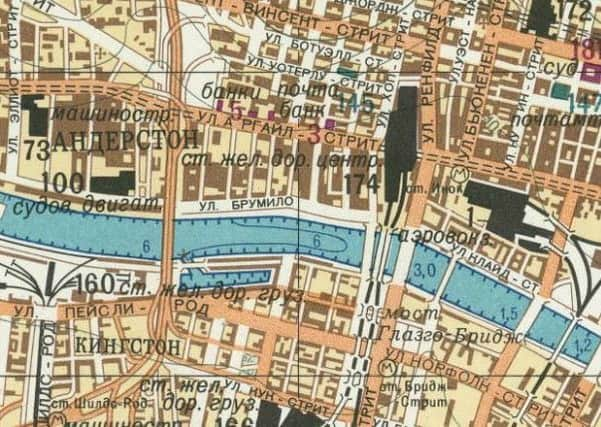

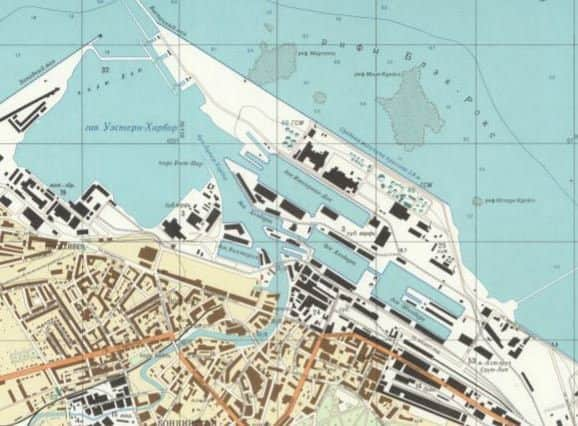

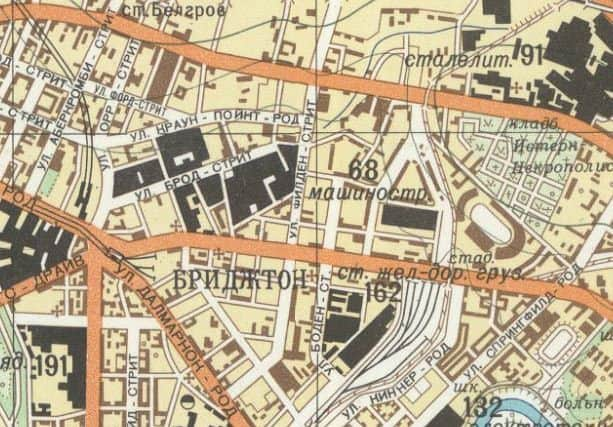

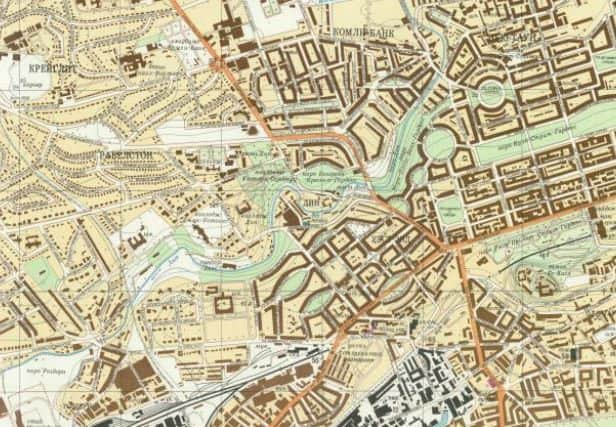

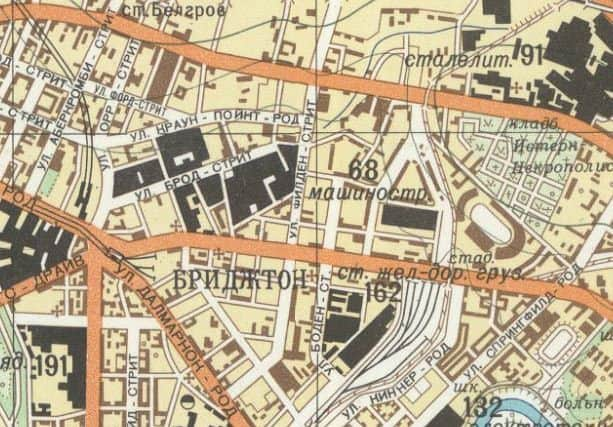

Street names were printed in Cyrillic lettering - chilling in its unfamiliarity - while individual buildings were colour-coded so the Soviets could easily differentiate between industrial zones, government and administrative sites and military targets.

The shipyards and industrial heartlands of Glasgow stand out in stark black along with the city’s many railway lines and terminals.

And in Edinburgh Waverley Station, Sean Connery’s factory-filled Fountainbridge and the docks at Leith are similarly identified as areas of particular note.

Created by a hostile superpower during the most tense years of the post-atomic age, the level of detail alone is enough to make you shudder.

Two men who know these maps better than most are John Davis and Alexander J Kent. The pair have released a book, The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World, the result of 15 long years studying the remarkable maps.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The maps are an incredible combination of British OS data, street guides, plus aerial surveillance and satellite data,” says co-author John Davies.

“The sheer extent of the Soviet mapping project is astounding. Their secret project covered the UK and the world on a large scale.

“Knowledge is power. You collect this information because one day it might be useful.”

John first encountered the maps while working in Latvia as an information systems consultant.

The collapse of the Soviet Union had been so sudden that many of the maps had become publicly available before they could be destroyed.

John picked up his first Soviet map from a local shop at a cheap price and quickly became fascinated by them.

Further examination has lead John to believe the maps were not created with an aggressive invasion in mind, but to prepare for the organic spread of communism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“What is most interesting is the paper quality and print quality is really high,” says John, “These are beautiful maps to look at, real works of art.

“They are huge - almost definitely not for use in the field, but for office use - to control and command.”

First commissioned when Stalin was in power, the maps would have been helpful to control a Britain conquered by communism.

But studying the maps of Edinburgh and Glasgow, it soon becomes clear the maps lacked chronologically accuracy.

One example shows a defunct railway line existing at the same time as the housing development that superseded it, as John Davies explains:

“In Neilston there’s a railway line that was electrified in the 1960s but was abandoned towards Ayr. A residential development was added much later.

“Their Glasgow map shows the railway beyond Neilston electrified alongside the new houses - these never existed simultaneously.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrinted in 1983, but compiled around eight years earlier, the Glasgow & Paisley map displays a number of discrepancies.

The Erskine Bridge, completed in 1971, appears alongside the ferry which it replaced.

Also present is St Enoch Railway Station - closed in 1966 and demolished a decade later - and the Victorian tenements of the Gorbals, which were long gone by the time the map was published.

The seventies was an era of great social change in Scotland’s largest city and the Soviet map makers clearly struggled to keep up with the pace of it.

“This illustrates that they were collecting a lot of data in an asynchronous fashion,” adds John, “Some details in the maps may be the result of assembling disparate pieces of data of different ages and provenance.”

In addition to Edinburgh and Glasgow, the Soviet regime also created detailed 1:10,000 and 1:25,000 plans of Aberdeen and Dundee.

Intriguingly, however, Dunfermline, Gourock and Kilmarnock were the only smaller towns to be featured at this scale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This might just happen to be what we’ve managed to get our hands on,” suggests John.

“Dunfermline is interesting because it doesn’t focus on nearby Rosyth naval base, and the map of Kilmarnock is way earlier than the rest - around 1950-something.

“It might be that there were 1950 versions of all of them and they released revisions in the decades that followed.”

The rest of Scotland’s small towns are indeed conspicuous by their absence, which begs the question: just how many more of these secret Soviet spy maps could still be out there?

• ‘The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World’ is available now on Amazon.