Brickwork: New book charts rise and fall of The Arches, the venue which helped put Glasgow on the cultural map

The Arches was a cornerstone of Scottish culture and a trailblazing venue for theatre, live music and nightclubbing.

But its hard-won reputation seemed to count for little when it lost its late-night licence following a drug-related tragedy, plunging the much-loved venue into administration and triggering the swift demise of a cherished artistic institution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSix years on, a new book sets out to tell the full story of The Arches and the people who made it, on and off-stage.

Brickwork: A Biography of The Arches has been co-authored by Kirstin Innes and David Bratchpiece, who both worked for years at the venue.

It charts the evolution of a venue which helped launch the careers of theatre-makers and performers like Rob Drummond, Kieran Hurley, Richard Madden, Gary McNair, Nic Green, Cora Bissett, Colin McCredie and Richard Gadd.

The Arches would also stage early shows by Massive Attack and Mogwai and play host to Underworld, Daft Punk, 2ManyDJs, Jeff Mills, Felix da Housecat and Carl Cox at its club nights.

The book recalls how the derelict railway arches beneath Central Station were opened to the public for Glasgow’s Glasgow, the most high-profile and much-criticised exhibition in the 1990 programme.

Andy Arnold, the first artistic director of The Arches, was asked by Glasgow 1990 director Bob Palmer to put on street theatre shows in its cavernous spaces and created a venue within the venue, which was dubbed The Arches Theatre.

Arnold recalls: “Glasgow’s Glasgow really was very controversial, especially because it was getting all this money compared to the People’s Palace, which was getting nothing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You also had to pay to get in and there was no exhibition in Glasgow that ever had paid entrance.

“They (the theatre shows) were hugely popular because the whole exhibition was so mechanical and alienating in some ways. And here was something human, you know. And so people gathered round… they loved it.

“The exhibition was incredibly controversial. But because we had our own little theatre thing, we were regarded separately, so we weren’t under the same criticism as the rest of the thing.”

Arnold had to plead with Palmer to leave the 100-capacity seating bank intact at the end of 1990, when he realised the rest of the building was being “stripped out".

“I said: ‘You won’t get any money for it, but there’s no other small scale theatre in the middle of Glasgow. There’s nowhere else, and it would be a great space for theatre companies to come and perform in the middle of Glasgow. Give me a chance to see what I can do with it.’”

Arnold persuaded the then British Rail to allow him to reopen the space for the city’s annual Mayfest event, with salvaged lights, furniture and equipment.

The venue immediately won a “Spirit of Mayfest” award and the city council accidentally awarded the building a 12-month licence, rather than the three weeks of the event. A £10,000 council grant was secured to help keep the venue going.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecalling the early days, its first general manager Lori Frater, says: “At the heart of it all, every single one of us was working 17 or 18 hours a day to keep this place afloat. The only thing that got me through was that I had a business degree. So I knew what had to be done theoretically… I did not know how to do it practically.”

"I don’t think I had a day off in two years. There were times when we weren’t taking any pay because there just wasn’t the money for us to take any wages.

"If it hadn’t been for all of these people literally doing it for the absolute love and belief of doing it, it just wouldn’t have been there. We all learned as we went along.”

Actor Colin McCredie says: “You got no wage as such. Just sixty quid cash in your hand every week. You went because you loved the work. It was Andy Arnold’s troupe of different people. But it was a very grubby place. There were no showers. It had a real guerrilla feel which made it very special.”

The Arches was propelled into the limelight when two fans of the Alien movies secured the rights and permission to run a “total reality experience,” which attracted more than 100,000 attendees.

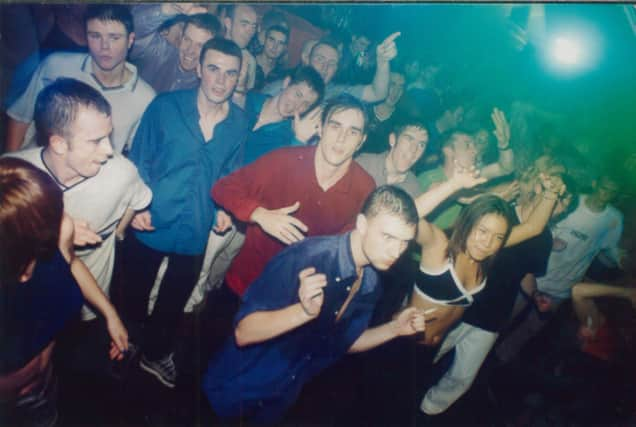

Around the same time in, early 1990s club nights involved Angus Farquhar, founder of the Beltane Fire Festival, house and techno trailblazers Slam and Regular Music founder Pete Irvine, who instigated Café Loco, a late-night event with theatre performers.

Andy Arnold say of Cafe Loco: “We ran it ourselves, and it was massively successful. It was hugely popular. It was a mixture of young clubbers coming and this very trendy set – theatre people, film people like Robert Carlyle, famous musicians. And there were mad things going on all night.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSlam co-founder Stuart McMillan recalls: “I think The Arches just had a warmth and people instantly enjoyed being in that space. It had a big club, big room atmosphere, but with a small room connection. You could see people’s eyes, you could see people’s faces. The connection between you and the public was fantastic.”

Actor and theatre-maker Richard Gadd says: “It felt like a place of pure acceptance, that didn’t cater to the pomp and ceremony of the predominantly white middle-class audiences like most theatres do. It cared about taking chances and making challenging work that pushed the boundaries (and buttons) of normal theatre-going audiences.”

The Arches would draw hugely diverse audiences, often on the same night, as staff juggled bookings for plays, music gigs, corporate functions and club nights, with the venue becoming increasingly reliant on the latter to underwrite the rest of its operations, a financial strategy that was to prove its undoing.

David Bratchpiece, who was latterly front of house manager, recalls: "By the 2010s, things were getting harder in the club as a manager.

“Drugs were changing, things were getting a lot more unsafe. Younger people were coming in – and we were really strict on the door – but it’s no secret that The Arches was the club people came to get mad with it.

"Increasingly we were seeing some horrific things in the first aid room. For the whole history of the club, people have always taken pills, but they’d always been a bit more able to look after themselves. The states that we were seeing people getting into was something new.”

Lisa Dunigan, joint head of security, says: “It wasn’t The Arches that changed, it was the people that came and what they expected, and how they thought they could act. And the culture.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn February 2014 an under-age clubber, Regane MacColl, from Clydebank, collapsed inside The Arches and later died in hospital. Her death was linked to an ecstasy-like tablet, "Mortal Kombat.”

Regular concerns were raised by the police over the venue, which eventually lost its late licence in May 2015 after a warning there would be “potentially lethal and profound consequences” if action was not taken.Weeks later, the venue, which had received more than £11.2 million in public funding since it opened its doors, went into administration, more than £420,000 in debt and with the lost of 129 jobs.

Mark Anderson, executive director in The Arches’ final years, says: “We did our best, we won a lot of awards, we did everything we could. But when you are up against the dark forces of Police Scotland, and the tyrant chief constable we had at the time… he had it in for us.

"We were held up as a beacon of self-sustainability by the Scottish Arts Council and then Creative Scotland.

"What I don’t think I’ll ever forgive Creative Scotland for is that they abandoned us. In our hour of need. And Glasgow City Council. You know, collectively, they bottled it.

“If they had plugged the gap, then The Arches would still be going today.”

Andy Arnold said: “There was no real desire to do anything. You’re talking about peanuts relatively, for a major Scottish arts venue, a few hundred grand just to keep it going while things were sorted out. And instead, they wound up, administrators with unseemly haste sold everything, and that was the end of that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe building occupied by The Arches later reopened to the public under new management as Platform, a bar, restaurant and events complex, while a neighbouring site is now home to a Motel One hotel.

Jackie Wylie was the last artistic director of The Arches. She says: “I think the thing that is really impossible to reconcile is the building, and the loss of a physical, subcultural space.

“There’s that hotel that exists on the front of the building now, which feels like an absolute affront to me… in some ways it’s like progress, or those things that we feel we can’t be in control of… there’s a feeling of powerlessness against that kind of gentrification. But there’s something about the whole thing that’s so troubling.”

Brickwork: A Biography of The Arches, by Kirstin Innes and David Bratchpiece, is published on 4 November.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.