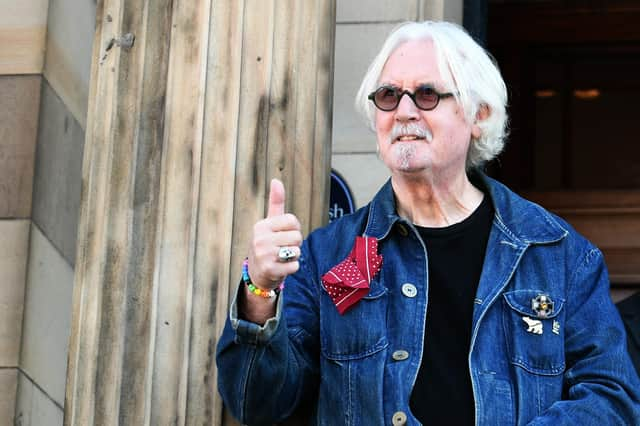

Billy Connolly's Windswept & Interesting book review: Big Yin has grim tales but this is no misery memoir

But Billy Connolly, who trumps the rest at humour to claim the title of the world’s greatest stand-up, has just trumped them at grimness as well.

In his memoir Windswept & Interesting, the Big Yin relates tales of unimaginable cruelty. Actually, the casual sadism of 1940s and 1950s Scottish schoolteachers isn’t so much of a shock because as you read you can hear Connolly in his stage shows impersonating these chalkdust-flecked monsters, making them seem funny.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The nuns were very violent,” he writes. “Their punishment tool was a 12ins ruler they’d crash down on our knuckles, even in infants’ school.” A teacher nicknamed “Big Rosie” placed pencils under hands to cause extra pain - “a psychopath”. In music lessons - step we gaily, on we go - noses would be smashed into desks: “Come on, Connolly! SING IT!”

But it’s what happens to him at home in Glasgow which takes your breath away. It cannot be mined for laughs so you’re not hearing his raucous voice. There’s Auntie Mona: “She’d smack me in the face so my nose bled. She whacked me with wet towels, kicked me, battered my head with her high-heeled shoes. But her speciality was humiliation - grabbing me and rubbing my dirty underwear in my face.” Once, rather than return home after school, he trudged 12 miles the other way - to Hamilton. “I thought a lot about drowning myself in the Clyde.”

And it gets worse. We know all about Connolly’s comic timing from his long psychedelic rambles but how about this sentence for tragic timing: “My father sexually abused me for years.” It comes just as his dad, William, learns about Mona’s tyranny and you think he’s going to put a stop to it. “A horrible, secretive routine,” Connolly says of the ultimate betrayal from the age of ten to 14. “And for the following 20 years - until my father died - I just buried all that shame.”

But we cannot position Windswept & Interesting in the Misery Memoirs section, not with the Big Yin involved. There’s a lot of love in the book, not least for his sister Florence. While William was fighting in Burma, their mother, Mary, would leave the children alone in the house with the fire open and blazing, Florence once falling into burning ashes and permanently damaging an eye. But, just 18 months his senior, it was she who looked after Connolly. “Florence bathed me, fed me, dressed me.” When he was only four his mum ran off with another man. “I don’t remember her hugging me,” he writes.

Young Billy, possessed of “a face that would get you a scone at every door”, was forced to wear wool swimming trunks. Unable to afford Brylcreem, he’d sneakily suck cream from the nozzle. He chuckles at such privations so we can, too. He made friendships in the playground which endured for 70 years and can remember when his dad was a dad, buying him flippers, encouraging him to take up the banjo, turning him onto PG Wodehouse.

But Connolly discovered Charles Dickens by himself aged 12 and learned French from tapes. “Everything I achieved in life came from Partick Library.” And the key thing: that he could make his own way in the world.

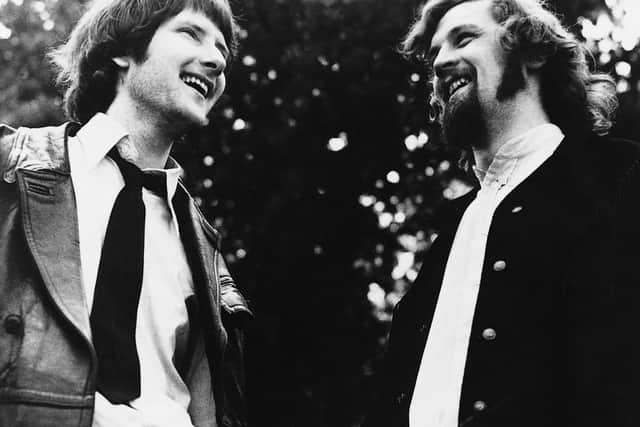

Not entirely unaided, though, for he acknowledges the camaraderie of camping mates and biker gangs where he discovered three things: he could make others laugh, be funny without jokes and the west of Scotland cultural experience was valid subject matter. And the Parachute Regiment and working as a welder in the shipyards - after school, the church and family had all failed him - made him feel “like I belonged in the world, that I was no longer prey … I felt like a successful human, a man”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are laughs in the book as Connolly riffs on various likes (biscuits, getting his bum out, fishing, babies, snow globes, cowboy boots, Chic Murray, the hairy-nosed wombat) and dislikes (musicals, wholemeal bread, religious piety, board games). But he soon returns to the dark side to ’fess up to his street-fighting years on the folk scene and keeping the paparazzi at bay (“A healthy smack in the mouth does a power of good”), his battle with the bevvy and how a drunken prank on a bus almost killed Michael Caine and the break-up of his first marriage.

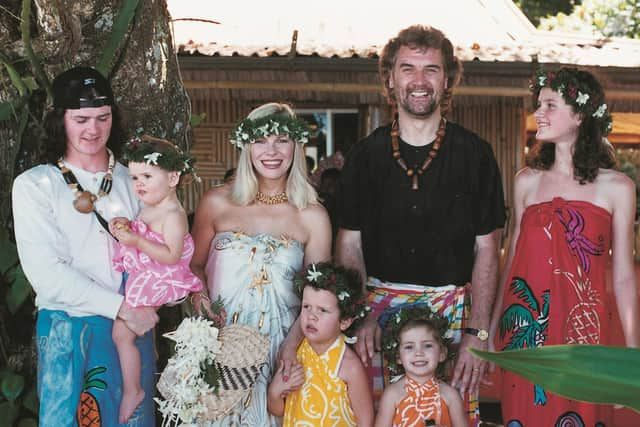

His mother’s desertion and Auntie Mona’s habit of producing his soiled pants when girls called round for him - he likens her to Bette Davis’ character in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, only with the teeth kept in a glass - caused him to be scared of most things, not least the opposite sex. It all worked out fine, though, when Pamela Stephenson took him in hand. “I’m a lucky bugger,” he remarks more than once.

The Parkinson’s disease he contracted in 2013 restricts his banjo-playing but not his shouting at the TV. Now based in Florida, he doesn’t like the sand - a legacy perhaps of knitted swimmies days - but in every other respect a place created by “pirates, vagabonds, scoundrels and nutters” and populated by “some brilliant human crazies” is very much to his liking.

Though he misses Scotland and football he says: “I’ve got no complaints. “I’ve got shelter, food, my wifey and my girlies and my son and my grandchildren.” He’s been determined to give his kids the love and support he didn’t get. They don’t like his movies where he doesn’t make it to the closing credits and there have been a few of them. He writes: “I feel happy just as I’m about to go to sleep … I’ve always imagined that would be the feeling you get before you die.”

Windswept & Interesting (Two Roads, £25) is published today.

A message from the Editor:

Get a year of unlimited access to all of The Scotsman's coverage without the need for a full subscription. Expert analysis of the biggest games, exclusive interviews, live blogs, transfer news and 70 per cent fewer ads on Scotsman.com - all for less than £1 a week. Subscribe to us today

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.