Biggest ever exhibition examining crimes of Burke and Hare set to open in Edinburgh

It is also inextricably linked to the evolution of Edinburgh as a global centre for the study of medical research.

Now the biggest ever exhibition exploring the crimes of William Burke and William Hare is to take centre stage in the city – nearly two centuries after their deaths.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe National Museum of Scotland (NMS) exhibit, which opens on 2 July, will examine what prompted a killing spree that claimed 16 lives in the space of a year, the part played by the city’s medical establishment and the fall-out from a controversial investigation that came to a head on Christmas Day.

The Burke and Hare story is at the heart of the exhibition, Anatomy: A Matter Of Death And Life, which charts more than 500 years of medical exploration around the world.

Exhibits linked to the killers are being brought together for the first time in the museum, which is on the doorstep of the key locations where their story played out.

The roots of their murders can be traced back to the 16th century when the town council played a key role in instigating both Edinburgh University and the forerunner of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Dr Tacye Phillipson, NMS senior curator of modern science, said: “By the early 18th century, Edinburgh had become one of the leading places in the world to study medicine. The council was persuaded to foster medical education so that students did not have to go to Continental universities. The city had a very large medical student population compared to its overall population.

“More and more students were demanding hands-on experience of dissection. It also became more and more competitive for student fees. Lecturers needed a supply of bodies, so this murky industry of digging people up from graveyards and selling them to anatomists developed. Watch towers were built in graveyards and heavy iron mortsafes were put around coffins.

“Everybody in Edinburgh knew that a body was a valuable commodity. By the early 19th century, they were being shipped to the city from London, Liverpool and Ireland.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1828, William Burke was staying in a lodging house in the West Port, near the Grassmarket, close to where William Hare, a fellow Irish navvy, lived.

When a fellow lodger died owing Hare money, they decided to see if they could cash in on his demise.

Dr Phillipson said: “They went wandering over to the university to ask where they could find an anatomist and were directed to Robert Knox, a private anatomy teacher, who had the most students and used the most bodies in the city. He was delighted to see them and gave them seven pounds and 10 shillings. They were then tempted by the thought of making more money.”

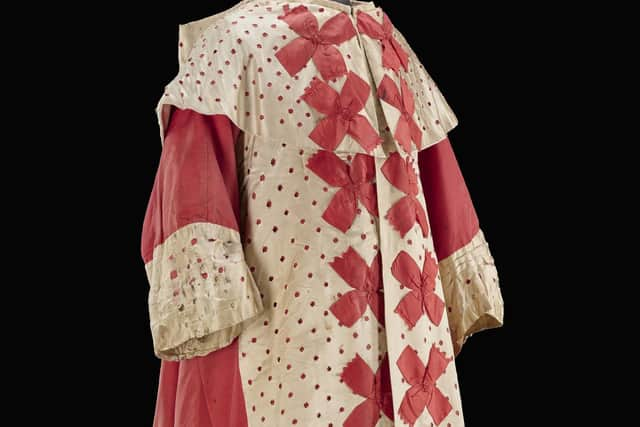

Burke and Hare developed a distinctive modus operandi: their victims were usually lodgers or people they had invited in for a night of drinking. They would wait until the victim was intoxicated before murdering them by sitting on their chests and applying pressure to the lower jaw, a method which became known as “burking”.

Their undoing came on Halloween 1828 when they claimed their 16th victim, Mary Docherty.

A visiting couple, James and Ann Gray, were asked to move out of Burke’s lodging house, but returned the following day to retrieve some belongings – only to find a body underneath a bed.

Despite attempts by Hare’s partner Margaret and Burke’s wife Helen MacDougall to bribe them, the visitors called in the police.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Phillipson said: “The investigation went badly. There was very little actual evidence of murder and selling a body was notably not a crime. There was a lot of suspicion and their stories were inconsistent, but not enough proof to secure a conviction.

“There was also huge anxiety about the whether this was going on all over the country, and whether every anatomist was using murder victims.

“The only way the Lord Advocate [Sir William Rae] could see through it was to get one or more of the suspects the opportunity to confess in return for immunity from prosecution. The two women refused to talk. It was felt Burke was probably the leader, so Hare was offered the opportunity.”

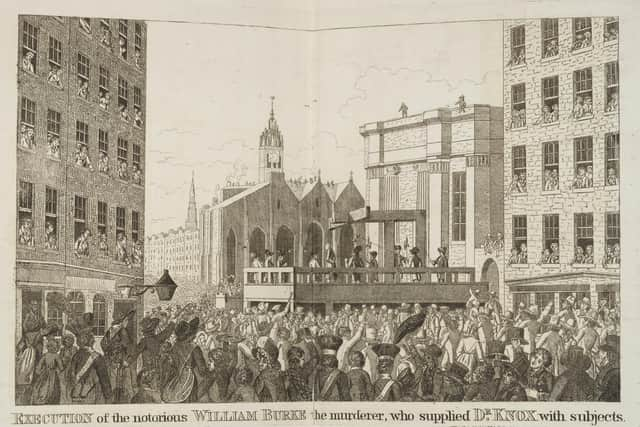

Burke was convicted on Christmas Day 1828 following a trial the previous day, and executed the following month.

Dr Phillipson said: “More than 20,000 people watched Burke be hanged in the Lawnmarket.

“His body was publicly dissected in a university anatomy room. But there was quite a lot of unrest as all the spaces were taken up by the great and the good of Edinburgh and there wasn’t space for the anatomy students.

“When it was opened to the public, an estimated 20,000 people walked past to see his corpse. There was huge interest in trying to work out what makes a murderer. It’s an enduring fascination.”

The exhibition touches on two long-standing mysteries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHare was forced to flee Edinburgh due to public outrage that he had evaded justice. He left in disguise for Dumfries, but was recognised by a fellow coach passenger and the police helped him escape a mob on his arrival. The last confirmed sighting on him was on the road to Carlisle. He was never heard of again.

Seven years later, a group of schoolboys hunting for rabbits on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh discovered 17 miniature coffins hidden inside a small cave.

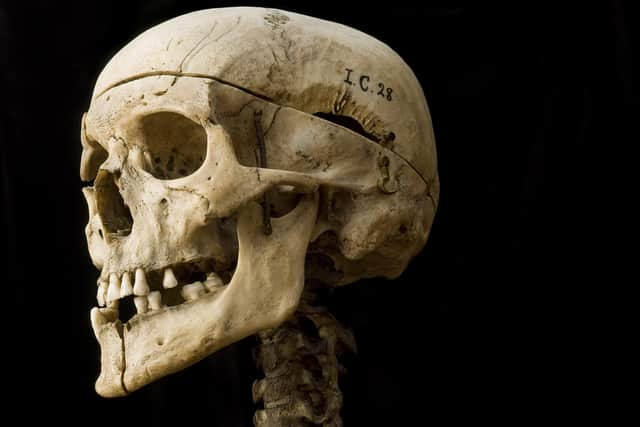

Some of these coffins – described by the museum as “a mystery that will probably never be unravelled” – will go on display this week, alongside other objects linked to the serial killers, including portraits, Burke’s skeleton and handwritten confession, accounts of the court trial and an illustration of the execution scene.

Dr Knox escaped prosecution and was even one of the 55 witnesses at the trial, although he was never called to the stand. His reputation was tarnished however, and he left his Edinburgh home at 14 Newington Street, in an attempt to shake off the cloud over his reputation, settling at the Cancer Hospital in London. He died in 1862.

The crimes of Burke and Hare and the outcry they provoked were to pave the way for the Anatomy Act, passed in 1832, which ensured that unclaimed bodies, including those who died in prison or hospital, or those that were donated by relatives, could be used for the study of anatomy and medicine.

Dr Phillipson added: “The story of Burke and Hare is one of the most powerful and well known associated with Edinburgh. The exhibition takes a very clear-eye look at them without being sensational and very much sticks to what the evidence tells us and what the situation was in Edinburgh at the time.”

Other displays will feature a medicine cabinet used at the Battle of Culloden, a heavy iron “mort safe” placed over a coffin to deter body-snatchers, and a full-body anatomical model by pioneering French model-maker and anatomist Louis Auzoux.