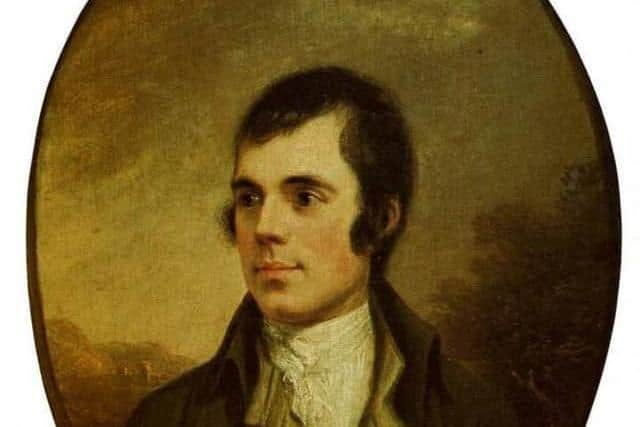

Auld Lang Syne: The truth about the famous Scottish poem by Robert Burns

‘…I may say, of myself and Copperfield, in words we have sung together before now, that

“We twa hae run about the braes

And pu’d the gowans fine”

— in a figurative point of view — on several occasions. I am not exactly aware,” said Mr. Micawber, with the old roll in his voice, and the old indescribable air of saying something genteel, “what gowans may be, but I have no doubt that Copperfield and myself would have frequently taken a pull at them, if it had been feasible.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the years since it was written, many millions must have sung ‘Auld Lang Syne’ while sharing Mr Micawber’s ignorance of what many of its words actually mean (gowans are daisies; the song’s title might be translated as ‘days long past’).

And many of us who can’t really sing go through most of the year without singing a single song by Robert Burns, and then, within the space of 25 days, sing this one twice.

‘Auld Lang Syne’ has become a fixture of the first minutes of 1st January; it also ends any celebration of Burns’s birthday on the 25th. And it ends many a wedding and ceilidh in the same way: the singers in a circle, holding hands, then crossing arms for the last verse (‘And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere! / And gie’s a hand o’ thine!’), then, if you are on a dancefloor, dancing in and out from the centre of the circle for the chorus, with a degree of vigour varying according to the quantity of youth, enthusiasm, and drink enjoyed by the participants.

It has become a ritual to round off a convivial evening, a prelude to farewells, a promise that we will do this again sometime.

Of course, it is not Burns’s whole song that usually gets sung on these occasions, but only the first and last verses, with the chorus repeated after each (then sometimes again and again until people start falling over).

The verse with the gowans, the middle one of a full complement of five, is rarely aired to perplex contemporary Micawbers; the second is also best omitted, since it is encouragement, not to go home, but to go back to the bar:

And surely ye’ll be your pint stowp!

And surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

And this points to a curious fact about what has become a paradigmatic song of parting, that its full lyric is the opposite of this: it is a song of reunion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScottish heritage: for stories on Scotland’s people, places and past >>

There was, in Burns’s own time, a traditional Scottish song of farewell, but it was not this one.

It was called ‘Goodnight and joy be with you a’’, and Burns instructed James Johnson to use it as the 600th and last song in The Scots Musical Museum, the six volume collection on which they collaborated (‘Auld Lang Syne’ was first published in the fifth volume).

Burns had already set a lyric to this tune called ‘The Farewell’, which had appeared near the end of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect of 1786, the volume that shot him to fame.

This is one of Burns’s explicitly Masonic pieces, addressed to ‘the Brethern of St. James’s Lodge, Tarbolton’, apparently in anticipation of Burns’s emigration to Jamaica and a job as a plantation overseer:

Tho’ I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursuing Fortune’s slidd’ry ba’,

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I’ll mind you still, tho’ far awa.

This lyric is the one used at the end of The Scots Musical Museum, but Burns places alongside it the words that traditionally accompanied the tune.

There are plenty of songs in the Scottish tradition before Burns that are set to a tune called ‘Auld Lang Syne’ but Burns’s song does not seem to be based on any of these (Burns’s songs are frequent adaptations and refinements of traditional material).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe claimed in a letter to his friend Frances Dunlop that it was ‘an old song and tune which has often thrilled thro’ my soul’, and later to the other publisher of his songs, George Thomson, that he ‘took it down from an old man’s singing’.

But as his career progressed Burns become more comfortable in the posture of anonymous mediator of national tradition than in that of the famous national Bard, and the words of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ are almost certainly an original composition by Burns despite his claims to the contrary.

That he was willing to consider different tunes to which these words could be set might confirm this: they first appear in the Museum set to one traditional air, but he was happy to suggest a quite different one to Thomson, and it is the latter tune to which we sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ today.

This does not suggest reverence for a traditional unity of ‘old song and tune’ of the sort certainly demonstrated by ‘Goodnight and joy be wi’ you a’’. And Burns’s most obvious borrowing in ‘Auld Lang Syne’ is not from any identified traditional song but from an original one by Alan Ramsay, ‘The Kind Reception, to the tune of Auld Lang Syne’ which first appears in a slim collection of Scots Songs published in Edinburgh in 1718:

Should auld Acquaintance be forgot,

tho’ they return with Scars,

These are the noble HEROE’s lot,

Obtain’d in Glorious Wars. […]

Ramsay’s song is, like Burns’s, a dramatization of reunion, not parting: it consists of four verses in the voice of a woman welcoming back her lover from foreign battlefields, before a final verse which confirms that they got married the very next day!

Why did ‘Auld Lang Syne’ come to supplant ‘Goodnight and joy be with you a’’ as the traditional Scottish song of parting, then? Perhaps the answer lies less in whether they celebrate departure or return than in the specific sorts of absence that they imagine in between. Ramsay’s returnee is a gentleman mercenary, returning to his bottle and his dogs as well as his lover. And the speaker of ‘Goodnight and joy be with you a’’ seems to be some sort of criminal going into some sort of exile:

The night is my departing night,

The morn’s the day I maun awa:

There’s no a friend or fae o’ mine

But wishes that I were awa.—

What I hae done, for lake o’ wit,

I never, never can reca’:

I trust ye’re a’ my friends as yet,

Gude night and joy be wi’ you a’!

When Walter Scott included a version of this song in The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border under the title ‘Armstrong’s Goodnight’ he ascribed it to one of that notorious border family on the eve of his execution for murder: in the context of The Scots Musical Museum it is more likely to evoke a Jacobite rebel fleeing arrest after Culloden.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut political exile in France, like fighting in foreign service in Flanders, was a game for the gentry. ‘Auld Lang Syne’ imagines the end of a more distant absence: ‘But seas between us braid hae roar’d / Sin auld lang syne.’

And this song was written and published at the beginning of an age of mass emigration from Scotland, of hundreds of thousands of ordinary people crossing the Atlantic, or taking the longer haul to Australia or New Zealand, in pursuit of ‘Fortune’s slidd’ry ba’’, just as Burns himself had once planned to do (and as Mr Micawber does in David Copperfield).

Many of those hundreds of thousands must have taken this song with them, in their luggage or in their memories: a song of parting to be shared with new friends and neighbours, but which imagines a reunion with friends and family in the old country, a reunion which most of its singers were destined to experience in no other way.

Dr Robert Irvine is a lecturer in the University of Edinburgh and editor of Robert Burns, /Selected Poems and Songs/ (Oxford World’s Classics, 2013). This is an update of the original article on account of a publishing system update.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.