Arts review: Gillies & Maxwell | Demarco & Beuys

William Gillies & John Maxwell | Rating: **** | City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys: A Unique Partnership | Rating: ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArtist Rooms Joseph Beuys: A Language of Drawing | Rating: *** | Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Kenny Hunter: Reproductive! | Rating: **** | Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop

William Gillies and John Maxwell were close friends and that friendship is commemorated in the 40-plus works bought from them by Harold and Betty Fletcher over 30 years up to Gillies’s death in 1973. This collection has been on loan to the City Art Centre in Edinburgh for the last 20 years and provides the majority of the works in the exhibition William Gillies & John Maxwell. It is a great pleasure to see it in its entirety again.

Temperamentally the two artists were very different. Gillies was immensely prolific and painted what was in front of him. Maxwell was dreamy, mostly painted from his imagination and was intensely self-critical, often destroying his work. A typical note from Gillies when they were together on a painting trip reports that he has already done six watercolours, but “Johnnie hasn’t started yet.”

Both men studied in Paris. Later Maxwell played a part in bringing a Paul Klee exhibition to Edinburgh in 1934 and Gillies was much inspired by an exhibition of Munch’s landscapes the previous year, but for all this exposure to modernism, they tended to keep their distance from it. Indeed, some of Gillies’s latest work, the lovely painting, Temple, Dusk, in the ECAC’s permanent collection for instance, seems almost timeless. Only the abstract subdivision of the painting by window astragals hints at the freedoms of modernity. Likewise, in a later work, Birds against the Sun, Maxwell plays with the abstract shapes of the birds’ wings, but it is abstraction as a kind of stylisation, a system of design, not as an alternative way of seeing the world.

It might be that Scottish society was still too conservative, or perhaps, cut off from Europe by the war, they later lost confidence. The show is set out chronologically and certainly their most adventurous years were the thirties. A dark painting of Woods at Humbie from 1936 shows Gillies absorbing the lessons of Munch’s expressionism, while a series of remarkable watercolours that he painted on the west coast show him learning from Klee as well. His response is mature and quite his own, however. These are superb modern pictures and are in marked contrast to the rather stodgy essays in cubism that he had painted after his time in Paris. There are three of these beautiful west coast paintings in the Fletcher collection. Big and boldly painted, they are among the finest and most original things that he did. The freedom and transparency of the medium mimics wonderfully the light and weather of the west.

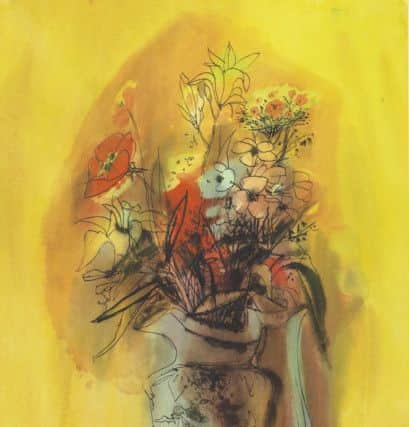

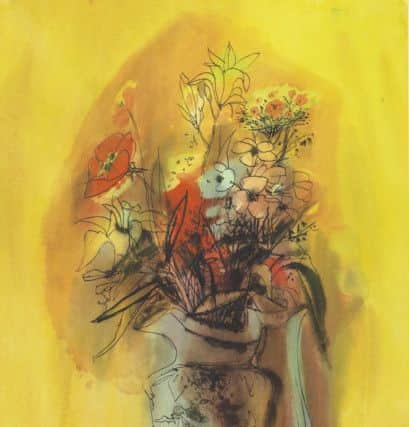

The Apple from 1928 by Maxwell, a mildly sexy etching of Adam and Eve with some naked friends, shows his awareness of Picasso and perhaps also of Chagall. The inspiration of Chagall is apparent too in Still Life in the Country from 1934, a still life of flowers with birds and naked women drifting about in a golden haze. The flowers also suggest Van Gogh, however, as does the handling, but sometimes following this inspiration Maxwell gets bogged down in his paint. Really he is at his best on paper in works like the wonderful Yellow Flower Piece, in Three Figures (Nudes), or in Study for the Trellis, in which he uses fluent ink drawing over washes of watercolour. Female nudes feature in all of these (they’re on the vase in Flower Piece) and Maxwell’s painting is constantly touched by this kind of wistful eroticism. It is where his imagination met that of Chagall. The only women in Gillies’s life, on the other hand, or perhaps even in his imagination, seem to have been his mother and sisters with whom he lived all his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRichard Demarco was a student at Edinburgh College of Art when Gillies was a dominant influence there. Although he did not study painting, his own art shows how much Gillies was an influence on him, but perhaps, too, this was not just in his art. Gillies’s life demonstrated with near monastic dedication his belief in the importance of art as a calling. Demarco’s own career also seems to have been driven by a passionate belief in the power of art and in the role of the artist. The three most important artists with whom he collaborated, Josef Beuys, Ian Hamilton Finlay and Tadeusz Kantor, all in different ways personified this, though in choosing them he departed radically from Gillies’s example. In 1970 Beuys came to Edinburgh for Demarco’s palindromically named exhibition Strategy Get Arts staged in Edinburgh College of Art. Concurrent with a major exhibition of Beuys’s drawings, this groundbreaking show and Demarco’s subsequent relationship with Beuys are the subject of a richly documented exhibition at the SNGMA, Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys: A Unique Partnership. It would be an understatement to say that the reaction of the artistic establishment in which Gillies was a central figure to Strategy Get Arts was unfavourable, but the exhibition of Beuys’s drawings shows why that was not at all surprising. For the likes of Gillies and Maxwell, art’s fulfilment was in the completed object. It was autonomous. Its values inherent, it needed no gloss. For Beuys the opposite was true. His drawings are not autonomous. He gives them any meaning they have. It is therefore extrinsic, not intrinsic and in his lifetime was provided by the performances, actions, lectures and statements on which his drawings often comment. Now their meaning can only be provided by labels which explain for instance how the rather organic looking brown paint he often used “reminded the artist of the walls and floors of houses in his native Germany, and recalls earth and nature or the blood and soil of German nationalism.” Thus the drawings in A Language of Drawing reflect the peculiar symbolism he used in his advocacy of art as an alternative to prevailing values and systems of power. There is little in them to charm or seduce. Indeed they are really not very good at all, but that is not the point. He was more secular saint than artist; these drawings are the relics of a saint.

Beuys’s example was hugely liberating. He reinvigorated the belief that art could and should reach beyond itself to act in the world. Nevertheless, his is a medicine to be taken with caution. Not all our artists can be secular saints and the idea that a work of art has meaning because the artist says it does has proved more a recipe for perplexing labels than good art. The status quo always co-opts the avant-garde to serve its own purposes, not those for which it once fought. Much has been done in his name that is as self-serving as the systems he criticised with such force.

Kenny Hunter has both embraced the wider purpose of art espoused by Beuys and remained loyal to the autonomous object as its vehicle. His show Reproductive! at Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop doesn’t need labels but invites reflection. Its theme is how reproduction changes things. Two versions of a child’s head, for instance, one in plaster the other in polished bronze, demonstrate how profoundly a cast can differ from its matrix. Similarly a group of enormous models of potatoes show what an effect reproduction in different scales can have. Edinburgh’s Folly was to have been a reproduction of the Parthenon, but a photo of it becomes four more quite different reproductions in four screens of colour printing. There is much else, but the ensemble is a fascinating essay in the elusive status of the images with which we are surrounded.

• William Gillies & John Maxwell until 23 October; Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys: A Unique Partnership until 16 October; Artist Rooms Joseph Beuys: A Language of Drawing until 30 October; Kenny Hunter: Reproductive! until 24 September