Art reviews: William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland | Marvin Gaye Chetwynd

William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland: Conversations in Letters and Lines ****

Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd: Uptight upright upside down ***

CCA, Glasgow

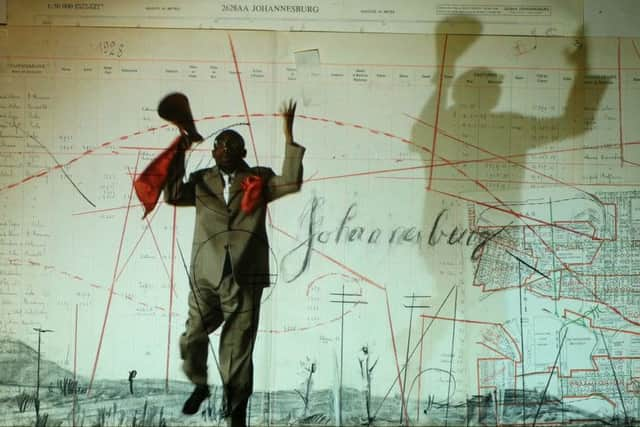

Last week the queues to hear the artist William Kentridge speak in Edinburgh wound all the way down Market Street. The South African artist, at 61, is acknowledged as one of the great artistic figures of the era. In drawings, print-making and opera design, but most of all in the charcoal and ink animations which are his signature works, Kentridge has made the story of his home country with its erasures and evasions, its violence, lies and dissimilation, into the story of our times.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the Fruitmarket he shows with Vivienne Koorland, a long-standing friend and eminent painter whose work is far less well known in this country. Koorland’s paintings are drawn and inscribed, stitched and smeared on linen and burlap. Her world is one of ghosts: paintings map out in bleak and scorched earth colours the land that has been grabbed, farms destroyed and families deported, firstly under colonial conquest, subsequently under apartheid era policies of forced eviction.

Even as South Africa tries to change its future Koorland sees a failure to confront its past. Her painting of watchtowers at America’s high security Angola prison marks their removal to the new museum of African American history in Washington. Scrawled at the bottom of the painting is Nelson Mandela’s name, thus begging the question of how his own imprisonment might now be best remembered.

Kentridge, the son of two Jewish lawyers who represented clients whose lives had been thwarted by apartheid, studied politics before he became an artist. It saturates all his work, but is presented as a deeply personal dilemma through his recurring characters – the heartless capitalist businessman Sol and his opposite, the melancholy and humane Felix.

Kentridge’s art is one of erasure and layering: he draws and rubs out on the same sheets to make his animations. Similarly, his works tells of the deep archaeological layers of injustice as landscapes cover over and obliterate the past, and his characters dance over thick textbooks of mining records.

As a child, Kentridge accidentally discovered a work file of photographs that belonged to his father. They showed the broken bodies and bloody aftermath of the notorious Sharpeville Massacre. It is the moment to which his art has returned all his life, in an act of uncovering and remembering.

It would take more space than is available here to sum up the family story of Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, the British performance artist whose real name is Alalia, who changed her working name to Spartacus in 2006 and thereafter to Marvin Gaye. The names are symbolic of her work’s shape-shifting attitude to art and gender, her playfulness and a certain sense of casual voracity when it comes to adapting other people’s stories for her own creative purposes. Chetwynd’s family inheritance includes both performance and design: her mother is the Oscar-winning production designer Luciana Arrighi, who won her Academy Award for Howard’s End and was a mannequin for Yves St Laurent as well as a scenographer and set designer for Ken Russell.

Part anthropologist, part theatre director, all bohemian, Chetwynd is the leader of a travelling troupe of artists and performers who, for over 15 years now, have led a cheery rebellion against the chilly professionalism of much of the art world, with papier-mache, props, improvised costumes, flashes of flesh and lashings of face paint.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChetwynd channels classical myth and modern paganism in performance. The breath of fresh air has largely been welcome and Chetwynd moves successfully from large scale works with children and communities to the commercial gallery system and museum style exhibitions and events. Nominated for the Turner Prize in 2012, she moved from London to Glasgow a few years ago, refreshing her stock of collaborators as well as injecting the local scene with a bit of her va va voom.

At CCA, Chetwynd has mostly pulled off what has been a tricky proposition for her art practice – how to sustain an ongoing exhibition in the absence of her anarchic and charismatic troupe. The show starts with three instalments of her ongoing episodic films Hermitos Children, part detective story, part creation myth. If none is exactly coherent, then incrementally they do improve. The 2008 episode is homespun to the point of unintelligibility, but as they progress her films begin to communicate more clearly the humour and energy evident in her performances.

Chetwynd’s inspirations range from the naturalist Joy Adamson to the utopian thinker and designer Buckminster Fuller. Although she trained in anthropology before studying fine art she brings an auto-didactic zeal to her subjects. A room at CCA is dedicated to an archive of the fanzines she creates for each event, each one a useful guide to her roving interests.

The show at the CCA, entitled Uptight upright upside down, leans heavily on the literary scholar Bakhtin’s idea of the reversal of hierarchies that is evident in the carnival culture of the medieval period, in the peasants’ revolts and in working class rebellions like the Rebecca Riots in 19th century Wales or Luddism in 19th century England. The focus here is on the Japanese erotic illustrations known as Shunga, where sex is cartoon-like, extreme and infinitely pleasurable. Scattered props refer to mythical beasts and outrageous human anatomy. What feels missing is a clarity of purpose to match the potential that all this cheerfully promises. For in Trump times and in Brexitland, Chetwynd’s untrammelled energy might be what we all need.

*William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland until 19 February 2017; Marvin Gaye Chetwynd until 8 January 2017