Art reviews: William Crosbie, Scottish Gallery | Adrian Wiszniewski, Compass Gallery

William Crosbie: The Devoted Creative, www.scottish-gallery.co.uk ****

Adrian Wiszniewski: Prudence Perched in Paris, www.compassgallery.co.uk ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe should count our blessings. When the plague hit Rome in 1656, people who broke quarantine were publicly executed. To judge by the crowds watching this gruesome spectacle, whatever the rules, social distancing was not one of them. If it were today, perhaps the executioner’s job would be deemed an essential occupation. His children would go to school. More cheerfully, Boccaccio’s Decameron is set during the Black Death in Florence 300 years earlier. A group of young people escaping to the country from the city in lockdown, as no doubt Boccaccio himself had done, pass the time telling stories. If our lockdown were to prove so creative, it might be some consolation. Most likely there will just be a peak in the birthrate and another in divorce. But we do have the internet and that does still gives us some access to art. Several galleries have put their shows online and so, although I have never before reviewed a show I haven’t actually seen, that is what I must now try to do.

The Scottish Gallery has online William Crosbie: The Devoted Creative. Crosbie is a slightly neglected figure, or perhaps better he has always been a little hard to pin down as he was a bit mercurial. He was a surrealist in the 1930s and 40s, then developed a kind of Festival of Britain cubism, a style that uses cubist fragmentation but for decorative purposes. Compotier Still-Life from around 1950 is a good example, but he went on producing works in this mode until late in life. He also painted nudes and rather lovely straightforward landscapes and still-lifes like Hampshire Harvest, or Pot of Anemones. Crosbie was born in China in 1915. He always regarded himself as in some sense Chinese although the family returned to Glasgow when he was a boy. He went to Glasgow School of Art and then to Paris on a travelling scholarship in 1935. There he studied with Fernand Léger whose influence often surfaces in his work. In Paris he also became friendly with JD Fergusson and Margaret Morris and this friendship was renewed when the couple moved to Glasgow. Fergusson is visibly an influence on much that Crosbie did thereafter.

Crosbie died in 1999. This show is from the artist’s studio and so is mostly later work. Nevertheless, there is a charming drawing of a woman at a Paris market from about 1938 and, from around 1941, a drawing of the avant-garde Polish artist Jankel Adler with friends in Crosbie’s studio. Adler, a refugee whose work had featured conspicuously in the Nazi Degenerate art exhibition, was briefly an electrifying presence in Scottish art and this drawing is a fascinating record of that time. A portrait of TJ Honeyman, later director of the Glasgow Art Gallery, is an important memento from the same milieu. The patterned fabric behind the sitter suggests that Fergusson’s radical painting, From My Studio Window, was available in the painter’s studio as inspiration.

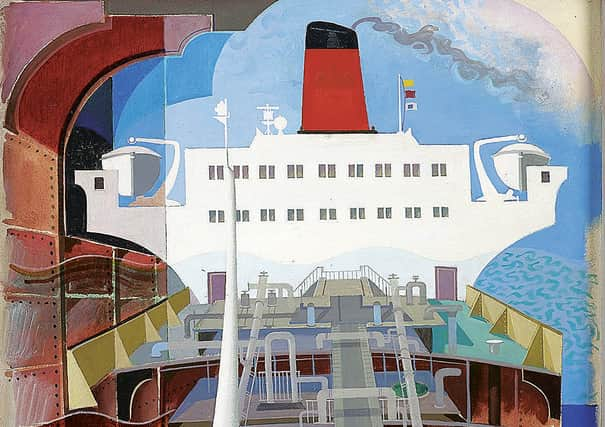

Much later too there is a homage to Fergusson in Cathédrale à l’Huile, a part cubist and part cut-away image of an oil tanker. Fergusson maintained the shipbuilders of the Clyde were like the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages. One other thing that Crosbie shared with Fergusson was a love of the naked female form. Voluptuous nudes are a striking feature of his work. There’s a lot of what Mary Beard would disparage as the male gaze about them, but that is a piece of cant that thinly disguises the dismal Victorian attitude to sex as a rather nasty male weakness, not a mutual delight. However unfortunate it may seem to some, a male painter can deploy no other gaze. But delight is what informs Crosbie’s nudes and they show him as a painter at his most frank and at his best.

The radical impulse that Fergusson brought to art in Glasgow in the 40s and to which Crosbie bears such eloquent witness endures in one remarkable institution, The Compass Gallery. Cyril Gerber, who founded Compass in 1969, was inspired to do so by Tom MacDonald, a painter who like Crosbie was very close to Fergusson and indeed his work has much in common with Crosbie’s. Cyril died in 2012 aged 94, but his daughter Jill has kept flying the flag for good art in Glasgow in the face of considerable adversity.

The latest Compass show is Prudence Perched in Paris by Adrian Wiszniewski. The show includes a variety of work and some of the artist’s most recent, lush landscapes, but always with Wiszniewski there is a striking new departure and in this show it is a group of works using white line against black. Woman

with Cats and Woman with Lizard II are beautiful examples. They combine Matisse’s line with a kind of Ad Reinhardt minimalism, though they also remind me of Eric Gill woodcuts, but, as ever with Wiszniewski they are both original and surprising.