Art reviews: Sean Caulfield: Firedamp | Archipelago | Process and Possibilities | The Print Show

Firedamp ****

Edinburgh Printmakers

Archipelago ****

Summerhall, Edinburgh

Process and Possibilities ****

Edinburgh Printmakers

The Print Show ****

Fine Art Society, Edinburgh

Firedamp is a flammable gas found in coal mines and a menace to miners. According to Wikipedia it is found “particularly in areas where the coal is bituminous” – the tar sands of Alberta in Canada, perhaps. Print-maker Sean Caulfield hails from Alberta. Firedamp is the title of his show at Edinburgh Printmakers and he himself makes the connection with the controversial tar-sands of his home. His subtitle, however, is Revisiting the Flood, suggested by the catastrophic tsunami that flooded the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan. That is a personal link too, he says, for his wife’s family live in Tokyo. Nevertheless his theme is not just personal. He writes about “the challenging issues ...trying to balance the needs of urban growth with the necessity of protecting Alberta’s fragile and unique ecosystems.” But his response is not entirely negative. “Crisis and change,” he says, are “a potentially positive moment of rebirth.” I wish I could share such optimism faced with the twin lunacies of Brexit and Trump.

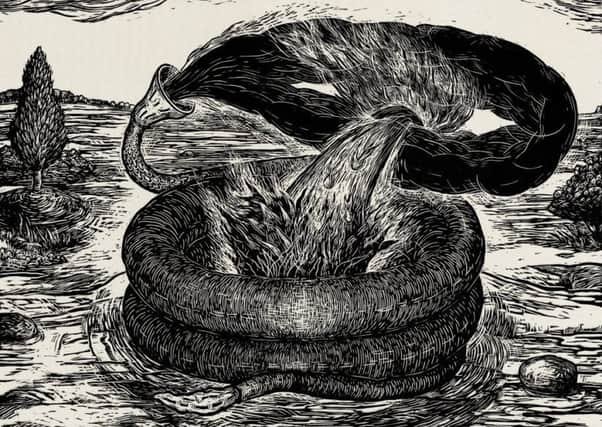

For his show, Caulfield has created a series of powerful prints and their effect is not exactly optimistic, although they do at least convey the energy that he feels might be grounds for optimism. He describes these prints as “landscapes populated by enigmatic industrial and biological forms in states of transformation.” They speak, he hopes, “of mutation, metamorphosis and regeneration.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey are certainly impressive. There are several smaller prints, but the room is dominated by two enormous black woodcuts called The Flood (Fire) and The Flood (Flooded House.) They are single images, but printed on multiple sheets and pasted onto the wall in joined sections like a poster on a billboard. The Flood (Fire), more than two metres high and twice as wide, represents a pyramid of burning sticks on a raised platform. Against enveloping blackness, the fire seems to be consuming anything living within reach. The second big print represents a wooden house floating on the flood. It looks like Noah’s Ark except that there is water inside its boundary fence higher than the water outside. Nevertheless in spite of the flood, the house, like the Fukushima plant perhaps, also seems to be on fire. It is all pretty apocalyptic and the starkness of woodcut’s rough white drawing against dense black reinforces the drama. The way the prints are pasted to the wall adds further urgency. There’s nothing precious about these art works, it says. They are as expendable as billboards would be, and like them, it is the message that counts.

A three-handed show at Summerhall also takes the crisis of the modern world as its starting point. Called Archipelago it brings together work by David Blyth, Alan Grieve and Derrick Guild. Jon Blackwood has brought these three artists together, arranged the show and written the introduction. I will avoid the word “curated” here. You can have a sandwich curated in New York and the contemporary need to foreground the curator is generally only an attempt to ascribe meaning to art that has none. It is also a symptom of the creeping managerialisation of the arts which Blackwood himself sees as a symptom of their decline. Spending time in the Balkans, the fissiparous heirs of the once unitary state of Yugoslavia, in his introduction he is moved to reflect in a rather melancholy way that the parlous state of the arts in those places, where substantial public support was once guaranteed but is no more, is a grim prophecy of our own future. Looking at contemporary art from a Balkan perspective, he writes, “it seems far less likely that contemporary art structures from there will replicate those of a country like Scotland than it is for the art world of Scotland in the future to resemble the current situation in the Balkans.”

So Scotland will be the new Balkans, pushed once again to the edge of Europe with England obstinately placed between us and our neighbours. It all sounds too true. Like Sean Caulfield, though, Jon Blackwood is not entirely negative. The title of the show, Archipelago, reflects his idea that hope may lie in individuals away from any imagined mainstream, linked like islands in the eponymous archipelago, and not with big centres enjoying public funds. He has chosen his three artists to illustrate this idea and up to a point, they do. David Blyth “tends to lead a private life in the remote Aberdeenshire landscape.” Alan Grieve is co-founder of Workspace in Dunfermline where “in addition to his art practice he is a much sought-after hairdresser.” While Derrick Guild worked for a while on Ascension Island, as far from the mainstream as you could hope to get.

Grieve’s work revolves around his creation of Inchfuckery, an imaginary island in the Firth of Forth. With much play on that middle syllable, cartoonish drawings and life-size cut-outs are scattered all over the walls and collaged into a film. It all looks a bit like a dysfunctional, punk version of Mairi Hadderwick’s Katie Morag and her imaginary island of Struay. It is, however, also a ribald commentary on our post-industrial and now it seems also post-truth world. David Blyth takes inspiration from the German biologist and follower of Darwin, Ernst Haeckel, to produce a series of prints that combine typography with natural and geometric diagrams. Like pages from a book, they are uniform, but also elegant. There is perhaps more than a memory of Ian Hamilton Finlay in the way he uses typography to blend word and image into a single whole.

Derrick Guild paints and makes small sculptures. These are based on the observation of nature and his paintings of a rhinoceros and of an ostrich, for instance, are beautifully executed, but he adds another dimension to his observation of the animal. Summerhall occupies the old Dick Vet School and it is largely unchanged. It even still has its name on the door and Guild ages his paintings to invoke this continuity. He suggests they are visual aids once used in the old vet school, paintings perhaps, but also humbler pictures printed on canvas that show the wear and tear of constant use. Recreating this witness to the passage of time and the way such objects – which were after all also works of art – showed how they had been used to teach generations of vets makes his rather beautiful images evocative of what we imagine was a simpler and more innocent age.

Returning finally but briefly to Edinburgh Printmakers, this is their 50th anniversary and they are running a series of small archival shows to mark their anniversary. The first, Process and Possibilities, is concurrent with Archipelago and includes work by John Bellany, William Gear, Frank Pottinger and others. Meanwhile at the Fine Art Society The Print Show takes the story back through both English and Scottish prints to Wilkie and Samuel Palmer and forward to William Wilson, Ian Fleming and Eduardo Paolozzi. William Wilson’s St Monance on view there is one of the greatest Scottish prints from any age. ■

*Firedamp and Process and Possibilities until 15 April; Archipelago until 17 March; The Print Show until 18 February