Art reviews: The Phillip A Bruno Collection | Street Level Open 2009 | Alberta Whittle & Hardeep Pandhal

A Gift from New York to Glasgow: The Phillip A Bruno Collection, Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow ****

Street Level Open 2019, Street Level Photoworks, Glasgow ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlberta Whittle & Hardeep Pandhal: Transparency, Edinburgh Printmakers ****

The season of gift-giving is almost upon us, as the shops have begun to remind us, and a gift from an art collector to a museum is an act of two-fold generosity: not only does the donor relinquish the profits he would make from the sale of the works, he makes them available to a much larger public audience than would normally see them.

Phillip Bruno, a leading New York art dealer for 60 years, has gifted more than 70 works from his personal collection to the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, the first instalment of which is now on show (a larger selection will be exhibited next year). Bruno, who will shortly celebrate his 90th birthday, has built up a long connection with the city, not least through his wife of 17 years, the Scottish art critic Clare Henry.

A co-director at the Staempfli and later Marlborough Galleries, he travelled widely in Europe as a young man, meeting artists such as Matisse, Brancusi and Giacometti and the family of Van Gogh, and built up many personal and professional connections with the American artists of the second half of 20th century. His gift is a glittering slice of American art history from abstract expressionist (and friend of Jackson Pollock) Joseph Glasco to the painstaking precision of hyperrealist Alan Magee.

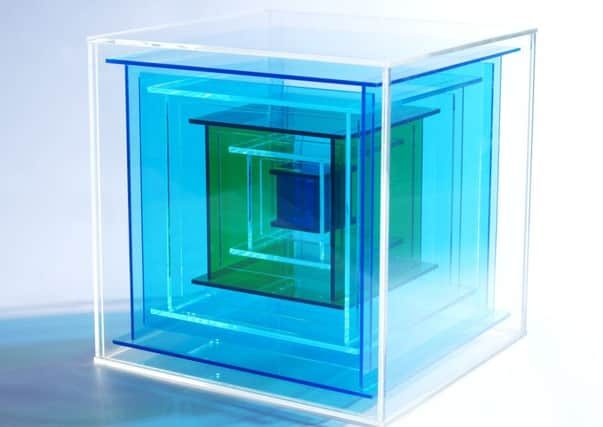

The artists here will be new to many in Scotland: Lee Gatch, William Dole, Robert Andrew Parker. There is a granite sculpture by Masayuki Nagare, who made work for the World Trade Center complex, and Tom Otterness’ maquette for The Crying Giant, the monumental figure now in Kansas City made in response to the 9/11 attacks. There is an oil study by Vincent Desiderio, a perspex box sculpture by Leroy Lamis. The longer one looks, the more there is to discover.

Like all gifts, it is personal. These works have come from Bruno’s home and from his personal connections to many of these artists. Each has a story. Now they are beginning a new phase of life in a distant country where they are an introduction, an invitation to learn more about American art, and a hint of what we might gain if we did so.

Meanwhile, at the other end of town, the Street Level Open is in full swing, kicking off a year of celebrations for the gallery’s 30th birthday. A bumper crop of 140 works by more than 60 photographers (selected from a much larger submission) brings together recent graduates, established artists and the photography enthusiasts who use the gallery’s facilities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe team has done a superb job of fitting so much work on the walls, and seeing it takes time. Much consultation of gallery notes is needed to understand how these works fit into each artist’s practice and interests. Every form of photography is here, from polaroids (Emma Newcombe) to pinhole camera (James Cadden) to the wet cyanotypes of Marysia Lachowicz, which look more like paintings than photographs.

Other photographic genres are explored from all angles, from the portraits of Victor Albrow and Izzy Leach to Peter Iain Campbell’s documentary project, Ask the Sea, about the North Sea oil and gas industry, shot from the perspective of the platform supply ships. Alex Boyd has shot a series of evocative landscapes associated with the Clearances in infrared, while retired scientist Sandy Wooton makes poetic sequences observing the dunes and rockpools of Wester Ross.

Natalia Poniatowska, doing event photography to earn a crust while studying, has found, by pointing her camera away from the main players, pictures which tell a story: the child on the floor by the buffet tables, the coloured balloons next to the toilets. Aileen Peter movingly documents the final days of her son’s terminal illness. James Carney finds those face-in-the-crowd moments when people become anonymous actors in their own lives. Indra Hilara Bylaite makes images on the theme of home, with the allegory of bee colonies. With so much work to see, it’s the stories which linger most powerfully.

There seems to be no stopping the prolific and inventive work of Alberta Whittle. While putting together her biggest solo show to date (at DCA, Dundee, until November 24), she was also, simultaneously, working on Transparencies, a two-person show with fellow Glasgow-based artist Hardeep Pandhal for Edinburgh Printmakers. For Whittle, who grew up in Barbados and is interested in issues of race and post-colonial history, the new home of Edinburgh Printmakers provided a fertile starting point. The building was once the headquarters of the North British Rubber Company which flourished making millions of wellington boots for First World War troops.

Not only does rubber have a colonial history, as Whittle points out, 25,000 Carribeans fought in the two world wars, often doing the most unpleasant jobs, sometimes without the luxury of wellingtons. Initially praised and appreciated, they saw public opinion turn against them, first in the race riots of 1919 which occurred in several UK cities including Glasgow, and more recently in the political backlash against the Windrush generation.

Her films, What Sound Does The Black Atlantic Make?, made for this show, and her 2018 film Sorry Not Sorry, weave these themes between past and present, from Kitchener to Carribean beach holidays, from singer and activist Odetta Holmes to David Lammy’s passionate speech in parliament about the Windrush scandal. There is also a body of sculptural works and a series of new hand-tinted screenprints. But it is in the films that the ideas crystallise, and her questions about transparency – personal, political – emerge with urgency and vitality.

Pandhal – like Whittle, a graduate of Glasgow School of Art’s MFA course – takes a more ironic, even sardonic, look at transparency. His silent animation BAME of Thrones, shortly to be screened by Channel 4 as part of its Random Acts series, frames the issues in a fantasy gaming aesthetic, with lines of text reminiscent of rap lyrics. A series of etchings are informed by the work of Indian artist and cartoonist of the colonial era, Gaganendranath Tagore, taking a sharp look at the commodification of education, which continues in new forms today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile their backgrounds and perspectives are very different, Whittle and Pandhal make an interesting pairing, engaging with issues which are – sadly – all too alive in the world today.

A Gift from New York to Glasgow until 12 January; Street Level Open until 24 November; Transparency until 5 January