Art reviews: NOW at the SNGMA | Charles Avery at the Ingleby Gallery

NOW: Charles Avery, Aurélien Froment, Anya Gallaccio, Roger Hiorns, Peles Empire, Zineb Sedira, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ***

Charles Avery: The Gates of Onomatopoiea, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, the works she is showing here are about changelessness as well as decay. Next to the carpet of roses and a giant daisy chain of 365 gerberas are works in obsidian, cast metal and ceramic, works as solid and unchanging as the flowers are ephemeral.

Gallaccio is, at heart, a sculptor with a sculptor’s fascination for materials: the shiny, mirror-like surface of polished obsidian (which was used for mirrors in some cultures) draws her, as does the fact that the stone, if cut finely enough, can be semi-transparent. She uses it to make a “stained glass window” in shades of grey, a new commission for Jupiter Artland which is being shown here for the first time.

A further room holds 27 ceramic works, the clay off-cuts of a sculpture Gallaccio made in 2014 of a mountain in Wyoming, selected and fired in a coal-fired kiln in the Highlands using a variety of glazes. They are strange, evocative forms, some metallic, others like earthenware, others like joints of petrified meat.

Gallaccio is also fascinated by processes: the semi-accidental ones, like the clay off-cuts; traditional ones (she has made marbled papers using samples of rocks and minerals from different states in the USA) and scientific ones (photographs of rocks and soil made using an electron microscope look like lunar landscapes of mountains and canyons).

She is interested in how materials are transformed, by process and by time itself.

This means her work is inherently experimental and results vary – some works have more resonance than others. Perhaps the red roses are overburdened with meaning to the point of cliche. But her cast of a sapling in bronze, The Whirlwind in the Thorn Tree, is a beautiful conundrum, a thing which intensely resembles a living tree and yet is so lifeless – indeed the process of casting it killed the living original – that it succinctly captures so much of what art tries to do, both how it succeeds and how it fails.

Each NOW show draws in a number of other artists who share aspects of the central artist’s interests, directly or tangentially. It’s easy to see the connection with French-Algerian artist Zineb Sedira, whose photographs of unprocessed sugar in warehouses in Marseille are deeply sculptural, and whose sculptures made of cast sugar cane sparkle with a cold charm. Sedira’s use of materials is also political: she is drawn to sugar not only for its sculptural qualities but because of its long history with displacement and slavery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdinburgh-based French artist Aurelien Froment demonstrates an eye for materials in his rope sculpture which loops around the walls of a dark room. However, it shares the space awkwardly with his 2018 film, Apocalypse, which takes its imagery from the medieval Tapestry of Angers and its strange text from the Canadian poet Steven McCaffrey, and seems to reach towards a very different set of concerns.

Roger Hiorns works with materials with his “painting” made of copper sulphate crystals, and “drawings” made using bovine brain matter. Three objects from his Youth series – an X-ray machine tipped on its side, a jet engine and a park bench – are “activated” once a day by the presence of a naked youth who comes into the space and lights a small fire. His presence transforms these objects, making them look like artefacts from a past age rendered obsolete by his youth and vitality.

But perhaps the most unexpected work here is Charles Avery’s 16mm film, Untitled (Dihedra), which shows two butterfly-like forms fluttering around inside (and occasionally outside) a cuboid metal frame. Avery’s current work is part of an ongoing series, The Islanders, and seeing a work like this in isolation is a reminder of how abstract he can be, how mathematical and how cleverly suggestive of a wide range of meanings.

We are more used to seeing Avery’s work in instalments which continue to broaden our understanding of the world of The Island, his invented country which is one part Hebrides, one part East London, and several parts his own boundless imagination, and the latest of these, The Gates of Onomatopoeia, is currently on at Ingleby Gallery.

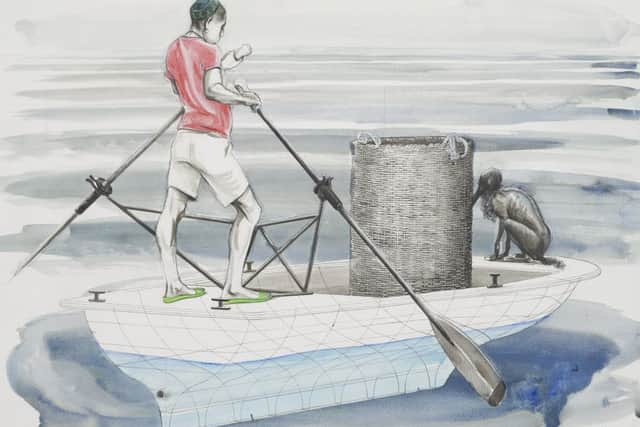

The Island is richly imagined and explored in Avery’s fine drawings and sculptures, but is also a space in which he can depict philosophical and mathematical questions through more abstract works. In this show, he continues to evoke this other world with atmospheric drawings of animals scavenging in the market at night, and louche young radicals shooting the breeze outside the Union Cafe. But there are two really major works here: a large drawing depicting the twin-towered seaward gates of the island’s capital, and a sculpture of the Union Tree which occupies the centre of the gallery.

Both of these are rendered with geometric precision. The tree (The Islanders like their trees to be geometric) is made of metal and glass, an exemplar of Euclidian geometry and sculptural balance.

But surely it is no coincidence that Avery is occupying himself with barriers, borders and gateways at a time when our own country is obsessed with them. Nor, surely, is the word “union” accidental. Avery might, for a good part of his time, live in his own world, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t got his finger on the pulse of ours. - Susan Mansfield

NOW until 22 September; Charles Avery until 13 July