Art reviews: NOW | Franki Raffles: Observing Women at Work

NOW at Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

Franki Raffles: Observing Women at Work at Reid Gallery, Glasgow School of Art ***

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

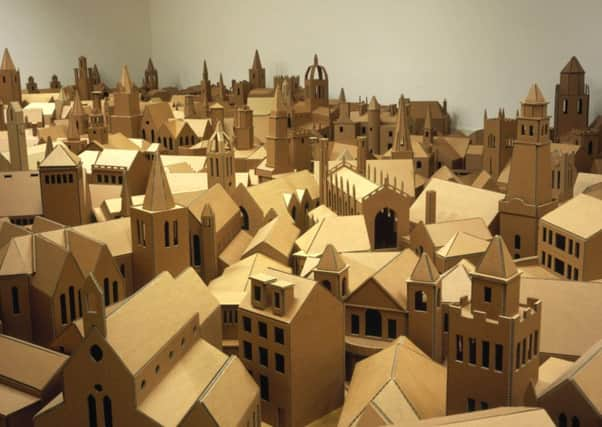

Hide AdA good work of art is more than the sum of its parts. Nathan Coley’s The Lamp of Sacrifice, 286 Places of Worship, first exhibited at the Fruitmarket Gallery in 2004, is a set of cardboard models of every building listed as a place of worship in Edinburgh in the Yellow Pages at the time, no more, no less.

But by making something precise and clinical, Coley has created a work with much greater resonance. It sits in the gallery like a quiet congregation of the still-faithful in an age of rampant secularism. Grand buildings and ordinary ones are equalised by a common material. Now remade, after sustaining water damage, it is a snapshot in time: some of these buildings have changed in 13 years; even the Yellow Pages is no longer what it was.

The Lamp of Sacrifice is the centrepiece of the first exhibition in a series called NOW at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, aiming to showcase contemporary works in the permanent collection by placing them in the context of other work by Scottish and international artists. This show is the first of six, each of which will have at its centre a body of work by a single artist.

Here, the Lamp of Sacrifice is flanked by two newer works by Coley, wooden scale models of St Paul’s Cathedral and Tate Modern which are open at one side, like doll’s houses or curiosity cabinets, and house a selection objects, pictures and books. Normally so neat as to be almost minimal, Coley allows these objects to collect together more casually, laden with associations from history, from the Blitz to the Occupy movement to Ed Ruscha’s painting from the 1960s, LA County Museum on Fire. In separate rooms, on either side of The Lamp of Sacrifice, they balance one another, baroque and industrial, sacred and secular, both grand institutions in pursuit of meaning situated in the midst of a third.

If the principle of The Lamp of Sacrifice holds true, compile enough mundane detail obsessively and present it in the right way and it can become much, much more. Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander gathered 365 shopping lists from local supermarkets during a residency in London in 2013-14, and presents them like a calendar, a portrait of everyday life, each one as individual as its writer, from the scribbled back-of-an-envelope to the meticulous computer print-out.

Her ten-minute film, The Tenant, made with Cao Guimarães, of a bubble floating through an empty apartment, negotiates place, the other major theme of the show. At first, one fears it will burst almost instantly; when it doesn’t, it starts to look indestructible, an alien presence with sinister overtones. Glasgow-based artist Tessa Lynch’s Wave Machine explores what it means to navigate the city as a female flâneur through photographs, a text conversation and evocative sculptures inspired by broken umbrellas.

Pete Horobin is another obsessive documenter. The Dundee-based artist, who has made work since the 1980s under a series of personae (he is currently “ae phor aitch”), feels like a significant presence in Scottish contemporary art, albeit one who has operated largely beneath the radar. Work recently acquired by the National Galleries is exhibited here, including documentation of a journey made in the persona of The Acrobat, and three complete years from the 1980s from his ‘Attic Data Archive’: documenting each day in photographs, found materials, records of his vital signs. Both overwhelming and fascinating, these were made long before social media turned us all into obsessive documenters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLouise Hopkins and Tony Swain are obsessives too, in their way, both working on found paper surfaces, disrupting and transforming the original. Swain uses newspaper pages which he turns into painted landscapes, with a heavy dash of surrealism. Hopkins is capable of being both playful and profound, working on materials as diverse as wallpaper, advertisements and maps. Her 1998 map of Europe, in which the sea becomes a continuation of the land, takes on a powerful new resonance in a post-Brexit world.

There are resonances, too, in the rarely seen documentation of Mona Hatoum’s performance work from the 1980s. Informed by her experience of being an exile in Britain because of the war in Lebanon, these are raw and unflinching explorations of vulnerability and brutality. In The Negotiating Table (1983), she lies on a table, wrapped in plastic and smeared with blood, while the recorded voices of Western leaders talk about peace. More than 30 years on, with another war in the Middle-East, the works have lost none of their power. The first NOW is a powerful, careful group exhibition which allows the works to shed fresh light on one another.

The power of documenting aspects of ordinary life is more than apparent in the work of photographer Franki Raffles, at Glasgow School of Art. Raffles died suddenly in 1994 at the age of 39, and recently work has begun on examining and celebrating her legacy. A feminist and Marxist, she was also one of the founders of the Zero Tolerance campaign to highlight violence against women, highly innovative in its time, which marks its 25th anniversary this year.

This show includes elements of Raffles’ work on that campaign, next to two bodies of black and white photography showing women at work. There is a small section which contextualises her work next to images from other women photographers from the 20th century with similar concerns, but it doesn’t do much other than to illustrate that other people did this too.

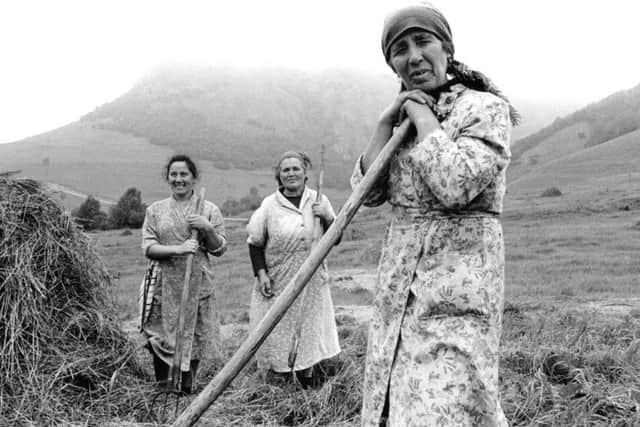

Most striking are the photographs shot during a trip to Russia, Georgia and Ukraine, in the summer of 1989. The women in these pictures are farmers, road builders, butchers, factory workers, working doing “men’s jobs” in the Communist economy, and, it seems, happy to do so; strong, feisty, no-nonsense women who are scathing about the softer world of the West. “You have people called housewives don’t you?” one asks Raffles.

The women workers shot in Edinburgh the previous year provide a marked contrast. These cleaners, laundry workers, shelf-stackers are often dwarfed by their environments, looking weary or put-upon. The series, To Let You Understand… aimed to document the realities of women’s labour in Scotland – low pay, anti-social hours, a lack of childcare, all of which have changed less in 30 years than they should.

Raffles made no separation in her work between aesthetics and politics. She wanted her photographs to say something, and they do. The strength of her Russian work is unmistakable, but the fact this was made even as the Communist ideology was collapsing also has an impact on how we see them. Unlike, for example, Dorothea Lange’s images of the American Depression, they don’t take on an aura of timelessness, though perhaps they should. They feel like museum pieces, testament to pride in a system which, hindsight now tells us, was failing, and which the postmodern world would leave behind.

NOW until 24 September; Franki Raffles until 27 April