Art reviews: Bridget Riley at the Royal Scottish Academy | Duncan Shanks at the Scottish Gallery

Bridget Riley, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Duncan Shanks: Transience, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh ****

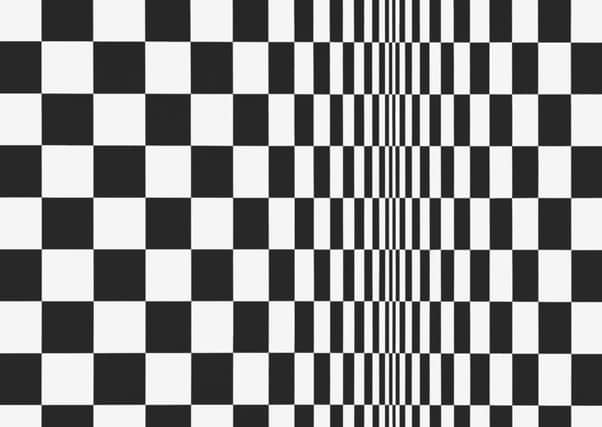

Op Art was a fashion in the 1960s: mind altering drugs, mind altering pictures. Bridget Riley was an early and very successful practitioner of the style although she eschewed jazzy, psychedelic colour and initially at least stuck rigorously to black and white. In her major retrospective at the Royal Scottish Academy you can see how dizzy-making her early black and white paintings are. Current from 1964, for instance, seems actually to heave and ripple in front of your eyes. Sixty or 70 parallel lines run vertically across the canvas in rippling curves. Where the curves are tightest, the lines get thinner. The eye reads this like perspective, as though the lines are advancing and receding. The result is a clearly visible sequence of surging crests and hollows in what is beyond any doubt a static, flat surface. In Loss, a pattern of circular black dots become increasingly elliptical. This sets up a dynamic pattern right across the surface and as the dots approach the central axis and get narrower they seem actually to flow away from us like water into some invisible opening. It is remarkable and really quite disturbing to find our eyes so easily manipulated.

The exhibition goes right back to the artist’s beginnings. There are juvenile works in one of the lower galleries and also works from her student years between 1949 and 1955, first at Goldsmith’s College in London and then the Royal College. Drawing was central both to what she learned and what she was trying to do. She copied Van Eyck and explored Matisse and Van Gogh. There are also drawings imitating Seurat’s drawings with black conté crayon and the earliest work in the main part of the show is a copy of a Seurat painting. She was deeply engaged with his art. Indeed there is an essay by her in the catalogue entitled Seurat as Mentor. His pointillisme, his way of painting with dots of separate colour, proposed that the surface of a painting is not merely passive. It can be dynamic and with this energy facilitate a creative partnership between the artist and spectator. This is always the case of course, but isolating it and making it a conscious goal for the artist was the cue that Riley took from her great predecessor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was more to it of course. She was very much of her time. In the late 50s, the pioneers of Op Art were artists like Victor Vasarely and Josef Albers, while a series of major exhibitions brought the art of the American Abstract Expressionists to London. Among them Jackson Pollock presented Bridget Riley with the example of a big canvas, dynamically articulated right across its surface. She has never been tempted by his freedom, however, nor indeed by freedom at all. Studies and working drawings show her constructing her paintings painstakingly on graph paper. She is and remains an intensely controlled artist.

In some of her dizziest black and white works, we already think we are seeing colour and she soon moved on to colour. In Drift 2 a set of vertical wavy lines vary in thickness to create the ripple effect. The white also darkens progressively until it merges with the black at the edges. But here, reinforcing the optical illusion of suggested colour, she hints at a shift from cool to warm in the black and from grey to blue in the white. The whole surface curves as a result. In the wavy surface of Cataract from 1967 across the centre of the picture, black stripes shift to bright red and blue.

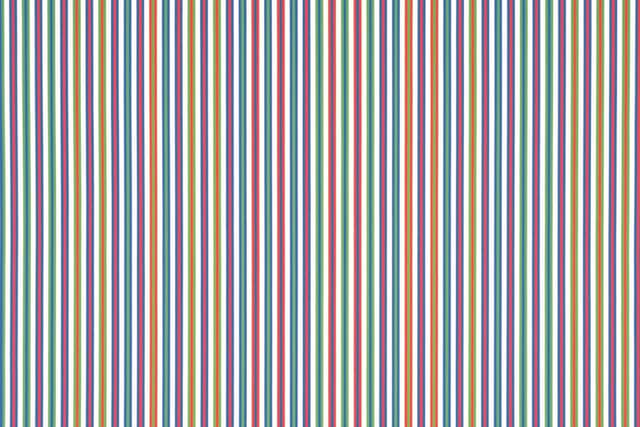

When she moved on into pure colour, initially she used simple stripes with a limited group of colours, repeated but shifting their relative positions. Clepsydra combines this arrangement with a wavy lines composition to great effect. In Rise, she uses the three secondary colours, violet, orange and green, in changing groups of three separated by bands of white. In a room dedicated to her studies, she sets out seven variations on this composition with a commentary explaining how the shifting position of the violet creates a sense of upwards movement. It is however much more subtle than the in-your-eye impact of her earlier work.

Indeed, her approach to colour is as austere as her use of black and white, but without the fun and games. It was only in the late 80s that she introduced a new dynamic by running bold diagonals across vertical stripes. Sometimes the diagonals are contained by the verticals. Sometimes they overlap and cut across them. The result in Justinian, for instance, is a progress of rattling urgency from left to right. One of Mondrian’s Boogie Woogie paintings is illustrated in the catalogue and there is certainly an affinity, though if his picture is a dance, hers is only a march.

Photos of her at work suggest she took a lead from Matisse and laid out her compositions with cut-out paper. Without his vivid sense of improvisation, however, her scissors are less lyrical than his. Nevertheless, when she introduces sweeping curves into her diagonals as she does in Red with Red Triptych, a big picture in pink orange and blue whose three parts are separated by areas of wall, Matisse’s painting, La Danse, is invoked directly. The same image is hinted at in Rajasthan. Painted directly onto the wall, though not by the artist, the white wall becomes the space through which it moves. Returning, now in her late 80s, to the inspiration of her early years, she has also recently worked again in black and white. The wall painting, Quiver 3, for instance, is composed of black triangles against white, linked at the corners and organised in three groups. Some triangles are plain isosceles, some have one curved side. All are the same size. The result is economical, extremely elegant but also dynamic. Here and in a related small painting called Harlequin,

but also in the wall painting, Rajasthan, the white wall, unconstrained by any formal geometry, introduces a sense of freedom. No graph paper here, a little joie de vivre breaks through the stern discipline that is such a feature of so much of what she has done.

Duncan Shanks, whose show Transience is at the Scottish Gallery, is five years younger than Bridget Riley. Coming of age as a painter at much the same time, he started from similar inspiration, but he chose Van Gogh and freedom rather than Seurat and formality and so was more directly inspired by the Abstract Expressionists. As a result, his painting could not be more different from hers, except in one thing: both artists are concerned with the dynamic. Life will never stand still to be painted, so some other strategy has to be devised. For Shanks, it is the restlessness, the constant change even in the most familiar things (the transience indeed as life flows by like the River Clyde past the bottom of his garden) that it has been his mission to try to convey. This he has done with consummate success in paintings like Moonlight and Moths, or Rage Against the Dying of the Light. They don’t jump around in your eye, but the energy of life is in them all the same. n

Bridget Riley until 22 September; Duncan Shanks until 26 June