Art review: Summerhall

Various of the art projects in Edinburgh this summer respond to the 70th anniversary of the Edinburgh International Festival, and the post-war moment in which it was established. The wide-ranging programme of exhibitions at Summerhall, which runs until 24 September, takes its title from one of the festival’s original aims, “To Heal the Wounds of War”.

To what extent art can heal is an interesting question. One artist who believes it can is Alastair MacLennan, a Scot who settled in Belfast in 1975 at the peak of the Troubles, and whose practice has become deeply interwoven with that conflict and its aftermath. MacLennan’s exhibition, Air A Lair (JJJJ) captures his belief that there is something in art which is transformative. When he lays a long banqueting table and scatters it with the names of those who died in the Troubles, or makes a work like Body of (d)Earth, a table laden with earth and a burned beam of wood, he is talking about war and loss, but is bringing something to it – dignity or grace, perhaps – which both honours the subject matter and makes it easier to bear.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike many artists who work principally in performance, MacLennan distrusts exhibitions of documentation: the work exists in the moment. Nevertheless, this is a rich show reflecting more than 40 years of practice: drawings, which are rarely shown, slides of earlier performance works shown on light boxes, installations (his pile of pairs of spectacles is powerfully reminiscent of the piles of shoes and clothing in the Nazi death camps), and a new film by Richard Ashrowan, which captures the meditative qualities of the work.

The four rooms form a kind of modest retrospective, a quiet, meditative space in monochrome shades. More space would be helpful, as would a little more supporting material to help people who don’t know his work to find their way in. But if one spends time here, one begins to feel the effects of MacLennan’s Zen philosophy, the balancing of opposites, the valuing of fragments, and a reflective attentiveness from which a kind of healing can come.

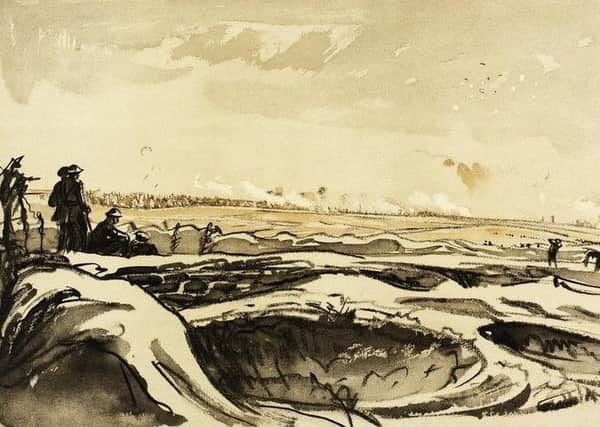

The earliest works at Summerhall are a selection of drawings by Muirhead Bone, from the Western Front (JJJ). Bone was Britain’s first official war artist, sent to the Front by the War Propaganda Bureau in August 1916 when the Battle of the Somme was at its height.

He was a fine draughtsman, and these images are restrained but powerful: barren fields and blasted trees; the ruins of bombed-out buildings; warehouses of ordnance stretching into the distance; officers sitting down to tea and in a tent with a milk jug and sugar bowl; squaddies in a trench with their rifles aimed. They are not reflective works, they are produced in the midst of conflict, a unique record of a time which we cannot now view without the weight of hindsight, wondering what horrors he might have witnessed and did not draw.

In the basement, a fascinating exhibition brings to light a remarkable character who has all but slipped from history, Rudolph Von Ripper (JJJJ). “Rip” was an Austrian aristocrat, soldier and artist, imprisoned and tortured in 1934 for his opposition to Hitler, who later became an American spy. His story is told in the book Von Ripper’s Odyssey: War, Resistance, Art and Love by Sian Mackay, after the chance discovery of a file of letters and photographs at a villa in Mallorca where he once lived.

Shortly after his release from prison, Von Ripper produced his masterwork, a suite of 16 richly allegorical prints titled Ecraser l’infame (to crush tyranny), referencing Goya, Dante, and perhaps even Hieronymous Bosch (one print shows Hitler in a desecrated cathedral playing a pipe organ while torture victims dangle from a Catherine wheel overhead). A passionate polemic about the horror engulfing Europe, the prints were shown in London in 1935 and promptly condemned by Germany as “an insult to a friendly state”.

A country working through a recent experience of war can be witnessed in Return: In Search of Stillness (JJJJ), which brings together more than a dozen artists from, or with connections to, Sri Lanka’s Colombo Art Biennale. The event was launched in 2009 when the country was in the throes of civil war – the first show was called Imagining Peace.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe shadow of that war is still very present in the work: Vijitharan M’s work concerns women who went into labour during the conflict, and those who were “disappeared” whose families still wander “broken and tearful in the street” forgotten by the rest of society; Abdul Halik Azeez’s photographs from the series The Violence of Memory and Maya Bastian’s film Post-Memory examine how the traces of war persist, even in a new generation.

This exhibition captures a mixture of responses to war: the imperative to remember and archive, as in Radhika Hettiarachchi’s Herstory; Pala Pothupitiya’s work with maps asking questions about nation states and their symbols; Anup Vega creating a space for reflection, and for bringing together rituals from different traditions. There is also a further exhibition including work by 21 European artists who have been resident at Sura Medura, the arts centre and artist residency project founded with Scottish support in the wake of the 2004 tsunami.

This Time in History, What Escapes (JJJ) is part of a continuing project by Edinburgh-based artist Rose Frain, creating room-sized installations which recall moments in recent history. The room shown here is concerned with Afghanistan and draws on a wide range of references: trail rations and survival kits from the UK military; minerals, including gold, lapis lazuli and copper, which are mined in the country; Chelsea Manning, who leaked Afghan War Logs to WikiLeaks; “Marine A”, a British soldier convicted of murder of a Taliban fighter (the charge was later reduced to manslaughter under the Geneva Convention).

The work consists in objects and fragments displayed in locker-like cabinets and a museum-style glass case, each carefully considered and adding new elements to the story. There is a blue burka on the wall, and an installation of heliographs – reflecting mirrors used by troops for emergency signalling. However, while each object is laden with meaning, it requires time and information (perhaps more than is available here) to decode them, and understand and how this intricate collection fits together.

Scottish artist Jane Frere’s #Protestmaskproject is as immediate as Frain’s work is considered. Using the iconography of the now universal CAT mask (Creative Aesthetic Transgression) it feels like a scream of rage at recent events: the election of Trump, the Brexit vote, the concerns about cyber privacy which affect us all. Frere, whose moving Return of the Soul project was shown at Edinburgh Art Festival in 2008, here creates a work which is louder and angrier, inviting viewers to don a CAT mask (available from the Summerhall shop) and take the protest around the world on social media.

Another work which feels like a gut response is the work of Protestimony: We need to talk about Calais, who have recreated a section of the Calais Jungle in a group of portacabins in the courtyard. The Jungle was home to more than 6,000 refugees and migrants before it was cleared by the French authorities last October. Lujza Richter and Marthe Chabrol display material made during art workshops they ran in the camps, adding research, statistics and installations which mirror the makeshift Jungle dwellings. It’s shambolic, rich and vital, a straight-from-the-heart response to a situation which hasn’t gone away, and where healing is still a long way off.

All exhibitions run until 24 September