Art review: Michael McVeigh at the Scottish Gallery

McVeigh was born in one of the least privileged parts of Dundee. School was evidently not of much use to him. He reckons he was “brought up in a zoo”; he got more of an education volunteering to look after the animals, including an unhappy bear, at Camperdown Park in Dundee. He then took himself quite unofficially and with no qualifications at all to classes at Dundee College of Art where he was discovered – tutor James Morrison and Head of Department Alberto Morrocco together reckoned that his drawings were qualification enough and he had to stay. Tutor John Johnstone took a particular interest in him and with his encouragement he completed the course. A little later a trip to the National Gallery in Edinburgh proved life-changing and since then he has made the city his home.

.

The Romanticism, Folklore and Fantasy of Michael McVeigh ****

Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

.

Baldwin and Guggisberg: The Cathedral Collection ***

St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh

.

Jenny Matthews: Sapphire Skies ****

Union Gallery, Edinburgh

.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

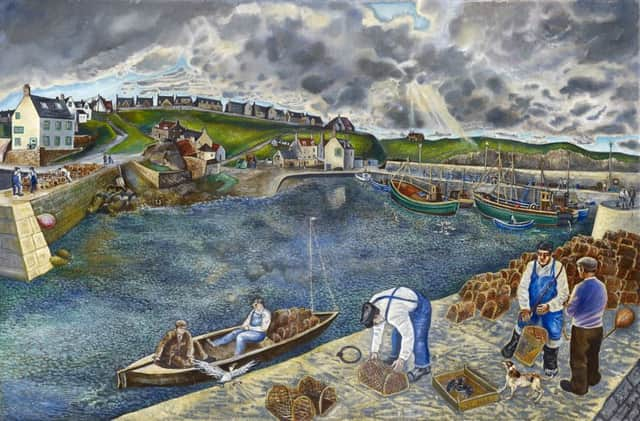

Hide AdThough he has worked all over Scotland, the capital has been the subject of some of McVeigh’s most memorable pictures and features prominently in the current show. On the face of it, his style is naive, but, like the Douanier Rousseau before him, whose work his own often resembles, that is a superficial impression. Any close examination soon reveals a complicated exchange going on between sophistication and naivety. In the Scottish Gallery show, for example, a big and very fine painting of St Abbs Harbour done not long after the artist had finished at art school shows that he had learnt a lot there. The water sparkles and the sky in particular is an accomplished study of moving clouds and dramatic light and shadow. Later, however, he simplified his style. In a recent picture of Edinburgh under snow, Looking to the Castle, Winter, for instance, the snow on the roofs of the buildings emphasises the simplicity of their shapes, but the way they are stacked together and the nice balance of light and dark, warm and cool, together make a very satisfying composition. It has all sorts of echoes, too, reaching back to the early renaissance and revealing real familiarity with the great art of the past while nevertheless also feeling distinctly modern. Always alert for a striking image, in Cow Parsley, London Road he catches a moment in spring when the cow parsley makes a sheet of white under the trees, its feathery texture invoked with a lightness of touch that would not have shamed Monet.

He works indoors as well as out of doors and paints people in the bars of Edinburgh and Dundee with a real feeling for atmosphere. There are all sorts of things going on his pictures, too. In The Royal Wedding, the Royal Mile, he transported the wedding of Kate and William to Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. The wedding procession is complete with pipers and a golden coach, but bizarrely a large cow and a goat are also in attendance. Even more surreal She is the Harbour shows a naked woman curled into the curve of a harbour’s sheltering arms and holding up a mirror to herself, all against a deep blue, abstract sea.

Nor does he stick to the present. Pilgrims at St Andrews shows a priest and cardinals greeting the faithful with the great cathedral restored to its former glory. One of the oddest images, The Penny Hing, is also historic. It shows the most rudimentary support offered to the drunk and indigent. For a penny they could lean on a rope. For Tuppence they could sleep in a box.

His painting is supported by his beautiful, elaborate, but never laboured drawings. One of the finest of these shows the former harbour at Prestongrange restored, but also deep underground and indeed under the sea, miners are labouring in the tunnels far below that eventually undermined the harbour. The intricate observation of the small figures in drawings like this shows how much real skill underlies the apparent simplicity of his art.

Cathedrals feature more than once in McVeigh’s art, but St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral in Edinburgh is actually the site of an exhibition, The Cathedral Collection of glass by Philip Baldwin and Monica Guggisberg. Apart from a great window by Eduardo Paolozzi, the glass in St Mary’s is not really notable, so in principle this show put on by Gallery Ten is an enhancement for the glass installed throughout the church.

As you enter, a tall mobile of small spheres and lozenges of glass in various colours and degrees of opacity greets you hanging in the nave. I can’t say that this or other similar installations hugely enhance the church, however. Modern art in religious buildings is notoriously tricky and the success of Paolozzi’s window is unusual. More successful than some of the other current installations though is Voyage in the Rain, a composition in a golden boat of flasks and funnels of glass whose colour discreetly endorses the Victorian window above. The best piece is another boat, this time full-size, filled with big flasks in plain glass and called the Long Voyage, a visual pun, perhaps, on the notion of each of us leading our lives from birth to death, worthy or unworthy, as a vessel for the divine within.

The Union Gallery has moved from its site in Broughton Street to Drumsheugh Place and so is now just round the corner from St Mary’s. The current show there is of watercolours by Jenny Matthews. That she is a sometime pupil of Elizabeth Blackadder is readily apparent in beautiful flower studies that echo those of her teacher. That in itself is no bad thing, but there is more to her work too, however. A beautiful, freely painted vase of flowers called Little Bouquet, for instance, has a freedom and delight in its subject more reminiscent of John Maxwell, while the handling of stone walls and the doors of an ancient French barn as background in other studies, still primarily of flowers, show real skill in evoking the weathered sense of time to which such things bear witness. ■

Michael McVeigh until 1 October; Philip Baldwin and Monica Guggisberg until 19 September; Jenny Matthews until 12 September