Art review: Margot Sandeman | David Michie | Matthew Inglis

But Eardley was not the only artist with whom she was associated and whose greater fame has tended to dim her own. She was also a long-term friend and collaborator of Ian Hamilton Finlay who was also briefly a contemporary at Glasgow School of Art, and that too has tended to dictate how she is remembered.

Now, however, Sandeman is the subject of an exhibition at Cyril Gerber Fine Art in Glasgow. The show includes a substantial number of paintings and a few drawings, but it is nevertheless not a retrospective. The great majority of the works are relatively recent, dating from the 1980s onwards. There are only a tiny and rather tantalising handful from earlier in her career. Among them, one dark but accomplished painting called Lovers in a Barn dates from the very beginning of her student days. It shows a couple embracing in a shadowy barn while a flock of sheep in the foreground look the other way.

Margot Sandeman: A World of Visual Poetry ****

Cyril Gerber Fine Art, Glasgow

David Michie – Studio Works ****

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

Matthew Inglis: The Butterfly Effect ****

Edinburgh College of Art

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is also a double portrait of the artist with Joan Eardley from 1960. Its rough handling suggests the artistic relationship between the two as much as the picture suggests their personal relationship. Though it may be unfinished, it is, however, perhaps more interesting as a document than as a painting. Later a very different mood prevails. The Poet’s Dream from 1974, for instance, is a warm landscape with a hint of Samuel Palmer as a poet-shepherd reclines contemplatively beneath the moon. Wild Roses is imbued with the same exquisite pastoral mood. The dreamy subject of this latter painting with a figure reclining beneath a rose bush points towards the elegiac mood of her later work.

In Figures with Guitar from 1980, for instance, three somewhat androgynous figures with books and guitar languorously populate a woodland scene. The dominant pattern of the leaves already shows the rhythmic, formal style which characterised her later work. It is reminiscent of Van Gogh, but the mood is tranquil and the effect decorative. Idyllic scenes of figures in nature seen in paintings like Bathers by a Burn, Figures on a Hillside, or By The Shore recall the seaside idylls of painters like Maurice Denis, Signac and the early work of Matisse, all working on the shores of the Mediterranean at the beginning of the last century. Matisse certainly remained an important influence on her work.

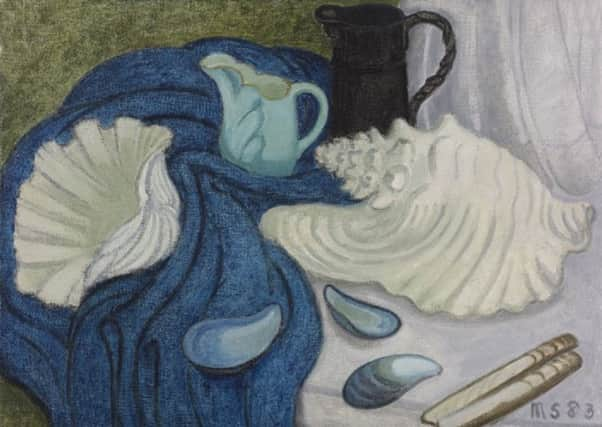

Still life was also a constant subject and her formalised style and vivid colour works well in paintings like Cherry Laurel and Bluebells and White Jug. The works she did with Ian Hamilton Finlay are a series in which still-life is combined with the text. One of his aphorisms or definitions and a chosen piece of poetry or prose are collaged into the painting as though part of the still-life. Red Currant, for instance, shows boughs of the fruit against black and white cloths and a turquoise dish. The text includes Finlay’s definition of the red currant as the Scottish vine. Jug is another lovely example of this collaboration. Finlay supplies a characteristically whimsical double definition as both a “fluted column crowned with ellipses” and “the note of the nightingale.” In the picture, a fluted white jug, like a classical column, and an enamel candle stick with bright blue edges sit together on a shelf with the text behind the candlestick seamlessly incorporated into the composition.

The late David Michie was another artist who had to work a little harder to make himself visible against the brighter light of another artist. His mother was Anne Redpath, but a two-part exhibition at the RSA demonstrates how successfully he carved out his own artistic language all the same. The exhibition consists of work gifted by the family to commemorate his long association with the Academy, following that of his mother before him, and of work from his studio. The paintings in the gift show his work over a period of nearly 50 years. A charming picture of the patterned brick façade of a tenement in Gardner’s Crescent, Edinburgh from 1964 is among the earliest dated works on show and a coolly beautiful painting of tulips from 2010 is among the latest. The quirky observation of the flowers in the windows and the curtains of Gardner’s Crescent and the comically observed figures half hidden by a wall in Portuguese Conversation, also from the Sixties, already point the way he was to go. He can carry off a big set piece like the vividly coloured Suffolk Road Back Garden, but you feel the man himself more in the delicate observation of a crow’s nest on a Shetland telephone pole, of a great northern diver, or the gentle humour of naked figures frolicking on a beach in Frolic. He observes dancers and figures in a street procession with the same humour and a touch so light that it is almost self-effacing, as though he would rather the delicacy of his observation could speak for itself.

If the work of Matthew Inglis is unfamiliar, it is not because it has been hidden behind some brighter light, but simply because it has not had the exposure it deserves. The Butterfly Effect in the Andrew Grant Gallery at Edinburgh College of Art now helps to put right that injustice. This is a substantial and intriguing show. It consists of black boxes, each one containing a strange, surrealist tableau. Most are single, but some are in pairs or in series. Many are humorous. Thinking outside the Box, for instance, a box in a box, is a simple visual pun, but there is also an underlying seriousness in many of the works. Everything Has a Price, for instance, shows butterflies with banknotes for wings, a centipede with a price tag and leaves with barcodes. The eponymous Butterfly Effect is a double-take composed of two boxes both with big black bombs falling through cotton wool, Magritte-like clouds against blue skies. In both boxes, the weight of the bombs is contrasted with a single coloured butterfly sitting on a fluffy cloud. If a single butterfly could ultimately destabilise the world, how much more could thoughtless, heavy-handed human activity? ■

Margot Sandeman until 28 September; David Michie until 6 November; Matthew Inglis until 30 September