Art review: Leonardo da Vinci : A Life in Drawing, Queen’s Gallery, Edinburgh

The artistic richness of drawing is self-evident, but more than that it is also astonishingly useful. With it we can investigate, analyse, record and communicate information; we can develop, project and examine ideas and much more, too. I would argue it was the single most important instrument in the rise of the scientific and technological culture that for better or for worse defines the modern world.

Leonardo da Vinci : A Life in Drawing, Queen’s Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore photography, but since then too, the development of medicine, the life sciences, the earth sciences, everything and anything technological or mechanical, all depended on drawing. It is as old as the caves of course, but it was the recognition by the artists of the Renaissance of how precise drawing could gather and communicate information about the physical world and be a primary instrument in understanding how it worked, that was distinctive.

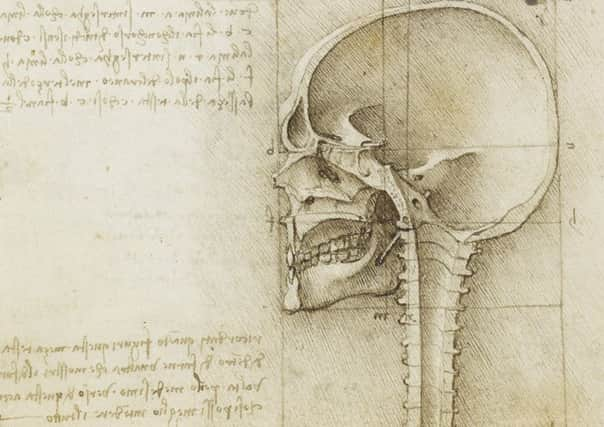

The breakthrough happened in the 15th century in Flanders with the Van Eycks and their contemporaries, but it soon caught on in Italy too. In the exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: a Life in Drawing, a lily drawn by Andrea del Verrocchio demonstrates just how skilled the artists of Renaissance Florence had become by the mid-1460s when, at around the age of 14, Leonardo became Verrocchio’s pupil. Part of his genius was to recognise as no one else had done just what a powerful instrument he held in his hand; how he could use it to explore and perhaps understand the mysterious ways in which nature works; how by describing the anatomy of humans and animals he could even investigate the very mechanics of life itself. His was the genius of prescience, for this was more than a century before the nascent scientific communities of the early 17th century began the story of modern science using exactly the same means. One of their first great projects was the paper museum of Cassiano del Pozzo, an encyclopaedia that would record everything in the known world by drawing it. It was impossible of course, but Leonardo would have understood the ambition.

The other part of Leonardo’s genius was, of course, his skill: the exquisite and often minute delicacy and extraordinary precision of his draughtsmanship are apparent in every one of the 80 or so drawings in this show. Selected from more than 500 in the royal collection, the show is part of a nationwide celebration promoted by the Royal Collection Trust to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death in 1519.

All the drawings in the royal collection came from the same source. Leonardo bequeathed the work in his studio to his pupil Francesco Melzi. After his death the sculptor Pompeo Leoni acquired most of the drawings as loose sheets. He bound them into two albums, (at least, only two are known.) One is in Milan. The other was acquired by the Earl of Arundel and then, probably as a gift, by Charles II. It is this extraordinarily short provenance and the fact that until the 19th century they were bound in a book that explains how such an unprecedented number of drawings by one artist has remained together since they left his studio five centuries ago.

It is a treasure trove. This selection is organised roughly chronologically, following Leonardo from his beginnings in Florence, through nearly 20 years in Milan working for the Sforzas, back again to Florence, to Rome, briefly shuttling between Milan and Florence, and finally to France and the court of Francis I. This semi-itinerant life-style reflected how much Leonardo was in demand for things other than painting. The diversity of his drawings reflects the variety of the work he was asked to do almost as much as his own insatiable curiosity and inventiveness.

He was a military engineer, a designer of masques and of fountains, a map maker and much else, but perhaps, too, one thing often led to another and a new task would spark his imagination. Typically when commissioned to make an equestrian statue for the Duke of Milan, the drawings here show how he designed the foundry and the casting apparatus as well as the enormous horse. (The Duke scarcely figures at all.) There is an elaborate drawing of an arsenal with men using complex machinery to lift a huge gun. Then there are designs for long-barrelled cannons in sections screwed together that suggest a keen grasp of ballistics. He drew landscapes and studied geology. Maps are a related study. They are nevertheless an unexpected aspect of his work, but there are several here. A plan of the town of Imola, which he measured by pacing the streets, is evidently as accurate as anything produced centuries later. He also mapped his own typically ingenious if rather ambitious proposal for a canal to join Florence to the sea. In a quite different artistic register, he drew emblems. A compass needle holding its direction even in a stormy sea was an emblem, or symbol, for constancy, for instance. An extraordinary, highly finished drawing of a dog in a boat and a falcon seems to belong in this category. It is so bizarre you wonder if it inspired Edward Lear to write The Owl and the Pussy-Cat. Equally mysterious, but also surpassingly beautiful, is a drawing from the last years of the artist’s life of a woman, wind fluttering her clothes and hair, looking directly at us as she points into the distance.

Leonardo’s invention was seemingly as endless as his curiosity. His drawings of dissections famously led him to anatomical insights not matched for centuries. Evidently the observations in his beautiful flower drawings are equally precise and original. In all of this activity, it is not surprising that he didn’t have much time for painting. Some lovely drawings here do relate to known though not always finished pictures, however. Drawings of an ox and of horses relate to the unfinished Adoration of the Magi in Florence. An exquisite drapery study is for the Virgin of the Rocks. In a very different mode two tiny but vivid pen sketches explore the composition of the Last Supper. Alongside are larger studies of the heads of Judas and St Philip and a superb drawing of St Peter’s sleeve.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA sheet of studies shows him working out the pose of his lovely portrait, Lady with an Ermine, but a drawing of a girl in profile seems to be drawn for its own sake. A study of the head of Leda for a lost painting of Leda and the Swan is very beautiful, but the unbelievably complex plaits in her hair seem to have particularly intrigued him. They look forward to his studies of the vortices in flowing water also included here. The Battle of Anghiari, 60 feet long, painted in Florence in competition with Michelangelo and now lost, was Leonardo’s biggest ever project. Dynamic studies of the combatants, but especially of their horses, show it was a tour de force in the depiction, not just of movement, but of pure energy. That was something he loved to try to do and it perhaps partly explains the extraordinary drawings of storms that seem to have preoccupied his last years and which close this show. Here is the world overwhelmed by angry nature. They are as gloomy and apocalyptic as you could wish in the age of global heating, but at another level, like the paintings of Jackson Pollock nearly five centuries later, they surge with primal energy. Leonardo’s envoi was to show us the raw power that art can conjure. Duncan Macmillan

Until 15 March 2020