Art review: Jon Schueler | Pat Douthwaite | Signatures of Scottish Art

Jon Schueler was an American artist who found inspiration in the west coast of Scotland. This is his centenary and to mark it Sabhal Mor Ostaig, the Gaelic College on Skye, has mounted an exhibition of his work, Jon Schueler: An Linne (The Water). When he came to Scotland, Schueler established himself in Mallaig. Situated on the Sound of Sleat, Sabhal Mor Ostaig looks across to Mallaig so it is a fitting venue, but the exhibition also acknowledges a debt. Schueler’s widow Magda Salvesen has set up a scholarship in his memory that funds an artist in residence each summer.

Jon Schueler: An Linne (The Water) | Rating: **** | Sabhal Mor Ostaig, Skye

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPat Douthwaite: The Outsider | Rating: **** | Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

Signatures of Scottish Art: Celebrating 140 years of the Fine Art Society | Rating: **** | Fine Art Society, Edinburgh

Schueler’s relationship with the west was not casual, however. He saw it as fulfillment of his destiny, the goal at the end of a long search. He was a younger member of the generation of the Abstract Expressionists, the first American artists to have an international reputation and real impact outside the US. Taught in San Francisco by Clyfford Still, who remained his close friend, as well as by Mark Rothko, Schueler moved to New York in the early 50s. There he knew all the leading artists and several became good friends. He had demons, however, and they took him away from New York just when his reputation was getting established.

He had served in the Second World War in the USAF as navigator of a B17, the Flying Fortress. He always maintained that the view of the sky through the domed plexiglass nose of the B17 was a primary inspiration in the search for wide skies that brought him to Scotland, but it was never so simple. Bomber crew losses were appalling. He belonged to the 303rd Bomber Group. Out of a nominal strength of 300 men, nearly two thirds were either killed or captured. Most of the rest were either wounded, shot down or both. Virtually all his friends and fellow crewmen were killed, but he survived. Not only was his view from an aircraft in action and so his memory of it absolutely terrifying, but also principal among the demons that drove him was acute survivor’s guilt.

At some time during the war he formed a dream of Scotland and particularly of the skies of the west coast as a place where these and other demons could be confronted and laid to rest. He may have formed this vision because it was on the west coast that he made landfall after navigating his bomber over the Atlantic, or it might have been tales of Highland scenery told him by a wartime girlfriend that fired his imagination, or even perhaps the west coast scenery in the corny but very successful 1945 Powell and Pressburger film, I Know Where I’m Going! Whatever it was, a journey to Scotland became a settled purpose and late in 1957 he left New York to find his way there. He spent a dark, cold, but very productive winter in a little cottage near Mallaig. Later he spent a summer on Skye and then in 1970 he moved to Mallaig. He lived and worked there for the next five years, returning regularly until his death in 1992. He also exhibited in Scotland from 1971 onwards.

Big spaces, though never actual landscapes, were a constant in much of the painting of the Abstract Expressionists, certainly in that of Pollock, Rothko and Schueler’s mentor Clyfford Still. Space, too, or at least spaciousness and light are what distinguish Schueler’s work. At Sabhal Mor Ostaig, however, there is not room to show any of his really big paintings and the show consists of medium-sized and small oils and a group of watercolours. The college is to be congratulated though on creating an attractive space for his watercolours, while the oils, hanging in a hall with high windows opening onto the Sound of Sleat, do look as though they have come home.

Even in smaller pictures he manages to create wide, abstract places where the mind can wander. In Sound Memory, for instance, bars of misty red and yellow cross a cloudy field of white to suggest, not so much the wide vistas of the sound, as an imaginative space that acknowledges their inspiration. The title of Red Sky II, however, refers directly to the constantly changing skies of the west. Grey Silver Blues, a lovely misty screen of scumbled white over blue, suggests the relationship of his work, always improvised, to the blues and to jazz. He had been a jazz musician at one time and it was always part of his inspiration. The spontaneity of improvisation is even more apparent in his watercolours, a medium he first took up on Skye. Sometimes little more than dashes of ink or colour across the sheet, they are nevertheless both expressive and evocative of the movements of the sky, of the light and of the weather, all of which as he often observed were in constant dynamic flux over Skye and the Sound of Sleat. These works on paper are more than anything reminiscent of Turner. It is as though Schueler had worked his way through abstract expressionism to link up with an older and deeper vision of nature and our place in it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

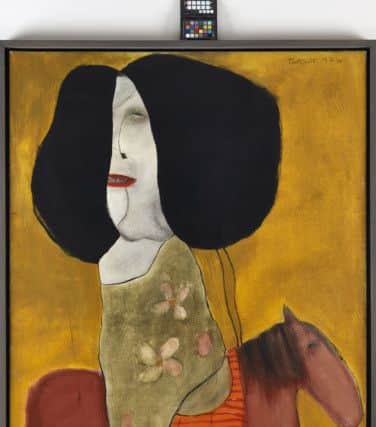

Hide AdIf Schueler laid his demons to rest in the wide skies of the west, in Pat Douthwaite’s work at the Scottish Gallery, hers are right there on the canvas. She portrays her restless, troubled and often disturbing vision of the human figure in an inimitable drawing style, at once fluent and wiry, and makes dramatic use of empty spaces. She was the last protegée of JD Fergusson and Margaret Morris and the exhibition also marks the publication of a biography of her by Guy Peploe.

If a painting by Schueler on your wall might be a source of comfort, or at least an object of contemplation, a work by Douthwaite could never be, though they are undoubtedly both powerful and original. Very different from either, a Scotch Country Fair by Alexander Carse, one of a distinguished group of Scottish pictures in the Fine Art Society’s Signatures of Scottish Art show that includes works by Raeburn, Ramsay, Cadell and others, ought to be on the nation’s walls. Crowded with life and humorous observation, this is not a sophisticated picture, but it is nevertheless a major contribution to the tradition of Scottish painting of ordinary life. It brings together the inspiration of Wilkie, Burns, Robert Fergusson and beyond them Scotland’s historic connection with Holland and with Dutch art.