Art review: Jacqueline Donachie | Duncan Marquiss

In Jacqueline Donachie’s new film installation Hazel two screens are suspended side by side in the darkness. On one we see a succession of five women who sit silently for the camera, occasionally blinking, their thoughts unspoken. On the left are a series of talking heads: women who talk frankly and openly, telling stories of frustration and at times of unfathomable loss. They speak of disability, of changing bodies and of changed lives.

Jacqueline Donachie: Deep in the Heart of Your Brain | Rating: **** | Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuncan Marquiss: Copying Errors | Rating: **** | Dundee Contemporary Arts

The women are pairs of sisters. You watch them and slowly realise how their sometimes startlingly dissimilar appearances disguise the shared characteristics within. Some of the sisters are emotionally close, some not so, but they are all dealing with the devastating knowledge of their difference. The talking sisters have each inherited the gene for myotonic dystrophy, a progressive neuro-muscular disorder. The silent sisters have not. As the film ends another screen flickers into life: two figures walk side by side down a long corridor. Their similarities, they are both tall, rangy, dark-haired and dressed in black, are offset by the differences in their mobility and gait. For the stories in the film mirror Donachie’s own life. This is the story of the artist and her sister.

Deep in the Heart of your Brain, is a show about family, about ageing, about love and lineage, about the best of circumstances and some of the hardest. The title is quote from the musician Patti Smith about the slog of motherhood and family life, about the person and the artist within the fug of everyday exhaustion. If Hazel is a filmed portrait of sisterhood so too are the tall drawings of urban streetlights that hang on the gallery walls, each bearing a familial resemblance to the others. The metal pole that is clad in neon rope that greets you when you enter, is a fleeting memory of the sisters out dancing. The suspended leg of a suit of medieval armour that hangs in the gallery, is both an image of restriction and an injunction never to mistake the bodily casing for the person inside.

Donachie, part of the generation of artists who transformed the Glasgow art scene in the 1990s, has a rich and complex artistic practice. She works in film and public art, has long been involved in social and participatory artworks and recently she powdered the streets of Melbourne and Glasgow with coloured chalk, distributed by meandering cyclists as part of a series of works called Slow Down.

But if she often makes art that is voluble and sociable, this tough, beautiful show is spare but no less eloquent. A low urban box sculpture is made from the powder-coated metal sheets that are used to make wheelchair ramps. An orange handrail runs through the space, making awkward jumps of height and angle, it recalls a route through the city spaces, or the way, Donachie recalls, her father used a washing line to support him as he walked. But it also tells of the mysterious thread of genetics, of family history, of shared endeavour and care.

Difference too, lies at the heart of Duncan Marquiss’s new show Copying Errors, the differences evident in the fossil record and the different stories that scientists might draw from their observations of fact.

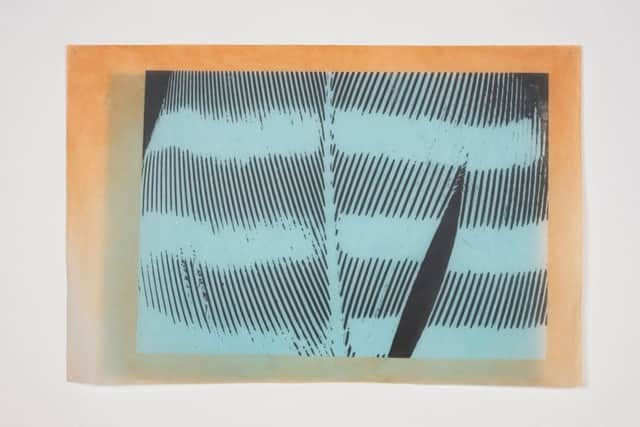

Marquiss, who when he is not making art plays music with the marvellous Phantom Band, has dedicated the main gallery at DCA to a series of drawings, prints and ‘frottages’, the rubbed drawing method beloved of the surrealists and in particular Max Ernst. He is a brilliant draftsman who in much of this work is fighting against his own fluency. These are awkward works, perhaps hard to love at first, but they demonstrate how he pushes himself hard into areas of chance and rhyme, turning studio detritus and even his old clothes into works of art based on contact and texture, uncovering our desire to find the underlying pattern and form. A pair of witty new screenprints on denim feature the patterning of jay feathers and describe the phenomenon whereby the jay’s glorious iridescence is created not by pigment but by the optical effect created by the faceted structure of the bird’s feather.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the show is unmissable because of Evolutionary Jerks & Gradualist Creeps, Marquiss’s wonderful film about evolutionary biology and evolutionary biologists which secured a Margaret Tait Award for artists’ film in 2015 and was premiered at the Glasgow Film Festival this year. The film features two scientists. First there’s the gentle, bearded American palaeontologist Niles Eldredge who, with Stephen Jay Gould, modified the slow creep favoured by Darwinian theory, to suggest that evolutionary change happens in sudden steps. For an iconoclastic scientist Eldredge is a gentle soul, a cornet player and instrument collector, reluctant to make great claims beyond his fields of observation and aware of the dangers of a discourse in which Darwinian metaphors are wielded like blunt and brutalising weapons. In contrast Armand Marie Leroi, the very picture of the charismatic pop professor, has used his scientific chops to apply the methods of evolutionary biology to the music of the Billboard Charts. Marquiss resists the temptation of mocking a grown man who sees the history of musical endeavour as a data set of oohs, ahs and eehs, turning the film into a lovely and nuanced study of innovation and mutation in science and art and a fable about the stories we tell ourselves to create order and pattern where there may, in fact, be none.

• Jacqueline Donachie until 13 Nov; Duncan Marquiss until 3 July