Art Review: Drawing Attention at the Scottish National Gallery | Joyce Gunn Cairns and Alasdair Gray at Sutton Gallery

Drawing Attention: Rare Works on Paper 1400-1900 ****

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Joyce Gunn Cairns and Alasdair Gray ****

Sutton Gallery, Edinburgh

The Scottish National Gallery has a large and very fine collection of drawings, prints and other works on paper. For the last 40 years and more this rich and diverse collection has been housed in the basement extension at the Mound, built when money miraculously became available for Scotland-friendly projects just before the devolution referendum of 1979. In keeping with the politics of the moment this basement also became the dismal home of the national collection of Scottish art. Now, however, the extension is to be rebuilt and greatly enlarged. Running the whole length of the building, it will be the new home for the Scottish collection of paintings and sculpture and the principal entrance to the galleries. This is a welcome if long overdue response to criticism of the shabby way the national collection was dumped in the dingy basement where few people ever saw it. The only anxiety is that although every visitor will now see it, Scottish art will still be separated from the rest as though different and so perhaps implicitly inferior. As almost half the pictures in the collection are Scottish, there should be enough both to create a proud national entrance display and to allow major Scottish pictures to take their place where they belong among those from the rest of the world.

Meanwhile, however, the national collection of drawings will be displaced. It will be housed temporarily at the Dean while its old home is demolished and rebuilt. As a kind of au revoir, a display of drawings has been put into two of the rooms in the basement of the RSA building. Thus we are reminded how rich the collection is in case in its absence we should forget. Meanwhile, the Galleries’ revamped website includes vastly more works on paper than before and as it evolves it will provide a new route into the wealth of the whole collection, including the works on paper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are more than 60 works on view in the RSA in rooms that are much more spacious than the tiny box room that has been used for periodic exhibitions of works on paper hitherto. A miscellany, they range in date from the 15th to the early 20th centuries. They are Scottish, English, French, Italian, German, figure drawings, compositional studies and landscapes, drawings in chalk, ink, pencil and watercolour and in combinations of some or all of these. One thing that is notable reading the labels is that more than a third of this selection come from just two original sources, the William Findlay Watson bequest of 1,400 drawings in 1881 and David Laing’s bequest on a similar scale to the RSA, transferred in part to the NGS in 1910, in the deal which gave the Academy its building.

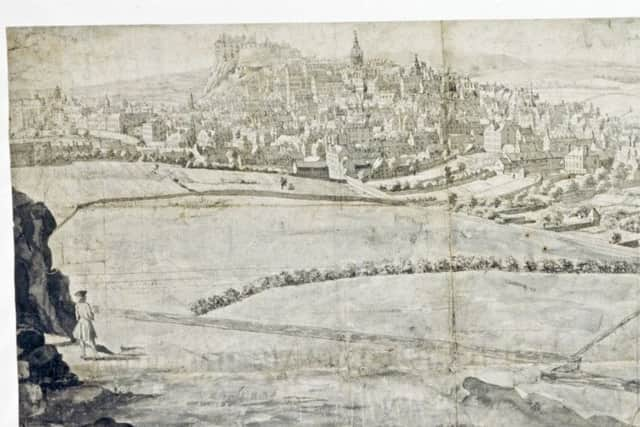

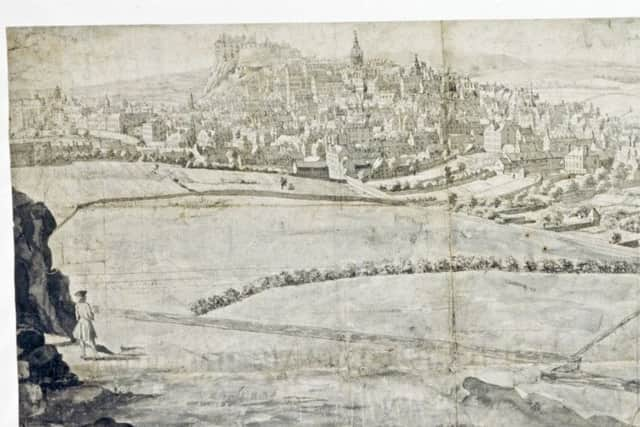

One drawing that will certainly attract attention is attributed to Thomas Sandby. On multiple sheets pasted together, it is a panoramic view of Edinburgh from Salisbury Crags before the roof of Holyrood Abbey collapsed in 1768. It is highly detailed and a fascinating topographical document, but the format and carefully observed perspective also points to the artist’s interest in what was to become the Panorama which Robert Barker claimed to have originated in Edinburgh a few years later.

A drawing of a church interior by Domenicus Rosemale shows interest in similar ideas in Holland a hundred years earlier. It seems distorted, but is actually an attempt at optical perspective: how things would look were we actually inside the picture looking around, not outside looking in. (The great Saenredam church interior in the collection is the same although it is hung too high to demonstrate how this perspective works.)

For sheer beauty of draughtsmanship, Wilkie’s Mary, Queen of Scots and her Infant Son matches drawings by old masters like Guido Reni, or Federico Barocci. The creative energy of Alexander Runciman’s Marriage of Saint Margaret and King Malcolm is unmatched, though a drawing of Oedipus and Antigone by Francois-Xavier, Baron Fabre shows a similar ambition. Runciman’s friend John Brown, who thought painting messy and so only ever drew, is more controlled in a charming pencil portrait of a pensive girl in a fantastic bonnet.

The delicacy of observation in a drawing by Roelandt Savery of a clarty street in the outskirts of Prague is exquisite, but is matched 300 years later by a watercolour of a tree by William Turner of Oxford and a similar study of a beech wood by George Wilson, a little known Scottish painter. Francis Towne’s Edinburgh Castle looks cubist, but was painted in 1811. A drawing of a sea captain by Gainsborough is full of human warmth, while German artist Johann von Leonhardshoff makes his Repentant Magdalene distinctly voluptuous. A large black bull in watercolour by EAWalton dominates one room while one of the smallest drawings is a beautiful study of craters on the moon seen through a telescope by James Nasmyth. The most beautiful of all perhaps is Three Ladies of Fashion by Bessie MacNicol as she evokes the women and their wonderful clothes in delicate veils of colour.

Drawings are also prominent at the Sutton Gallery in a joint show of work by Alasdair Gray and Joyce Gunn Cairns.The two artists make a study in contrasting styles. He draws firmly with a clear and definite line. All his work here is on paper apart from a couple of very early pictures, a still-life and an interior with two figures. Even then his style was definite and thereafter it becomes highly graphic with forms sharply delineated. This is striking when he draws on brown paper as he does in two drawings of nudes, for instance, and an elegant portrait, May in Black Dress on Armchair. She is seated in an armchair and drawn entirely in black line on the rich brown of the paper, but all surrounded by flat blue. There are a number of works here too where he combines poetic text and image to great effect as Blake once did.

In contrast, Joyce Gunn Cairns draws in exactly the opposite way, as though recording through a tangle of lines her search for an elusive reality, something that can never be finally pinned down. Her drawings include strange, ghostly studies of cats, birds and other animals, but her show also includes paintings. These are more resolved, but retain the sense of exploration, as though the images she reaches could only ever be provisional. Several are very impressive, but a strange painting of a woman’s torso, angular as an Egon Schiele nude, but with a bird on her head, either a weird choice of headgear, or a vision of metamorphosis, is outstanding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey have also drawn each other. He draws her with a fluent but controlled line and inscribes the drawing with her name in his characteristic tall script, as though he has caught her likeness and labelled it like a butterfly. She in contrast draws him with a haze of crisscross lines as though such certainty as we can hope for can only be reached after a search through the confusion of experience, and even then is still only transient, and any resolution can only ever be a temporary compromise. Both are very effective. n

*Rare Works on Paper until 3 January; Joyce Gunn Cairns and Alasdair Gray until 28 October