Art review: Bridget Riley: Paintings 1963-2015, Edinburgh

Bridget Riley: Paintings 1963-2015 | Rating: **** | Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Bridget Riley is a dangerous artist. In 1999, I lost track of my husband at the Serpentine Gallery in London when we were visiting their fabulous exhibition of her shattering and disruptive paintings from the 1960s and ’70s. These were the dazzling works, often in black and white, in which surfaces shimmered and flared and lines leapt from hardboard or canvas and into the air in front of the painting. Colour appeared, created by the eye, where none had ever been placed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a blazing summer day. I eventually found my husband prone on the grass outside, white and shivering, shielding his eyes. The visual ferocity of the paintings – their dancing, jittering unsteadiness – had floored him.

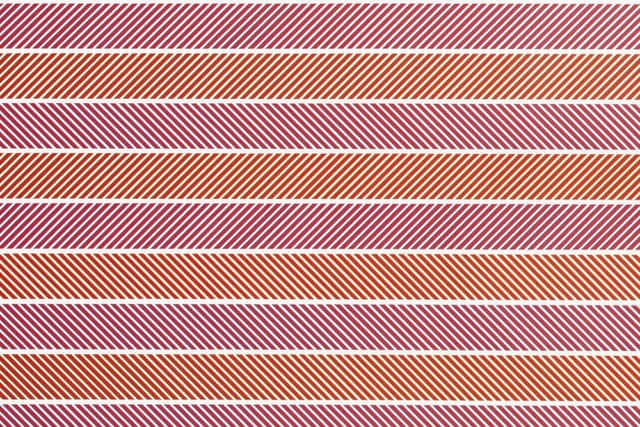

I realise that for some years now I have learned the hard way to defend myself when viewing the early work of an artist who, more than 55 years into her mature career, is surely among the greatest of living painters. A certain steely stance to stabilise my position on the floor, eyes slightly narrowed to defend against the glare. I needed it again at Edinburgh’s Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art this week looking at Burn (1964), a black and white conflagration of triangular forms and Rattle (1973) in which diagonal colour stripes in crimson and cerise batter the senses.

There is a misconception that Riley’s works, which first explored dazzling monochrome effects and later colour and rhythm, are purely optical. But in challenging vision, they remind you that seeing is not neutral. You see not just from the eye but from within the moving, thinking body, with all the weaknesses and complexities that implies. In undermining visual stability, Riley also shakes the mind.

In her early works in emulsion, often on the resistant surface of board, you see the clear evidence of her hand as well as the impact of her clinical intelligence. She once described what might happen in front of the more daring of her early experiments as “repose, disruption, repose” – it is a matter of holding steady and holding your ground.

And hold steady she has. Last month Riley celebrated her 85th birthday. Her early stardom (early for a painter – she was in her early thirties when she broke through after studies at Goldsmiths, personal adversities and artistic frustrations) befuddled many commentators. One critic found the inexorable discipline of her work surprising in a woman and compared it to embroidery. Famously, as a fine-looking woman in swinging London, she was photographed as if she was Mary Quant rather than the figures she might have wanted to emulate: the experimental post-impressionist artist Geroge Seurat, the playful yet theoretically brilliant Paul Klee. But she settled down for the long haul in the studio, maintaining discipline, experimentation and rigour throughout her long career.

Recent years have seen a number of major exhibitions of her work, including that Serpentine show, a marvellous Tate Retrospective in 2003 and her largest-ever career survey in Paris in 2008. It’s on an altogether tinier scale that the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art has dedicated two upstairs rooms to paintings spanning six decades: the show is really a pocket guide to her work.

But scale doesn’t matter here when strength is everything: sharp, succinct, bracing and yes, at times dazzling, this small selection of paintings, drawing from a private collection, is canny enough to admit that it is a display rather than an exhibition, but it is a marvellous display nevertheless.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

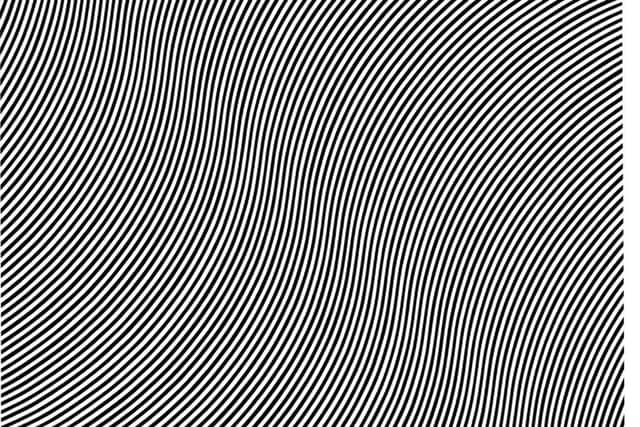

Hide AdIn 1974, shortly after hosting it in a touring exhibition, the gallery acquired Over, a signature painting from 1966 in the form of a small square in which undulating parallel curves seem to shift in direction in depth and which anticipates the colour stripe paintings to follow. It has early companions on display here, including Static, a series of dots that slip between perfect circles and misshapen ellipses.

Riley’s first optical works came out of crisis, personal and artistic. She was attempting to make all-black paintings when she began the black and white works that brought her fame. After that came stripes and later complex (though occasionally unlovely) colour works evoking curves and colour sensations. What united all these works was the complex interaction of discipline and freedom, authorial control and viewer subjectivity, and the open-ended question of where the artist’s work ends and the beholder’s eye begins.

The display ends with Clair Obscur, a grand acrylic of more than 2mx4m in black and white, a return to old monochrome values that began just two years ago.

The catalogue makes much of the novelty of showing this new monochrome work against the old. Clair Obscur recalls key paintings from the Sixties such as Tremor (1962), in which black and white triangles form an unstable field of troughs and furrows. While Tremor might recall a sharp surprise like a slap in the face, Clair Obscur pummels you more gently. Larger than you, it fills your whole field of vision and appears as a series of minor associated movements. Triangles morph into lozenges and pyramids, pyramids coalesce into waves and stripes.

I’m always a little hesitant about the kind of museum display that serves a collector’s desire to anchor the newly made or newly acquired in the unpredictable ebb and flow of art history. And there is something triumphant (perhaps even triumphalist) in this late work in terms of size and material (acrylic on polyester). Yet, as this little show reminds us, Riley is indeed an artist who has triumphed.

• Until 16 April 2017