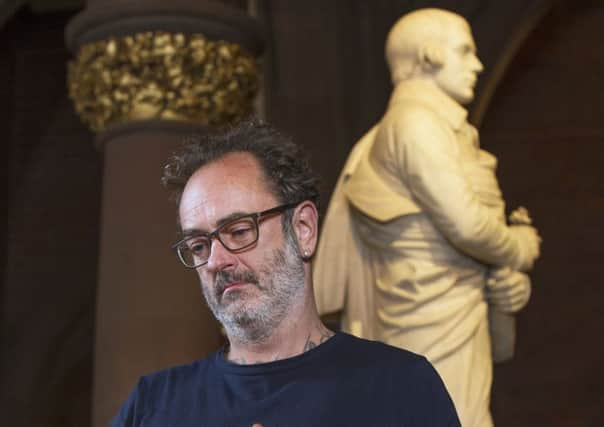

Art interview: Douglas Gordon '“ '˜I love the Flaxman sculpture of Burns, but I had to break it'

I’m sitting in the (closed) cafe of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, waiting for Douglas Gordon. Of the generation of artists who stamped the name of Glasgow on the contemporary art map of the world, he is the most famous, the most elusive, the most rock’n’roll, last seen in Berlin, or Sydney, or was it New York? As the minutes tick away, I wonder whether that mystique is partly achieved by not turning up for interviews.

Gordon is here to install a major commission, a response to the John Flaxman statue of Robert Burns, in the Portrait Gallery’s Great Hall. But he isn’t in the building, and hasn’t been since he went for “lunch” some hours ago. It’s now 5:15pm.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother half hour passes. I’m ushered into the Great Hall where a weary-looking Douglas Gordon is moving around the pieces of his sculpture. The work, which goes on public display from today, is an exact replica of Flaxman’s sculpture but in black marble, smashed into pieces which are arranged on the floor. He frowns at the current arrangement, rubs his face with his hands, steers me towards the door. “Come and have a cigarette,” he says, adding as an afterthought: “Do you smoke?” He looks preoccupied; his shoe laces are undone. Suddenly, he turns and looks me straight in the eye: “Have you ever laid a body to rest?”

It’s a bit like that, he says, with him and Burns. We stand in the lee of the Portrait Gallery wall while he smokes one cigarette, then another. The early evening traffic roars by. “When people say ‘What’s the icon of Scotland?’ for me, it’s Burns. And I break him.” He pauses, laughs. “You should speak to my therapist.”

Gordon was given a free hand by curators to respond to any work in the Portrait Gallery collection. He chose Burns. “I could have done something really nasty with Queen Victoria,” he guffaws, briefly. He is, by turns, jocular, confiding and profoundly serious. Burns is important to him. His father shares a birthday with the bard. He recited Scots poetry at school for his Burns Society Certificate. “I still have it. It’s a very emotional thing for me, and I love the Flaxman sculpture.” Briefly, he looks very sad. “But I had to break it.”

The new work is called Black Burns. Gordon’s work is full of doubling, alter-egos and dopplegangers: for every Jekyll, a Hyde; for every white marble figure, a black one. But the broken pieces make me think of iconoclasm, jubilant crowds pulling down statues of Saddam Hussein. “Well, I’m trying to say not ‘breaking’, I’m trying to say ‘opening’. I think all men – mankind – should be opened. It’s kind of what he did. Poets do that. And songwriters. They open themselves. I try to say to my kids (he has a daughter in Berlin and a son in New York from previous relationships): be open, be open, be open.”

Like the poems Jackie Kay has written for the publication that accompanies the work: “If you read those poems, they’ll break you.” Or the day Sorley MacLean came to the art school and sung in Gaelic. Or the day Joe Strummer turned up in a bar in New York and sang the Cuban folk song Guantanamera to him and Damien Hirst. “It’s a kind of destruction, because it opens your audience. The mother of my daughter is a soprano. Now, when she f***ing sings, it really pierces you.

“The monument to him, the white sculpture, it doesn’t actually represent the labour and the intention and the beauty of writing, and I wanted to [do that]. He was a ploughman. I’ve just started to shoot a film up in Glen Etive – it’s so beautiful and bleak and desolate, and the midges…” He shudders. “The cottage where I was shooting had a plough outside. Imagine actually ploughing, with a horse, and you’re getting bitten to death, and you’re thinking about a love song: ‘Aye fond kiss, and then we sever…’ It’s so moving. I wish I could do that. It’s a self portrait of the desire to be something I just can’t.”

It’s a humbling admission from an artist at the top of his game. Two decades ago, Gordon won the Turner Prize for 24 Hour Psycho – Hitchcock’s movie slowed down, frame by frame, to last 24 hours. It is the moment many still recall as the birth of the so-called “Glasgow miracle” which has seen artists based in the city win an impressive string of awards. Other prizes followed for Gordon: the Premio 2000 at the Venice Biennale in 1997 and the Hugo Boss Prize in 1998. He found himself under commission for some of the top galleries and museums in the world. His work combined a conceptual rigour with an ability to connect with people, drawing on a common cultural language: movies, books, football. He is the master of the beautifully encapsulated idea you wished you’d had yourself, but never would have.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland is written through him – literally: he has a tattoo on his arm saying “We never said no” – yet he hasn’t lived here since leaving art school. His studio is in Berlin, his girlfriend in Paris, yet he manages to sound like he has never left. “My ex-partner once said, ‘Every kilometre you get nearer to Scotland, you speed up and you’re illegible [sic] by the time you arrive’. Well, aye, I am for you, but not for the taxi driver.” A piper somewhere starts playing A Scottish Soldier and he stops talking for a minute to sing along.

He’s delighted that the next room in the Portrait Gallery houses work by his old art school contemporary, Graham Fagen, his work inspired by Burns’ ‘The Slave’s Lament’ made for the Venice Biennale in 2015. They’ve known each other since they both enrolled in Glasgow School of Art in 1984. It was a creative time, he says. Everyone was in a band, or played football, or both. “That’s why Jim Lambie and Nathan Coley and Roddy Buchanan and Richard Wright are doing what they do. Jonathan Monk, David Shrigley, Ross Sinclair, we all played football together. And Martin Boyce, although he wasn’t the best football player ever.” He laughs.

“I remember we were in the life drawing class. It was the usual thing, naked girl, and Graham leans over and says to me: ‘The Clash are here, they’re playing an acoustic set down at the Rock Garden.’ I can remember the sound of the bits of charcoal dropping to the floor.”

Early on, he understood that creativity for him was fuelled by being around other people. “I think one of the great things that I learned from my parents, my brother and sister and my teachers was to go out and… I don’t believe in the ivory tower. I picked up on conversations, films, images from other people in bars, on planes, on a train. I got everything from other people. I’m a professor at an art school in Frankfurt, and I say to my students: pick up everything, throw nothing away. There’s no such thing as litter. To be literate, you have to have litter!” It’s the same today. In recent years, his collaborators have included musician Rufus Wainwright, classical pianist Helen Grimaud, theatre director John Tiffany and fashion designer Agnes B.

And is this work, in a way, a collaboration with Burns? I ask him what he admires most about the ploughman poet. “He had his feet on the ground. And he was seduced and abandoned. And the great thing for me is that three times he chose not to go to the West Indies. I think Burns is a great example of choosing not.” He grins. “He’s a punk. He’s a f***ing punk!”

Douglas Gordon: Black Burns is at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, until 29 October