Album reviews: Paolo Nutini | Neil Young with Crazy Horse | Laura Veirs

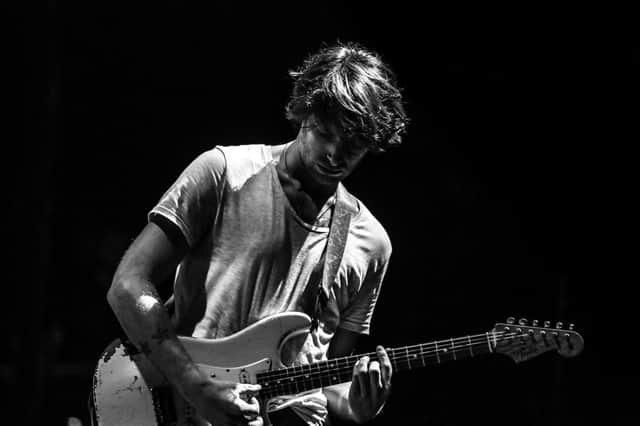

Paolo Nutini: Last Night in the Bittersweet (Atlantic Records) ****

Neil Young with Crazy Horse: Toast (Reprise Records) ****

Laura Veirs: Found Light (Bella Union) ****

Eight years is a long time in pop music but Paolo Nutini can afford to make us wait for the follow-up to Caustic Love, his brilliant third album which established him as one of Scotland’s most respected musicians, while the success of his first two albums, These Streets and Sunny Side Up, gave him the latitude to steadily grow as an artistic force to this point of devil-may-care maturity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLast Night in the Bittersweet is a beast of a creation, with 16 tracks spanning over 70 minutes. But it is easy on the ear, thoughtful and meditative in places, giving equal space to some of his prettiest songs to date and some of his stormiest jams.

It begins with the almost spiritual invocation of Afterneath, a slow-burn cocktail of burnished guitar, springy bassline, motorik drums, sampled spoken word and Nutini himself as a Caledonian beat poet. But we’re here for the singing voice, and he takes his time on the soulful blues of Radio and the gentle but sure touch of Through the Echoes, a gorgeous seduction in the vein of Candy.

Back in the mid-2000s, Nutini was personally signed by Atlantic Records legendary founder Ahmet Ertegun, who knew an old soul when he heard one. Almost two decades on, Nutini continues to make good on that promise with classic influences galore – not just Lose It’s Krautrock jam with a blues twist or the McCartneyesque piano ballad Julianne but the smart New Wave pop of Petrified in Love and the tender acoustic R&B ballad Everywhere, which builds naturally with a martial beat, twanging guitar and soulful brass before heading into the home strait with a great Celtic soul guitar break.

Children of the Stars goes full Stevie Nicks hippy rock with luxurious harmonic backing chorus and a Lindsay Buckingham-style guitar wrangle to boot, while there is even a bit of a Chain-like blowout on the peppy Desperation. Closer to home, the breezy Shine A Light creates a sense of scale like a light touch Simple Minds, while the spirit of his fellow Paisley buddy Gerry Rafferty is all over the folk intimacy of Writer.

He saves a gem for the closing stages, delivering a plaintive, vulnerable vocal on the prog jazz rock intersection of Take Me Take Mine which, like the rest of the album, simultaneously breaks new ground for Nutini while springing from his natural soul.

Some people tidied their sock drawer during lockdown; Neil Young sifted through his ample archives and decided that the time was right to release a fabled 2001 recording made with his band Crazy Horse at San Francisco’s Toast Studios, but shelved until now because Young felt it was so sad he couldn’t put it out.

Toast is a series of studies of individuals for whom “everything is going south” from the redundant logger grappling with his fading faith on Timberline to the bittersweet break-up of Quit, all executed with greater care than his more recent bish-bash-bosh adventures in lo-fi.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ten-minute Gateway of Love is almost blithe in spirit, especially in comparison with the following disconsolate How Ya Doin? featuring Young’s gently weeping guitar and comforting female backing vocals, while the closing Boom Boom Boom is a typical leisurely acidic meander, with atypical warm brass fanfare to close.

Since splitting from her producer husband, Portland-based alt.folk singer Laura Veirs has been building back her musical confidence with new collaborators. Found Light is a subtly stylised album of simplicity and space which, aside from a couple of grungier indie numbers, layers up her voice and guitar into chiming indie folk canons, garnished at points with jazzy woodwind and plaintive fiddles to cleansing effect.

CLASSICAL

Xiaogang Ye: Sichuan Image (BIS) ***

This is film music, literally, but also in the purely stylised sense that it is atmospheric, unchallenging, conceived in easily edible soundbites, and unquestionably pleasing. It features the RSNO – joined by a series of traditional Chinese musicians and pianist Noriko Ogawa under conductor José Serebrier – in two works by Shanghai-born Xiaogang Ye. There are 29 “images” in Sichuan Image, written as a sequence of succinct musical postcards to accompany a filmed travelogue of this Western Chinese province. Their strength is you don’t have to be there to sense the shifting vistas, the rivers and mountains. Ye’s music, a personalised traditionalism warmly perceived in delicately shaded performances, is honest and emotive. Concerto of Life, a five-movement suite based on a score for a feature film by the same name, is no less palatable, Ogawa’s gently effusive pianism bringing some added lustre to the mix. Tasteful, inoffensive and listenable. Ken Walton

JAZZ

John Scofield: John Scofield (ECM) ****

With the help of an electronic looper, the mighty John Scofield ranges fondly across the genres which have informed his music over five decades, from bebop to country and rock and roll. Shaping every note over judiciously layered accompaniments, his own compositions include the snappy Elder Dance and edgy drive of Trance du Jour, contrasting with the languidly sweet Mrs Scofield’s Waltz. Cover choices are engagingly eclectic, including jazz favourites such as the gentle swing of It Could Happen to You and the slickly chorded There Never Will Be Another You. There’s the Bo Diddley pulse of Not Fade Away, a lovingly articulated Hank Williams weepy, You Win Again, while beautiful deliberations on Danny Boy, of all things, morph from a straight rendition into a startling, Indo-blues buzz. Despite the electronics, there’s a fine intimacy to it all: you could be there in the room with him. Jim Gilchrist