A new display of maps at Edinburgh Castle follows the story of their vital role in warfare

Maps have long played a vital role in warfare, aiding everything from strategy and planning to escape and evasion. During the Second World War, an astonishing 342 million maps were produced by the British Armed Forces alone, alongside over 36 million photographs.

But what happened to these maps after the war ended and their original use became redundant? A new display at the National War Museum in Edinburgh Castle explores the purpose, importance and personal significance of these military maps during the Second World War and in the years which followed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaps: Memories of the Second World War, which opens tomorrow (9 March), reveals how these maps and photographs evolved from their original use. No longer a vital tool in directing troops or devising a plan for escape, they became mementos and memories, kept alongside medals, photographs and other memorabilia.

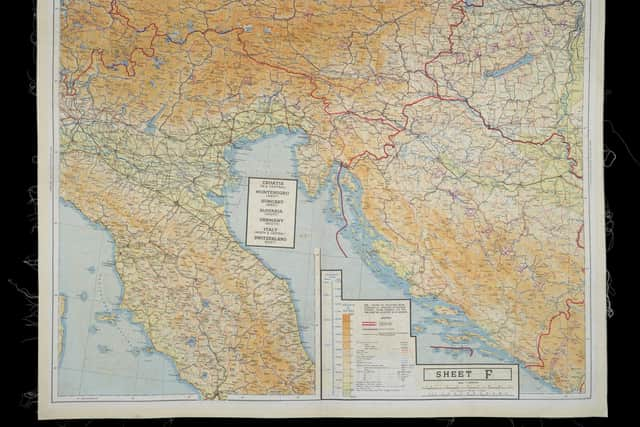

The display presents different types of maps produced during the Second World War – from the official Ordnance Survey to the unofficial newspaper reproduction – to uncover the stories of individuals who created, used and retained these mementos of warfare.

The display is inspired by a painting, 'Major Robert W. Cairns MBE, TD, MA Father's Memorabilia, North West Europe', (1995), by Joyce W. Cairns PPRSA. The artist’s father, Major Robert W. Cairns MBE, served in various posts and locations during the war. From 1943, he was responsible for organising the travel network for the movement of troops and supplies across the inadequate and congested roads of Northern Europe as Assistant Provost Marshal (Military Police) of the 3rd British Infantry Division in Europe. Despite suffering heavy losses, his division was involved in the final assault on Bremen, Germany.

The memorabilia he kept, including maps and photographs, had been stored for many years in a battered suitcase, and many years later his daughter grouped and composed them chronologically and created a pair of paintings to record his role in the war. Some of that memorabilia will be on display alongside one of those paintings.Maps: Memories of the Second World War explores the purpose of a map as much more than just a physical, functional object or tool to find your way, and reveals the personal stories of some of the people who kept these maps as a memory of a personal journey.

While most maps were made of paper, a rather unusual object also featured in the display reveals the ingenuity behind their development. It is a silk dress, made from escape and evade maps used during the Second World War, on loan from Worthing Museum and Art Gallery. Maps made of silk or rayon were issued to pilots and members of the Special Forces to be used in the event that they were shot down, trapped behind enemy lines and needed to escape.

Christopher Clayton Hutton, an inventor and MI9 British Army Officer, came up with the idea of using silk for maps because it’s waterproof, quiet to open and easy to hide or sew in clothing. When, in the era of post-war rationing, the maps no longer served their original purpose, this valuable material was used to make clothing.MI9 (British Military Intelligence) employed Hutton alongside former magician Jasper Maskelyne to devise ingenious ways to smuggle maps, compasses, money and fake documentation into Prisoner of War camps. Working with firms such as John Waddington & Co, the maker of Monopoly, items were hidden in board games, playing cards and gramophone records. MI9 delivered parcels through bogus charities such as the 'Prisoners Leisure Hours Fund' with them hidden inside.

Edinburgh-based cartography firm John Bartholomew & Son Ltd supplied paper copies and printing plates of their small-scale world maps to be used for the MI9 ‘escape and evasion’ maps. They adopted new map projections designed to suit new mapping needs, for example, maps for air travel.Maps were not only used in the field of war but were also a way in which the government could boost morale back home. The basic use of a map as a means of fact, creates a perception of it being a neutral and trustworthy source of information, which made them a vehicle for persuasion and propaganda.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor this reason, government ministries would use maps in posters, leaflets, public information films and newspapers in an attempt to convey successes and boost morale. On display are Daily Express war maps from 1944, which came with a sheet of stick-on arrows to track the progress of the war. Unlike functional maps, these examples were created by commercial artists and included the use of bright colours and suggestive symbols, to reinforce common messaging.

The urgency of the war, along with the advent of aviation, created a demand for maps which differed from their traditional form. Through advancements in aviation and photographic technology, Photographic Reconnaissance units in the British, US and Commonwealth Air Forces produced millions of images, providing vital intelligence for the Allied war effort. The Unit’s purpose was to provide the most up-to-date critical intelligence which could then be used strategically to plan Allied actions in the war. As soon as these aerial missions were completed, the film would quickly be developed.

A key organisation behind the rapid interpretation of these images was the Central Interpretation Unit based at RAF Medmenham, where thousands of photo interpreters would work to analyse the data. By 1945, the base was handling around 25,000 negatives and 60,000 prints daily while the RAF’s reconnaissance flights were generating up to 50,000 images a day.

A key instrument in creating maps included using two aerial photographs taken short distances apart and viewed together, thus creating a 3D view of the landscape below. Using a stereoscope, photographic interpreters were able to identify secret Nazi weapon development facilities and monitor the movement of German Naval vessels. Visitors to the Museum will see examples of aerial photography as well as a stereoscope used to view images of the landscape below in 3D.

While the First World War saw the increased use and production of military cartography, the Second World War expanded its use even further. Despite this, the instruments and equipment used to survey the landscape had not changed much in the intervening years. Many areas of the world were unmapped or poorly mapped and as such the skills of Field Survey Companies were in high demand. As a result, staff, with the support of local civilian surveying teams and from colonial survey organisations such as the Survey of India and Survey of Egypt, made a significant contribution to the surveying of Africa and Asia.

Maps, reconnaissance, and the systematic recording and processing of geographical information informed both Allied and enemy action. They were vital bits of kit so it’s no surprise that they often form part of a collection relating to an individual’s experience of war.

As with many of those who have had personal experience of warfare, Joyce Cairns’ father did not speak casually of that period of his life. Following his death in 1972, she sought to learn more about his experiences of the war, and “ventured to unlock the Pandora's Box" of his keepsakes. While Major Cairns left no written account of this time, those tangible mementoes, ranging from insignias and uniforms to photographs and maps, act as a powerful marker; something to say, ‘I was here’.

Maps: Memories of the Second World War is on display from tomorrow until 25 January 2026 at the National War Museum in Edinburgh Castle. Visit www.nms.ac.uk/war for details.