A history of Edinburgh's hidden vaults and tunnels

We take a close look at eight of Edinburgh’s hidden tunnels and vaults.

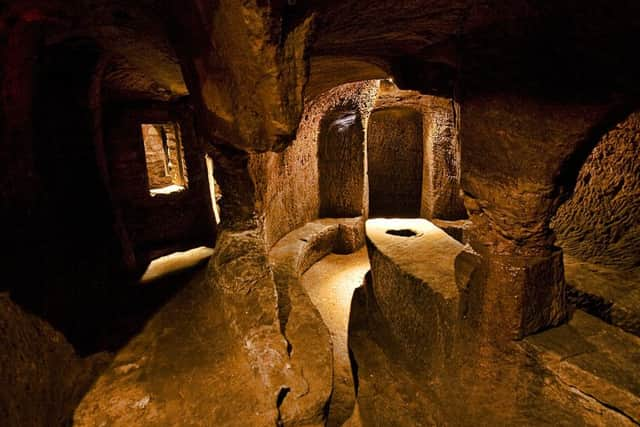

South Bridge Vaults

Spanning the Cowgate valley south of Edinburgh’s High Street is the appropriately-named South Bridge, just one of several bridges to be found in and around the Old Town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConstructed from 1785 onwards, the bridge consists of 19 arches, only one of which, the Cowgate arch, is visible, the other 18 are all hidden by buildings on either side.

Between each of these 18 arches exists a system of vaults. Those at the lowest level were originally used to house taverns, cobblers, a distillery and other trades. These business were eventually abandoned due to the lack of light and sanitation.

However, despite the appalling conditions there is evidence that they were then used for a time as the very poorest housing. At some point in the 19th century, the vaults were filled in with rubble to discourage their use for nefarious purposes.

Businessman and former Scottish rugby internationalist, Norrie Rowan, is credited with rediscovering the vaults in the 1980s.

Norrie spent a number of tireless years excavating tonnes of rubble by hand from the labyrinth of spaces and has since opened The Caves and The Rowantree bar venues in part of the vaults to the south of the Cowgate.

In 1989, Norrie even helped Romanian rugby player, Cristian Raducanu, elude the Romanian ‘Securitate’ secret police by using a trapdoor in the Tron Tavern which led to the vaults and allowed Raducanu to emerge several hundred yards away from the premises.

Another section of the South Bridge vaults off Niddry Street is preserved and open for guided ghost tours; the dimly-lit 18th century cellars and low ceilings creating the perfect spooky environment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe old bridge, meanwhile, continues to serve the city well, having never been built with today’s heavy road traffic in mind.

Mary King’s Close

Edinburgh has the reputation of being one of the most haunted places in the world, but if you want to learn about the city’s hidden history you could do worse than book a visit to the Real Mary King’s Close, where you can learn the truth behind the myths.

Situated opposite St Giles’ Kirk, the close was densely-inhabited until the middle of the 18th century when the old tenements were demolished and the great bulk of the City Chambers built on top of their ancient foundations. Wandering around what remains, it’s fascinating is that large sections of these old dwellings have been left intact.

For years, the hidden closes of old town Edinburgh have been shrouded in mysteries, with blood-curdling tales of ghosts, murders and of plague victims being walled up and left to die. Now, new research and archaeology evidence have revealed a truer story, rooted in fact which is more fascinating than any fiction. The Real Mary King’s Close tells the real stories of the people who lived on Edinburgh’s closes through over 600 years of history. You can meet the merchant burgess Mary King herself, the Craig family who lived (and died) on the Close when the plague was at its peak, and the Chesney’s who were the last family to leave the Close in the early 1900s.

The Real Mary King’s Close opened in the spring of 2003 and has attracted over two and a half million visitors to date, welcoming guests from all over the world on a daily basis.

Gilmerton Cove

A network of secret underground tunnels is one of the last things you’d expect to find lurking beneath the streets of a typical suburb, but Edinburgh isn’t your typical city.

Drum Street in Gilmerton is home to the ‘subterranean chambers of a remarkable cave’ thought to have been inhabited up to 300 years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cave is about ten feet below the surface and is reached by a flight of twelve steps which lead into a 40-feet long passage with an unusual series of rooms and passages on each side. At its far end, the main passage curves to the right and there is an entrance to a narrow tunnel about 3 feet high, compared with the main parts of the cave which have a ceiling height of around 6 feet.

One theory is that the tunnel at one time provided a link to Craigmillar Castle which is some distance away. In 1897, F R Coles, Assistant Keeper of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, investigated the cave and considered that ‘the method of cutting the stone pointed to an origin’ dating from well before the 18th century and the substantial work involved in excavating the cave must’ve taken decades. It’s still not known when the cove was constructed, who was responsible and for what purpose.

Gilmerton Cove is now among Edinburgh’s most highly rated tourist attractions since it reopened in 2003. Some even claim the passages to be haunted.

Barnton Quarry’s ‘top secret’ bunker

Buried 100 feet beneath an innocuous-looking, graffiti-laden structure on Corstorphine Hill lies a chilling remnant of the Cold War: a secret bunker equipped to house hundreds of state and military officials in the event of nuclear fallout.

Constructed in 1952 in the hollow of the old Barton Quarry, the bunker, the only surviving one of its type in the UK, was used as the Sector Operations Centre for the Caledonian Sector, receiving information from radar stations across Scotland.

The little-known site lay derelict for decades after the end of the War and suffered badly in the 1990s when the entire complex was gutted out by a huge fire.

In recent years, the bunker has been undergoing an extensive multi-million pound restoration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is expected that the former top secret bunker will be open for public visits at some point in the next year.

Waverley Vaults

Waverley vaults were built during a £1.5 million redevelopment and expansion of Waverley Station by the North British Railway Company in the mid-1890s.

Scores of old buildings and a cooperage were demolished and the site excavated as engineers raised Waverley Station seveal metres higher than it had been previously.

Much of the station effectively sits above these vaults.

The vaults were originally accessible from New Street, and if you go down there today you can still see one of the remaining entrance arches, albeit blocked up with expanding concrete. Half of the vaults were lost during the

A trawl through The Scotsman archives offers up scant mention of the vaults, though a number of advertisements from the 1920s show that the public were able to rent some of the many rooms for storage use.

The vaults continued to be used for storage well into the 1980s, but today they have been largely forgotten about.

Scotland Street Tunnel

Many New Town residents are blissfully unaware of the astonishing feat of Victorian engineering that hides just metres beneath the cobbles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConstruction on the Scotland Street Tunnel began during the early 1840s. It would help to forge a direct link from Canal Street Station (later renamed Waverley Station) to Granton and beyond.

Despite the huge amount of money and effort to complete it, Scotland Street Tunnel was abandoned in 1868 after only 21 years of operation.

Since it closed, the tunnel has been used for everything from mushroom cultivation to storing automobiles. During WWII it was even used as Edinburgh’s ‘biggest and safest’ air raid shelter, the evidence of which is still visible down there today.

Any lingering hopes of the tunnel ever fully-reopening were dealt a significant blow in 1983 when the southern portal linking the tunnel to Waverley Station was demolished during the construction of the new Waverley Market.

A narrow ventilation pipe is now the only visible indication of its existence at its southern end. The northern portal is extant, albeit fenced off, and can still be viewed today close to the entrance of George V Park.

Across the park, a little further north along the old line to Trinity, the much shorter Rodney Street Tunnel has recently been opened up as a pedestrian and cycle path.

Today Scotland Street Tunnel has become a curious and largely-forgotten railway relic, but its story is fascinating nonetheless.

The Crawley Tunnel

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of Edinburgh’s lesser known hidden passageways is the Crawley Tunnel. Built around 1821 at the same time as Glencourse Reservoir, the tunnel is actually an aqueduct and runs for about a mile from The Meadows all the way to the foot of The Mound where it meets Princes Street.

The tunnel had been mostly forgotten about when workers rediscovered it in the late 1950s while removing Edinburgh’s old tram lines. This ‘rediscovered’ section was subsequently filled in, though it’s understood that the majority of the tunnel lies intact. Further work to shore up the Crawley Tunnel took place in 2013 when Edinburgh’s tram system was in the process of being brought back.

At the same time, a network of similar tunnels was discovered at the west end of Princes Street at Lothian Road. It is also rumoured that another section of the Crawley Tunnel extends towards Scotland Street.

Innocent Railway Tunnel

Built to serve a carbon-starved capital city, it was Edinburgh’s earliest railway, and boasted the nation’s first railway tunnel to boot.

The Innocent line, was a horse-drawn railway line connecting St Leonard’s and Dalkeith.

Completed in 1831, it was Edinburgh’s debut railway, and its tunnel is one of the oldest in the United Kingdom.

The St Leonard’s coal depot entrance to the Innocent Railway tunnel. The line ceased carrying rail traffic in 1968 following the closure of the coal depot at St Leonard’s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1994, a long section of the Innocent Railway running between St Leonard’s and Brunstane became part of National Cycle Network’s Route 1 which runs from Dover to the Shetland Isles.

The resurfaced route is used by several hundred pedestrians and cyclists every single day.